What voluntary assisted dying options are available for those with dementia?

By

ABC News

- Replies 0

Disclaimer: This article talks about distressing topics related to dementia and death. Reader discretion is advised.

John Griffiths suspects his mind is starting to fail.

It is a horrifying prospect for the father-of-three, former Monash University engineering lecturer and CSIRO research scientist.

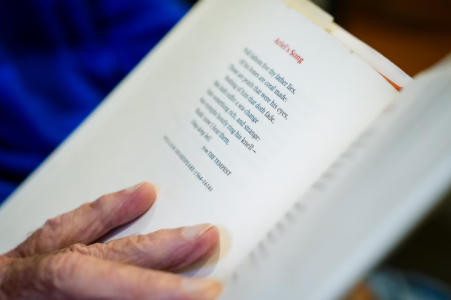

The Melbourne man spends much of his time with his wife Rachel, who lives in residential aged care, reading her poems and short stories.

"I've got nothing but praise for [her] carers. I think they're fantastic, professional and excellent," he said.

"But, nevertheless, there's this total loss of autonomy."

While doctors say he is all clear at the moment, he will be assessed for dementia in the next year. If he does develop the condition, he would rather die than let it take hold.

But his options are limited.

Although voluntary assisted dying (VAD) will be legal in every Australian jurisdiction except the Northern Territory by the end of this year, it remains entirely off-limits for people with dementia.

Instead, Mr Griffiths is considering a one-way ticket to Switzerland.

The clock, however, is ticking.

While the European nation is famous for the broad access it permits to end-of-life services, a person must still have "mental capacity".

Mr Griffiths worries if he goes too early, he will needlessly shave years off his life, but if he leaves it too late, he may become ineligible.

"This is now a terribly difficult thing I have to do, if I want to access (VAD)," he said.

"I have to do it while I'm cognitively aware."

"I don't want to leave it too late. But I don't want to make it too early either."

He suspects other Australians will soon find themselves at a similar crossroads.

The right to die abroad

Unlike most countries, Switzerland allows people to voluntarily end their lives, even if they are not sick nor a citizen.

A report published by Australian charity Go Gentle this year cited data from one right-to-die association, claiming 38 Australians travelled to Switzerland to die between 1998 and 2021.

Switzerland's right-to-die organisations charge a fee of between $20,000 and $30,000, excluding travel and accommodation, to procure the medication and handle the aftermath of the death, including cremation or transport of the body.

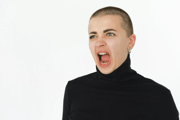

Neuropsychologist Kylie Ladd, who has worked with dementia patients for 30 years and authored the Go Gentle report, said a person had to pass a series of interviews and be deemed to "have capacity" before they could proceed.

"It is theoretically possible that people in Australia with early dementia who still retain capacity could go to Switzerland to end their lives," Dr Ladd said.

Now that VAD is legal across much of the country, statistics on how many Australians are still going to Switzerland are hard to come by.

Philip Nitschke, who has been the subject of long-running controversy, founded Exit International to advocate for end-of-life services around the world.

He estimated about one to two Australians are continuing to travel abroad to end their lives each month.

But even he, a vocal supporter of VAD, said dementia posed a particularly difficult problem.

An advance request

Dementia now ranks among the leading causes of death across many developed nations.

With rates only set to increase, health departments all over the world are grappling with the question of VAD for those with the disorder.

But relevant Australian peak bodies, including Dementia Australia, Council on the Ageing and Palliative Care Australia, said they were neutral on the subject.

The Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium allow VAD for dementia patients through an Advance Care Directive, a legal document setting out a person's healthcare wishes for when they can no longer make them.

But uptake has been low.

Dementia patients constituted only 3.7 per cent of all VAD deaths in the Netherlands in 2023.

In Belgium only 0.95 per cent of VAD deaths were people with cognitive disorders, including many forms of dementia, between 2018 and 2021.

In both cases, most patients had only early-stage dementia.

Loved ones back out

Dr Ladd said many doctors and loved ones baulked at the idea of ending the life of a person "who doesn't know what's going on".

She cited a Dutch study that found three in four relatives of nursing home residents with advanced dementia asked physicians not to act on their loved ones' request for VAD through Advance Care Directives.

