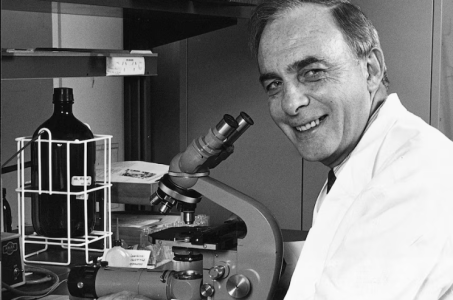

Creswell Eastman remembered for identifying health risks of iodine deficiency

By

ABC News

- Replies 19

He was dubbed "the man who saved a million brains" after discovering the critical link between iodine deficiency and cognitive function.

World-renowned endocrinologist, Creswell 'Cres' Eastman died peacefully at home last Saturday. He was 85.

Professor Eastman's life work was the prevention of iodine deficiency, especially in pregnant women, which leads to intellectual and physical disabilities in children.

It followed his discovery that the trace element in minuscule but daily doses was crucial to healthy brain function.

"You could put the whole amount of iodine you need for a lifetime into a teaspoon," Professor Eastman told Richard Fidler on Conversations in 2015, "so long as you don't take it all at once".

"It's absolutely essential for a normal life."

Friend and colleague Graeme Stuart said the significance of Professor Eastman's work improving the lives of millions of people could not be overstated.

"How many people in medicine and medical science could claim to have such an extraordinary impact? He would be there with a very small number, both in Australia and globally," Professor Stuart said.

"He was one of the most compassionate physicians that I've ever known, and an outstanding clinician in his ability to look after the whole patient."

Professor Stuart and other colleagues remembered the oft-quoted mantra he lived by: "The most basic human right you've got is the chance to fulfil your genetic potential".

Professor Eastman spent his career ensuring that potential was realised in people across Australia and Asia.

Ground-breaking work

During a visit to Sarawak in Malaysia in the early 1980s to study people with goitres, a swelling of the thyroid gland, Professor Eastman discovered a widespread deficiency of iodine in the diet.

While helping to fix the plumbing at one village, he facilitated the addition of iodine to the water supply. Twelve months later, goitres had all but disappeared in the village's young children.

This led the Malaysian government to legalise the importation of only iodised salt to Sarawak.

In China in the 1980s, Professor Eastman found one quarter of the population of more than a billion people had goitres, and of those, he estimated tens of millions had some form of brain damage.

"I went through some form of epiphany here, I thought, 'what's the point of just doing research here? We've got to translate that research into public health'," he said on Conversations.

"We've got to change the world.

"We've got to change what's happening in China. So I then started on a totally different mission."

Professor Eastman lobbied the Chinese government, resulting in a national law that salt for human consumption in China must be iodised.

The incidence of iodine deficiency dramatically reduced.

Getting salt iodised in Tibet proved a bigger challenge than in China; communities there traded crude salt, making it difficult to introduce an iodised product.

Instead, Professor Eastman worked on giving pregnant women an iodised oil capsule that reached 95 per cent of the population, resulting in no new cases of children with health defects.

This work in China and Tibet led him to be dubbed "the man who saved a million brains".

Iodine deficiency in Australia

The professor's research also benefited Australians.

Professor Eastman identified that dietary iodine in Australians was high in the 1950s and 60s through seafood and milk consumption.

He said milk was an unexpected source of iodine, "an accidental health triumph".

The dairy industry used iodine as a sanitiser to clean equipment, and people received trace elements of iodine in milk.

When the industry switched to chlorine in the 1990s, health experts noticed an increase in goitres.

"We were shocked to find the iodine levels in people we had been monitoring for 20 years had dropped dramatically," Professor Eastman said.

"The World Health Organization started painting Australia on the map with iodine deficiency as a Third World country."

The National Iodine Nutrition Survey, Professor Eastman helped conduct from 2003 to 2005, confirmed iodine deficiency had re-emerged in Australia.

This study led to the mandatory inclusion of iodised salt in most bread made from 2009.

However, with the rising popularity of gourmet salts, Professor Eastman remained concerned that pregnant women in Australia were not eating enough iodised salt.

His daughter Kate Eastman said her father was renowned for pulling the iodised salt to the front of supermarket shelves and hiding the non-iodised product.

"I was pregnant with my daughter, who is now 20. At that time, pink salt was very fashionable. I did not hear the end of it," Ms Eastman said.

"He accused me and my sister of our love of pink rock salt and fancy gourmet salts as being 'an aberration' … and his grandchildren were not suffering from any iodine deficiency.

"My father's message, if you had his words ringing in your ears, it's use iodised salt. So if you're in the supermarket … always get the iodised salt."

A fondness for Lismore

Creswell Eastman was born in Narrandera on March 30, 1940, to Albert and Margaret Eastman.

Just after World War II, the family moved to Evans Head, where they lived in a tent, before moving to Lismore.

Such was the housing shortage, the family lived in a fully furnished tent until a house became available.

Always a bright student, a young Creswell won two scholarships from the New South Wales government and the board of education to further his studies.

Legacy also helped pay for his education after his grandfather died when he was 11.

He married Annette Delaney, also from Lismore, and the couple had four children; Kate, Damien, Pip, and Nick.

Kate Eastman said her dad was dedicated to his wife and Lismore was close to their hearts.

"He spent his childhood in Lismore, going to school and to church in Lismore," Ms Eastman said.

After leaving the area, the family would regularly return to the region to holiday with Professor Eastman's sister, Margaret Rix and her husband Len, at their Ballina home.

Tributes

Professor Eastman worked at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, was a clinical professor of medicine at Sydney University Medical School, principal of the Sydney Thyroid Clinic, and consultant emeritus to the Westmead Hospital.

