New diabetes breakthrough could mean the END of insulin injections

- Replies 7

Researchers studying diabetes claim to have made a discovery that may one day make it unnecessary to inject insulin daily.

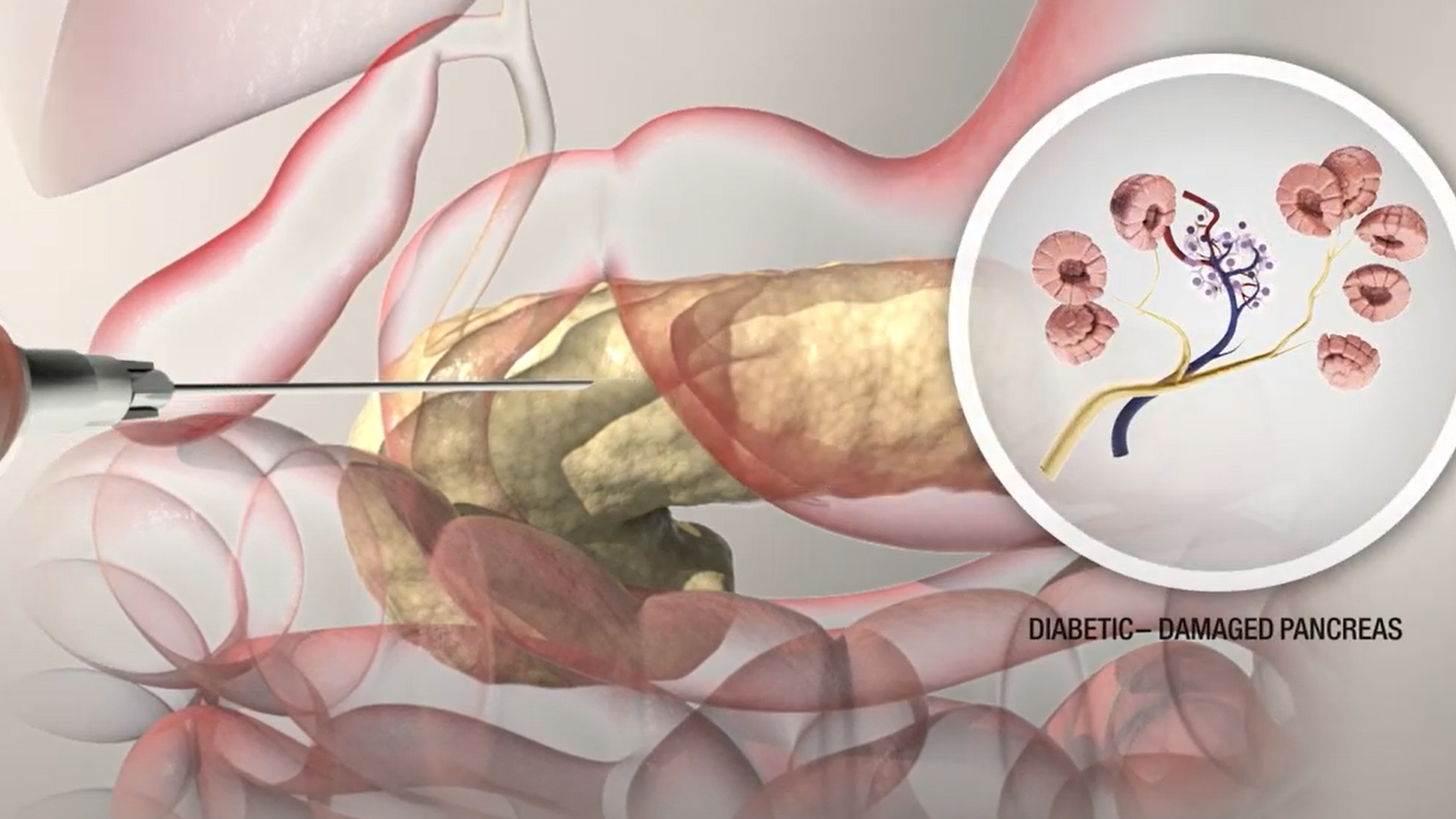

The findings of this study, which were recently published in the journal Nature's Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, have the potential to result in the regrowth of insulin-producing cells in pancreatic stem cells.

Insulin is a hormone that is produced by cells in the pancreas that are referred to as beta cells. Insulin is responsible for helping to control the amount of sugar in the blood.

Generally speaking, those who have diabetes do not produce enough insulin naturally, or their bodies do not use the hormone as they should. In many diabetic patients, the beta cells never produce any insulin.

Monash University scientists 'reprogrammed' type 1 diabetic pancreas cells to produce insulin. Credit: Monash University.

Dr Keith Al-Hasani, a researcher at Monash University and one of the study's authors, said, 'Diabetes comes in different forms, and it's a disease that needs constant attention.'