Another study found support for the idea dropped dramatically once survey participants were given specific scenarios and asked whether VAD should be administered.

"Public acceptance … has been shown to decrease significantly when the situation moves from being a theoretical question to a lived reality," she wrote.

There are also legal issues.

In the Netherlands in 2016, a criminal investigation was launched into a physician who complied with an elderly dementia patient's Advance Care Directive, after it emerged the patient pulled away when given the fatal dose.

Philosophical questions

Along with practical hurdles, Dr Ladd said Dutch ethicists were grappling with philosophical questions.

They ask whether a person who draws up an Advance Care Directive is still the same person once dementia takes hold, and whether it is possible for a competent person to foresee what life with dementia would be like.

If the answer to either question is "no", it may invalidate the document.

"They're not just medical issues. They're not just legal issues," Dr Ladd said.

"They're really knotty ethical issues as well."

A technical solution

Dr Nitschke believed while the Dutch should be commended for grappling with VAD for dementia patients, problems would always arise in "outsourcing death".

He believed technology would provide a better option.

"Instead of outsourcing your death to someone else, like the medical profession, you're taking responsibility for your own death," Dr Nitschke said.

His approach has been disputed in the past.

Last year, his organisation opened The Last Resort, designed to let people die for free using specially designed pods.

But after one was used successfully, several staff were detained on suspicion of aiding and abetting suicide. They were eventually released.

Dr Nitschke argued it was important to give people options, and noted a key benefit of the Dutch system was the peace of mind it offered, particularly after a dementia diagnosis.

"That's by far the biggest benefit we're seeing in the Netherlands," he said.

"It does give people comfort to know that they've signed a piece of paper, even though there might be a thin chance that anyone will act on it."

'A great comfort'

It would certainly be a comfort to Mr Griffiths.

The Melbourne man said he did not know how Australian VAD laws should be written, or what he would do when "push comes to shove".

But he said he would not make any decision about his own death until his wife had passed away.

"I think it'd be a bit selfish to go before she does," he said.

When the end is approaching, he said it would be a relief to know he could die on his own terms with dementia in Australia.

"Very much so," he said.

"Everyone says once you get the OK it gives you a lot of peace.

"Whether or not you access it or not is not such a big drama.

"I think it would be a great comfort."

Written by Emily JB Smith, ABC News.

Learn more about Australia's voluntary assisted death laws in this article by retired psychologist and SDC member @Joy Straw.

John Griffiths suspects his mind is starting to fail.

It is a horrifying prospect for the father-of-three, former Monash University engineering lecturer and CSIRO research scientist.

The Melbourne man spends much of his time with his wife Rachel, who lives in residential aged care, reading her poems and short stories.

"I've got nothing but praise for [her] carers. I think they're fantastic, professional and excellent," he said.

"But, nevertheless, there's this total loss of autonomy."

While doctors say he is all clear at the moment, he will be assessed for dementia in the next year. If he does develop the condition, he would rather die than let it take hold.

But his options are limited.

Although voluntary assisted dying (VAD) will be legal in every Australian jurisdiction except the Northern Territory by the end of this year, it remains entirely off-limits for people with dementia.

Instead, Mr Griffiths is considering a one-way ticket to Switzerland.

The clock, however, is ticking.

While the European nation is famous for the broad access it permits to end-of-life services, a person must still have "mental capacity".

Mr Griffiths worries if he goes too early, he will needlessly shave years off his life, but if he leaves it too late, he may become ineligible.

"This is now a terribly difficult thing I have to do, if I want to access (VAD)," he said.

"I have to do it while I'm cognitively aware."

"I don't want to leave it too late. But I don't want to make it too early either."

He suspects other Australians will soon find themselves at a similar crossroads.

The right to die abroad

Unlike most countries, Switzerland allows people to voluntarily end their lives, even if they are not sick nor a citizen.

A report published by Australian charity Go Gentle this year cited data from one right-to-die association, claiming 38 Australians travelled to Switzerland to die between 1998 and 2021.

Switzerland's right-to-die organisations charge a fee of between $20,000 and $30,000, excluding travel and accommodation, to procure the medication and handle the aftermath of the death, including cremation or transport of the body.