He received multiple awards, here and overseas and was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2018.

As family and friends farewell Professor Creswell Eastman, his daughter said the family was proud of their father's legacy, which he continued working on to the end.

"When he passed away, on his bedside table was an article on neo-natal health and iodine, and his little green marker was there — working till the end," she said.

"His life was devoted to the service of the health of others."

Written by Cathy Adams, ABC News.

World-renowned endocrinologist, Creswell 'Cres' Eastman died peacefully at home last Saturday. He was 85.

Professor Eastman's life work was the prevention of iodine deficiency, especially in pregnant women, which leads to intellectual and physical disabilities in children.

It followed his discovery that the trace element in minuscule but daily doses was crucial to healthy brain function.

"You could put the whole amount of iodine you need for a lifetime into a teaspoon," Professor Eastman told Richard Fidler on Conversations in 2015, "so long as you don't take it all at once".

"It's absolutely essential for a normal life."

Friend and colleague Graeme Stuart said the significance of Professor Eastman's work improving the lives of millions of people could not be overstated.

"How many people in medicine and medical science could claim to have such an extraordinary impact? He would be there with a very small number, both in Australia and globally," Professor Stuart said.

"He was one of the most compassionate physicians that I've ever known, and an outstanding clinician in his ability to look after the whole patient."

Professor Stuart and other colleagues remembered the oft-quoted mantra he lived by: "The most basic human right you've got is the chance to fulfil your genetic potential".

Professor Eastman spent his career ensuring that potential was realised in people across Australia and Asia.

Ground-breaking work

During a visit to Sarawak in Malaysia in the early 1980s to study people with goitres, a swelling of the thyroid gland, Professor Eastman discovered a widespread deficiency of iodine in the diet.

While helping to fix the plumbing at one village, he facilitated the addition of iodine to the water supply. Twelve months later, goitres had all but disappeared in the village's young children.

This led the Malaysian government to legalise the importation of only iodised salt to Sarawak.

In China in the 1980s, Professor Eastman found one quarter of the population of more than a billion people had goitres, and of those, he estimated tens of millions had some form of brain damage.

"I went through some form of epiphany here, I thought, 'what's the point of just doing research here? We've got to translate that research into public health'," he said on Conversations.

"We've got to change the world.

"We've got to change what's happening in China. So I then started on a totally different mission."

Professor Eastman lobbied the Chinese government, resulting in a national law that salt for human consumption in China must be iodised.

The incidence of iodine deficiency dramatically reduced.

Getting salt iodised in Tibet proved a bigger challenge than in China; communities there traded crude salt, making it difficult to introduce an iodised product.

Instead, Professor Eastman worked on giving pregnant women an iodised oil capsule that reached 95 per cent of the population, resulting in no new cases of children with health defects.

This work in China and Tibet led him to be dubbed "the man who saved a million brains".

Iodine deficiency in Australia

The professor's research also benefited Australians.

Professor Eastman identified that dietary iodine in Australians was high in the 1950s and 60s through seafood and milk consumption.

He said milk was an unexpected source of iodine, "an accidental health triumph".

The dairy industry used iodine as a sanitiser to clean equipment, and people received trace elements of iodine in milk.

When the industry switched to chlorine in the 1990s, health experts noticed an increase in goitres.

"We were shocked to find the iodine levels in people we had been monitoring for 20 years had dropped dramatically," Professor Eastman said.

"The World Health Organization started painting Australia on the map with iodine deficiency as a Third World country."

The National Iodine Nutrition Survey, Professor Eastman helped conduct from 2003 to 2005, confirmed iodine deficiency had re-emerged in Australia.

This study led to the mandatory inclusion of iodised salt in most bread made from 2009.

However, with the rising popularity of gourmet salts, Professor Eastman remained concerned that pregnant women in Australia were not eating enough iodised salt.

His daughter Kate Eastman said her father was renowned for pulling the iodised salt to the front of supermarket shelves and hiding the non-iodised product.

"I was pregnant with my daughter, who is now 20. At that time, pink salt was very fashionable. I did not hear the end of it," Ms Eastman said.

"He accused me and my sister of our love of pink rock salt and fancy gourmet salts as being 'an aberration' … and his grandchildren were not suffering from any iodine deficiency.

"My father's message, if you had his words ringing in your ears, it's use iodised salt. So if you're in the supermarket … always get the iodised salt."

Creswell Eastman was born in Narrandera on March 30, 1940, to Albert and Margaret Eastman.

Just after World War II, the family moved to Evans Head, where they lived in a tent, before moving to Lismore.

Such was the housing shortage, the family lived in a fully furnished tent until a house became available.

Always a bright student, a young Creswell won two scholarships from the New South Wales government and the board of education to further his studies.

Legacy also helped pay for his education after his grandfather died when he was 11.

He married Annette Delaney, also from Lismore, and the couple had four children; Kate, Damien, Pip, and Nick.

Kate Eastman said her dad was dedicated to his wife and Lismore was close to their hearts.

"He spent his childhood in Lismore, going to school and to church in Lismore," Ms Eastman said.

After leaving the area, the family would regularly return to the region to holiday with Professor Eastman's sister, Margaret Rix and her husband Len, at their Ballina home.

Tributes

Professor Eastman worked at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, was a clinical professor of medicine at Sydney University Medical School, principal of the Sydney Thyroid Clinic, and consultant emeritus to the Westmead Hospital.

He received multiple awards, here and overseas and was made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2018.

As family and friends farewell Professor Creswell Eastman, his daughter said the family was proud of their father's legacy, which he continued working on to the end.

"When he passed away, on his bedside table was an article on neo-natal health and iodine, and his little green marker was there — working till the end," she said.

"His life was devoted to the service of the health of others."

Written by Cathy Adams, ABC News.