In most cases, patients are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when they are children. According to Dr Al-Hasani, this frequently results in the need for up to five injections of insulin each day as the young patient adjusts to living with the disease.

On the other hand, adult patients require up to a hundred shots per month just to keep their condition at bay.

Following the passing of a young boy, age 13, who had type 1 diabetes, the researchers investigated pancreatic cells that had been donated and used a compound to stimulate the production of insulin.

Dr Ishant Khurana, a fellow researcher and co-author of the study, explained that they are 'reprogramming' cells that don't typically produce insulin to do so now.

The compound they used is GSK126, which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for another condition. However, it has not been used to treat diabetes.

Dr Khurana referred to this discovery as a 'major breakthrough' in the field of diabetes.

Keith Al-Hasani and Ishanna Khurana, two researchers at Monash University, hope that their study will one day help treat diabetes. Credit: ABC/Rosanne Maloney.

Before the potential therapy can be applied to people, the authors acknowledged that there was still much work to be done.

In the following step, they plan to collect additional pancreatic cell samples from a wider variety of patients. After that, they will move on to trials on animals, and only then will they possibly begin clinical trials on humans.

The ultimate objective, according to Dr Khurana, was to do away with the need for pancreatic transplants and daily injections.

If successful, this new treatment would have an impact on the majority of Type 1 diabetics as well as the 30 per cent of Type 2 diabetics who also require insulin.

According to Diabetes Australia, approximately 1.8 million Aussies are living with diabetes, making it the illness with the highest rate of prevalence in the country. Globally, the number of people affected by the disease is approximately 500 million.

Simon McCrudden, now 46 years old, has been injecting his own insulin ever since he was seven years old. He believes that doing away with the need for daily injections would be a 'massive' relief.

'I've never known anything except diabetes and managing it,' he said. 'I inject four times a day. I have a long-lasting injection in the morning at 8 am, and then I have injections with each meal.'

'That's the holy grail, isn't it— If we can get to a point where diabetics don't have to inject, that would be amazing,' he said.

Here's to hoping that this research will lead to the end of the need for insulin injections in the future! What are your thoughts, members?

The findings of this study, which were recently published in the journal Nature's Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, have the potential to result in the regrowth of insulin-producing cells in pancreatic stem cells.

Insulin is a hormone that is produced by cells in the pancreas that are referred to as beta cells. Insulin is responsible for helping to control the amount of sugar in the blood.

Generally speaking, those who have diabetes do not produce enough insulin naturally, or their bodies do not use the hormone as they should. In many diabetic patients, the beta cells never produce any insulin.

Monash University scientists 'reprogrammed' type 1 diabetic pancreas cells to produce insulin. Credit: Monash University.

Dr Keith Al-Hasani, a researcher at Monash University and one of the study's authors, said, 'Diabetes comes in different forms, and it's a disease that needs constant attention.'

In most cases, patients are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when they are children. According to Dr Al-Hasani, this frequently results in the need for up to five injections of insulin each day as the young patient adjusts to living with the disease.

On the other hand, adult patients require up to a hundred shots per month just to keep their condition at bay.

Following the passing of a young boy, age 13, who had type 1 diabetes, the researchers investigated pancreatic cells that had been donated and used a compound to stimulate the production of insulin.

Dr Ishant Khurana, a fellow researcher and co-author of the study, explained that they are 'reprogramming' cells that don't typically produce insulin to do so now.

The compound they used is GSK126, which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for another condition. However, it has not been used to treat diabetes.

Dr Khurana referred to this discovery as a 'major breakthrough' in the field of diabetes.

Keith Al-Hasani and Ishanna Khurana, two researchers at Monash University, hope that their study will one day help treat diabetes. Credit: ABC/Rosanne Maloney.

Before the potential therapy can be applied to people, the authors acknowledged that there was still much work to be done.

In the following step, they plan to collect additional pancreatic cell samples from a wider variety of patients. After that, they will move on to trials on animals, and only then will they possibly begin clinical trials on humans.

The ultimate objective, according to Dr Khurana, was to do away with the need for pancreatic transplants and daily injections.

If successful, this new treatment would have an impact on the majority of Type 1 diabetics as well as the 30 per cent of Type 2 diabetics who also require insulin.

According to Diabetes Australia, approximately 1.8 million Aussies are living with diabetes, making it the illness with the highest rate of prevalence in the country. Globally, the number of people affected by the disease is approximately 500 million.

Simon McCrudden, now 46 years old, has been injecting his own insulin ever since he was seven years old. He believes that doing away with the need for daily injections would be a 'massive' relief.

'I've never known anything except diabetes and managing it,' he said. 'I inject four times a day. I have a long-lasting injection in the morning at 8 am, and then I have injections with each meal.'

'That's the holy grail, isn't it— If we can get to a point where diabetics don't have to inject, that would be amazing,' he said.

Here's to hoping that this research will lead to the end of the need for insulin injections in the future! What are your thoughts, members?