Neuropsychologist Kylie Ladd, who has worked with dementia patients for 30 years and authored the Go Gentle report, said a person had to pass a series of interviews and be deemed to "have capacity" before they could proceed.

"It is theoretically possible that people in Australia with early dementia who still retain capacity could go to Switzerland to end their lives," Dr Ladd said.

Now that VAD is legal across much of the country, statistics on how many Australians are still going to Switzerland are hard to come by.

Philip Nitschke, who has been the subject of long-running controversy, founded Exit International to advocate for end-of-life services around the world.

He estimated about one to two Australians are continuing to travel abroad to end their lives each month.

But even he, a vocal supporter of VAD, said dementia posed a particularly difficult problem.

An advance request

Dementia now ranks among the leading causes of death across many developed nations.

With rates only set to increase, health departments all over the world are grappling with the question of VAD for those with the disorder.

But relevant Australian peak bodies, including Dementia Australia, Council on the Ageing and Palliative Care Australia, said they were neutral on the subject.

The Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium allow VAD for dementia patients through an Advance Care Directive, a legal document setting out a person's healthcare wishes for when they can no longer make them.

But uptake has been low.

Dementia patients constituted only 3.7 per cent of all VAD deaths in the Netherlands in 2023.

In Belgium only 0.95 per cent of VAD deaths were people with cognitive disorders, including many forms of dementia, between 2018 and 2021.

In both cases, most patients had only early-stage dementia.

Loved ones back out

Dr Ladd said many doctors and loved ones baulked at the idea of ending the life of a person "who doesn't know what's going on".

She cited a Dutch study that found three in four relatives of nursing home residents with advanced dementia asked physicians not to act on their loved ones' request for VAD through Advance Care Directives.

Another study found support for the idea dropped dramatically once survey participants were given specific scenarios and asked whether VAD should be administered.

"Public acceptance … has been shown to decrease significantly when the situation moves from being a theoretical question to a lived reality," she wrote.

There are also legal issues.

In the Netherlands in 2016, a criminal investigation was launched into a physician who complied with an elderly dementia patient's Advance Care Directive, after it emerged the patient pulled away when given the fatal dose.

Along with practical hurdles, Dr Ladd said Dutch ethicists were grappling with philosophical questions.

They ask whether a person who draws up an Advance Care Directive is still the same person once dementia takes hold, and whether it is possible for a competent person to foresee what life with dementia would be like.

If the answer to either question is "no", it may invalidate the document.

"They're not just medical issues. They're not just legal issues," Dr Ladd said.

"They're really knotty ethical issues as well."

A technical solution

Dr Nitschke believed while the Dutch should be commended for grappling with VAD for dementia patients, problems would always arise in "outsourcing death".

He believed technology would provide a better option.

"Instead of outsourcing your death to someone else, like the medical profession, you're taking responsibility for your own death," Dr Nitschke said.

His approach has been disputed in the past.

Last year, his organisation opened The Last Resort, designed to let people die for free using specially designed pods.

But after one was used successfully, several staff were detained on suspicion of aiding and abetting suicide. They were eventually released.

Dr Nitschke argued it was important to give people options, and noted a key benefit of the Dutch system was the peace of mind it offered, particularly after a dementia diagnosis.

"That's by far the biggest benefit we're seeing in the Netherlands," he said.

"It does give people comfort to know that they've signed a piece of paper, even though there might be a thin chance that anyone will act on it."

It would certainly be a comfort to Mr Griffiths.

The Melbourne man said he did not know how Australian VAD laws should be written, or what he would do when "push comes to shove".

But he said he would not make any decision about his own death until his wife had passed away.

"I think it'd be a bit selfish to go before she does," he said.

When the end is approaching, he said it would be a relief to know he could die on his own terms with dementia in Australia.

"Very much so," he said.

"Everyone says once you get the OK it gives you a lot of peace.

"Whether or not you access it or not is not such a big drama.

"I think it would be a great comfort."

Written by Emily JB Smith, ABC News.

Learn more about Australia's voluntary assisted death laws in this article by retired psychologist and SDC member @Joy Straw.