SDC Rewards Member

Upgrade yours now

The ‘Forgettables’: 5 Australian Prime Ministers You May Not Know Much About

The idea of a “forgotten prime minister” may seem laughable. For Australian historians, it is the governed rather than the governors who need rescuing “from the enormous condescension of posterity” as the English historian E. P. Thompson famously put it.

Our First Nations histories especially were for too long silenced and concealed in what the anthropologist Bill Stanner called a “cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale”.

Prime ministers, on the other hand, are stitched into the tapestry of national history thanks to extensive newspaper coverage, the dogged pursuits of political biographers, and the quest of archivists and librarians to collect their personal papers. Deceased leaders’ names adorn buildings and streets, federal electorates, and dedicated research centres, and in Harold Holt’s case, a memorial swimming pool.

But some, of course, are better known than others. So which prime ministers, if any, can be considered “forgotten” by contemporary Australia? And what does that act of forgetting reveal about our political culture? Commemorative rituals and opinion surveys suggest that some have very much receded from memory.

Here are a few prime ministers who deserve to be a little better known.

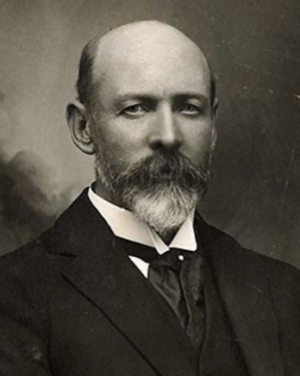

Edmund Barton 1901-03

Barton was a hugely significant figure in his day. A leading advocate of federation, he was summoned by the Governor-General Lord Hopetoun (after a false start) to form the first Commonwealth government.

Between 1901 and 1903, Barton’s government, with the dynamic Alfred Deakin as its attorney-general, established some of the national institutions we now take for granted, such as the public service and the High Court. Barton and Deakin’s deeply racial vision of a White Australia was also enacted in legislation in these years.

Australia’s first prime minister (known to detractors as Tosspot Toby) helped to establish the machinery of federal government out of nothing. But this earned him no special place in Australian collective memory. Resigning in 1903, he spent the remainder of his life as a reticent statesman and High Court judge.

George Reid 1904-05

George Reid, a political enemy of Barton’s, held office from 1904-05. Museum of Australian Democracy

Reid was a political opponent of Barton’s. The defining issue of the early Commonwealth was tariff policy, and all other matters – industrial development, employment, and individual liberty – were refracted through the “tariff question”. Reid, a former New South Wales premier who had earned the moniker “Yes-No Reid” for his prevarications during the earlier federation debates, was a devout advocate for and leader of the Free Trade movement.

Reid was summoned to form a government in August 1904. Hamstrung by his lack of a parliamentary majority, he remarkably passed the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. This was core business for the early Commonwealth, and two previous ministries had failed to secure it. But Reid’s attempts to settle the tariff question with Deakin’s Protectionists failed, and his ministry was defeated in parliament in July 1905.

Joseph Cook 1913-14

Joseph Cook, together with Reid, was instrumental in establishing the two-party system that continues today. National Archives of Australia

Out of office, Reid and his Free Trade colleague Joseph Cook played a crucial role in making the two-party system that endures today. Whatever their differences with Deakin and the protectionists, Reid and Cook (himself a former Labor MP in New South Wales) saw the rising Australian Labor Party as the real enemy.

Reid travelled the country establishing anti-socialist leagues and building the groundwork for a united anti-Labor Party. When the tariff schedule was finally settled in 1908, and the mutual animosity between Deakin and Reid seemed the only barrier to a Liberal fusion, the latter sacrificed himself and resigned so that the former could join forces with Cook on his own terms.

In 1913, Cook led the new Commonwealth Liberal Party to a federal election, winning by the narrowest of margins. He oversaw the opening weeks of the Great War the following year, committing 20,000 Australian troops and the Australian Navy to Britain, but soon lost power in Australia’s first double dissolution election.

Stanley Melbourne Bruce 1923-29

After the war, the task of national leadership fell to Stanley Bruce, a young businessman and ex-serviceman from Melbourne. In 1923, as leader of the non-Labor forces (now reconstituted as the Nationalist Party), Bruce formed government with Earle Page’s Country Party (forerunner of today’s rural National Party). In doing so, Frank Bongiorno has recently explained, Bruce and Page ‘inaugurated the Coalition tradition on the conservative side of Australian federal politics’.

