Australia’s first ‘wellbeing budget’ revealed: We're living longer but…

- Replies 7

When the Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, delivers the country's federal budget each year, the focus of the address is almost always on key economic indicators like GDP, wage growth, and prices of exports.But recently, economists and social policymakers have begun to suggest that governments should look beyond the 'traditional' measures of economic performance and take into account the natural environment, poverty, and quality of life as well.

At last, the Australian government has embraced this idea, with Friday seeing the first-ever release of a 'wellbeing budget' in Australia.

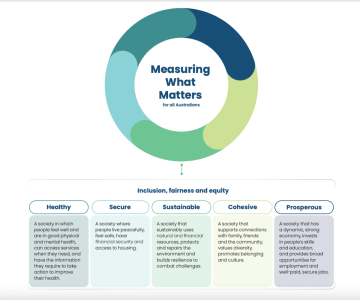

‘Measuring What Matters’ is Australia’s first-ever national wellbeing framework, built from over 280 submissions from people and organisations and more than 65 meetings.

This report, modelled after similar initiatives seen in the likes of Canada, New Zealand, and Germany, looks beyond the number of dollars in our bank accounts and into 50 different indicators that measure the various aspects of our lives; from life expectancy and leisure time to trust in institutions, the number of people sleeping rough, and even the amount of time we spend listening to podcasts.

We're sure you're particularly curious about one of the report's central aspects of wellbeing: life expectancy. A woman born today can expect to live up to 85.4 years, and a man up to 81.3 years.

But it's not just about quantity, but quality. This also means that Australians will be dealing with chronic illnesses for a much longer period of time due to the improvement of healthcare management in the country.

Speaking of quality of life, recent years have seen a decline in people feeling lonely, with leisure time remaining steady (around 3.5 hours a day spent in front of the TV and over two hours tuning into radio or podcasts). Interestingly, older audiences (those aged 55+) are the most likely to attend cultural and art events (78%).

Volunteer work, however, is on the decline, with only a quarter of Australians dedicating their time to helping out their community.

Economically, the level of debt held by governments has gone down compared to figures from 2008, while national income per person has increased for the past two decades.

Despite Australia proudly standing as the world's 12th largest economy, the report sadly points out our narrow foundation. Surprisingly, we only rank 91st out of 133 when it comes to economic complexity, which tracks how a nation channels knowledge into complex industries. We sit just behind Kenya and Laos and only slightly ahead of Bangladesh and Tajikistan.

However, by no means is this a complete success story. Flora and fauna are under threat, with a 55% drop in the number of 278 monitored species of animals, birds, reptiles, and fish. And more people than ever face the risk of homelessness.

Australians aged 70 years and over were found to be more likely to trust others compared to those aged 15–24. Even with increasing trust in our neighbours, faith in the federal government has seen a significant dip.

The wellbeing program director for the Centre for Policy Development think tank, Warwick Smith, noted that the wellbeing report is a crucial component to understanding the challenges faced by Australians daily.

‘The traditional measures are important, but they don’t give the full picture. Think of this as an upgrade from street directory to GPS,’ he said.

Chalmers, though mocked by then-treasurer Josh Frydenberg for the idea of a wellbeing budget, sees it as an essential measure for understanding both the country’s economic challenges and broader concerns that affect a person's wellbeing.

'While Australia performs relatively well compared to similar countries on international indicators, we know there is more we can do to improve the wellbeing of our people and communities,' he said.

Current indicators are available on an online dashboard which will be updated annually.

You can view the online dashboard here.

The good

- Life expectancy at birth (women 85.4 years/men 81.3 years)

- Trust in other people (was 54.1% in 2006, 61.4% in 2020)

- National income per capita (was $48,538 in 2002-03, now $68,092)

- Waste generated per person (was 3.05 tonnes in 2006-07, now 2.95 tonnes)

- Biological diversity (55% drop in the abundance of 278 species since 1985)

- Productivity (Australia's productivity growth level has slowed to 1.2%)

- Homelessness (was 45 per 10,000 people in 2006, now at 48 per 10,000)

- Trust in national government (53.2% of people win 2006, now at 49.9%)

- The proportion of people experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress (steady at 13%)

- Income and wealth inequality (steady since 2007-08)

- Life satisfaction (steady between 2014 and 2019)

Outdated data raises concerns

The major criticism over Mr Chalmers' first attempt at a wellbeing budget revolves around the dated data used to back the findings. For instance, the claim that homeowners are finding it easier to repay mortgages comes from information predating the rapid tightening of interest rates on homeowners.

The cherry on this controversial cake is a claim about mental health. According to the wellbeing report, Aussies' mental health is 'stable'. Yet the report uses surveys from way back in 2005 and 2018, a time before COVID-19 turned our lives upside down and caused a surge in psychological distress.

Opposition home affairs spokesman James Paterson has jumped in, criticising the data as being so outdated it 'might as well been from the last century'.

Treasurer Chalmers defended his budget, stating, 'We haven't had a national wellbeing framework before, this is the first attempt of it. And one of the things that it makes clear is that we need to do collectively a better job of measuring our progress over time.'

‘We know where the gaps in the data are, we know where we need it to be more regular, we know where we need to fill those gaps.’

So what did Chalmers have to say about the financial pressure in Australia?

‘That is our focus, on rolling out billions of dollars of cost of living help. We are doing that at the same time as we bring the budget back to surplus. At the same time, there is half a million jobs that are being created, a record for a new government.’

‘Our focus is firmly on pressures that people are under, on rolling out our economic plan including cost of living help but that should not come at the expense of leading a national conversation about how we better align our social and economic objectives.’

Key Takeaways

- The wellbeing report, Australia’s first, tracks 50 indicators covering health, security, the environment, the economy and society, demonstrating that while in some areas the country has improved, in others it has deteriorated.

- Treasurer Jim Chalmers has defended his wellbeing budget amid criticisms for using outdated data.

- The report, titled 'Measuring What Matters', used old data which was perceived to be misleading on issues like homeowners' mortgage repayment and Australians' mental health status.

- Despite the backlash, Chalmers stressed the need for ongoing improvements to the data collection process for a more accurate reflection of Australians' wellbeing in future reports.

- The report identified both improvements and challenges in Australians' life over the past two decades, such as increased life expectancy and job satisfaction, but also a rise in Australians living with chronic conditions.

Australia may be the world's twelfth-largest economy, but as the wellbeing report shows us, we must consider more than dollars and cents when approaching and understanding the wellbeing of our society.

The framework will be refined in future statements, and indicators will be tracked on an online dashboard which will be updated annually. As always, we’ll keep you in the loop when relevant updates arise.

In the meantime, what are your thoughts on Australia’s first wellbeing framework?