Counting From Left To Right Feels ‘Natural’ – But New Research Shows Our Brains Count Faster From Bottom To Top

- Replies 20

When asked to write the numbers from one to ten in a sequence, how do you order them? Horizontally? Vertically? Left to right? Top to bottom? Would you place them randomly?

It has been often been assumed, and taught in schools in Western countries, that the “correct” ordering of numbers is from left to right (1, 2, 3, 4…) rather than right to left (10, 9, 8, 7…). The ordering of numbers along a horizontal dimension is known as a “mental number line” and describes an important way we represent number and quantity in space.

Studies show humans prefer to position larger numbers to the right and smaller numbers to the left. People are usually faster and more accurate at comparing numbers when larger ones are to the right and smaller ones are to the left, and people with brain damage that disrupts their spatial processing also show similar disruptions in number processing.

But so far, there has been little research testing whether the horizontal dimension is the most important one we associate with numbers. In new research published in PLOS ONE, we found that humans actually process numbers faster when they are displayed vertically – with smaller numbers at the bottom and larger numbers at the top.

Tests on three-day-old chicks show they seek smaller numberswith a leftwards bias and larger numbers with a rightwards one. Pigeons and blue jays seem to have a left-to-right or right-to-left mental number line, depending on the individual.

These findings suggest associations between space and numbers may be wired into the brains of humans and other animals.

However, while many studies have examined left-to-right and right-to-left horizontal mental number lines, few have explored whether our dominant mental number line is even horizontal at all.

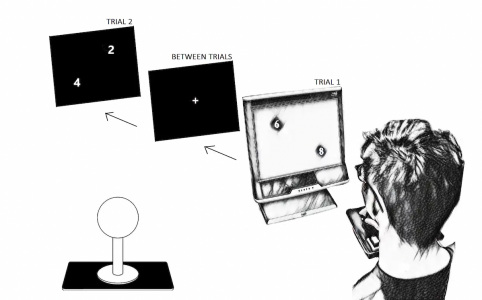

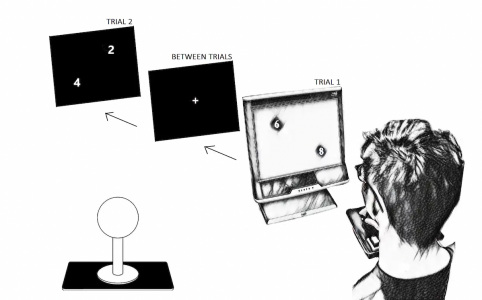

If the 6 and 8 were shown on the screen, for example, the correct answer would be 8. A participant would indicate this by moving the joystick towards the 8 as fast as possible.

To measure participant response times as accurately as possible, we used fast-refresh 120 Hertz monitors and high-performance zero-lag arcade joysticks.

Testing how participants show preferences for either horizontal or vertical mental number lines by indicating the larger number with a computer gaming joy stick.

When the larger number was above the smaller number, people responded much more quickly than in any other arrangement of numbers.

This suggests our mental number line actually goes from bottom (small numbers) to top (large numbers).

The way we learn to use numbers, and how designers choose to display numerical information to us, can have important implications for how we make fast and accurate decisions. In fact, in some time-critical decision-making environments, such as aeroplane cockpits and stock market floors, numbers are often displayed vertically.

Our findings, and another recent study, may have implications for designers seeking to help users quickly understand and use numerical information. Modern devices enable very innovative number display options, which could help people use technology more efficiently and safely.

There are also implications for education, suggesting we should teach children using vertical bottom-to-top mental number lines as well as the familiar left-to-right ones. Bottom-to-top appears to be how our brains are wired to be most efficient at using numbers – and that might help getting our heads around how numbers work a little easier.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Luke Greenacre Senior lecturer in marketing from Monash University, Adrian Dyer Associate Professor from Monash University, Jair Garcia Researcher and analyst from Monash University and Scarlett Howard Lecturer from Monash University

It has been often been assumed, and taught in schools in Western countries, that the “correct” ordering of numbers is from left to right (1, 2, 3, 4…) rather than right to left (10, 9, 8, 7…). The ordering of numbers along a horizontal dimension is known as a “mental number line” and describes an important way we represent number and quantity in space.

Studies show humans prefer to position larger numbers to the right and smaller numbers to the left. People are usually faster and more accurate at comparing numbers when larger ones are to the right and smaller ones are to the left, and people with brain damage that disrupts their spatial processing also show similar disruptions in number processing.

But so far, there has been little research testing whether the horizontal dimension is the most important one we associate with numbers. In new research published in PLOS ONE, we found that humans actually process numbers faster when they are displayed vertically – with smaller numbers at the bottom and larger numbers at the top.

Not just humans

Our associations between number and space are influenced by language and culture, but these links are not unique to humans.Tests on three-day-old chicks show they seek smaller numberswith a leftwards bias and larger numbers with a rightwards one. Pigeons and blue jays seem to have a left-to-right or right-to-left mental number line, depending on the individual.

These findings suggest associations between space and numbers may be wired into the brains of humans and other animals.

However, while many studies have examined left-to-right and right-to-left horizontal mental number lines, few have explored whether our dominant mental number line is even horizontal at all.

How we test for these spatial-numerical associations

To test how quickly people can process numbers in different arrangements, we set up an experiment where people were shown pairs of numbers from 1 to 9 on a monitor and used a joystick to indicate where the larger number was located.If the 6 and 8 were shown on the screen, for example, the correct answer would be 8. A participant would indicate this by moving the joystick towards the 8 as fast as possible.

To measure participant response times as accurately as possible, we used fast-refresh 120 Hertz monitors and high-performance zero-lag arcade joysticks.

Testing how participants show preferences for either horizontal or vertical mental number lines by indicating the larger number with a computer gaming joy stick.

What we found

When the numbers were separated both vertically and horizontally, we found only the vertical arrangement affected response time. This suggests that, given the opportunity to use either a horizontal or vertical mental representation of numbers in space, participants only used the vertical representation.When the larger number was above the smaller number, people responded much more quickly than in any other arrangement of numbers.

This suggests our mental number line actually goes from bottom (small numbers) to top (large numbers).

Why is this important?

Numbers affect almost every part of our lives (and our safety). Pharmacists need to correctly measure doses of medicine, engineers need to determine stresses on buildings and structures, pilots need to know their speed and altitude, and all of us need to know what button to press on an elevator.The way we learn to use numbers, and how designers choose to display numerical information to us, can have important implications for how we make fast and accurate decisions. In fact, in some time-critical decision-making environments, such as aeroplane cockpits and stock market floors, numbers are often displayed vertically.

Our findings, and another recent study, may have implications for designers seeking to help users quickly understand and use numerical information. Modern devices enable very innovative number display options, which could help people use technology more efficiently and safely.

There are also implications for education, suggesting we should teach children using vertical bottom-to-top mental number lines as well as the familiar left-to-right ones. Bottom-to-top appears to be how our brains are wired to be most efficient at using numbers – and that might help getting our heads around how numbers work a little easier.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Luke Greenacre Senior lecturer in marketing from Monash University, Adrian Dyer Associate Professor from Monash University, Jair Garcia Researcher and analyst from Monash University and Scarlett Howard Lecturer from Monash University