Stanley Melbourne Bruce (pictured with his wife Ethel) had the task of leading the country after the first world war. National Archives of Australia

Bruce’s government was ambitious for Australia in the “roaring ‘20s”. He envisioned a future underscored by British migrants, British money and imperial markets. In power for six years, he presided over the creation of the Loans Council and the federal parliament’s move from Melbourne to Canberra in 1927.

But like others before him, he came unstuck on the issue of centralised arbitration. His attempt to abolish the federal arbitration court (with a view to restraining wage growth) saw his government defeated and his own seat lost in the 1929 election.

Arthur Fadden 1941

Arthur Fadden was chosen to lead his party after Robert Menzies resigned. National Archives of Australia

In the early 1930s, conservatives once again reorganised in the form of the United Australia Party, and dominated politics for the ensuing decade. But by 1941, after two years of wartime leadership, the young leader Robert Menzies appeared to falter. His colleagues disliked his brisk manner and the public lacked confidence in his government’s war efforts. A hung parliament after the 1940 election, in which two Independents held the balance, confirmed this. With his position untenable, Menzies resigned in August 1941 and the coalition unanimously chose Fadden, the Country Party leader, to replace him.

“Affable Artie” was a widely respected figure and apparently the only one who could hold together a decade-old government too consumed by infighting to meet the demands of the moment. His premiership lasted just 40 days, at which point the Independents offered John Curtin and Labor their support. The sole Country Party leader to become prime minister on a non-caretaker basis, Fadden was one of a small handful of men to lead the nation in a global war.

Australia and Its Forgettables

Why is it that these five prime ministers are largely absent from national memory? Four factors seem particularly significant.First, contemporary Australian political discourse offers only a shallow sense of history. Political reporting rarely reaches for historical depth, and when it does, the second world war tends to be the outer limit.

Moreover, when Australians are asked to rank their prime ministers and select a “best PM”, they rarely reach beyond living memory.

The federation generation, overshadowed by the first world war, fare especially poorly. In the 1990s, with the centenary of federation fast approaching, surveys revealed that Australians knew less about its federal founders than they did about America’s 'founding fathers’. What kind of country, the civics experts implored, could forget the name of its first prime minister? Tosspot Toby was no match for Simpson and his donkey.

Second, Australians prefer to think of their political history in terms of heroes and villains (often embodied by the same individuals). Those binary roles require gregariousness, dynamism, some controversy, and the occasional serving of larrikinism. “Tall poppy syndrome” notwithstanding, partisan heroes like Menzies and Gough Whitlam, or infamous rats such as Billy Hughes, make for easy storytelling.

The forgettables are more often reserved, restrained or even polite characters. The Primitive Methodist Joseph Cook was “solemn and humourless”. The patrician Bruce was judged “too aloof and reserved to be an Australian”. And Frank Forde, in his old age, maintained that all of his colleagues and opponents had been “outstanding” and “capable men” for whom he had only “friendly feeling”. This is not exactly the stuff of masculine political legend.

Alfred Deakin has tended to absorb the historical limelight and cast long shadows over his contemporaries, not least because he furnished historians and biographers with rich personal papers. (Barton scrupulously destroyed most of his). But as Sean Scalmer has argued, we ought not to overlook the influence of Deakin’s contemporaries in the making of Australian politics as we know it.

Alfred Deakin (front row, second from right) has tended to cast a long shadow over his contemporaries. Australian Parliamentary Library

Third, prime ministers are rendered immemorable if they were judged to be temporary, or presiding over some kind of interregnum. Australians have valorised the longevity and stability of Menzies and Howard, or the sense of epochal change that accompanied Whitlam and Hawke. Men like Reid, Cook and Fadden seem transitory in comparison.

Fourth, public memory has often depended on the sponsorship of major parties and their affiliated scribes and institutes. The corollary is that those who preceded the two-party system are harder to commemorate. Labor has been excellent at proselytising its great leaders and their great reforms, and demonising the rats and renegades. The Liberal Party, on the other hand, has struggled to memorialise its antecedents and influences (Deakin perhaps excepted). Menzies and Howard predominate in the collective Liberal psyche, and Liberal forerunners from Barton to Bruce rarely get a look-in.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Joshua Black, PhD Candidate, School of History, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University

Last edited by a moderator: