We All Lose When Charities Compete With Each Other. They Should Join Forces

- Replies 13

You want to help Ukrainians in need. Should you donate to UNICEF, UNHCR, Red Cross, World Vision, Caritas, Save the Children or some other charitable organisation?

There are so many charities, and charitable causes, to choose from.

Australia, for example, has more than 57,500 registered charities (for a population of 25 million). The UK (population 67 million) has more more than 200,000. The US (population 350 million) has close to 1.5 million.

They’re vying against direct competitors as well as every other charity and cause. Suicide prevention is up against wilderness conservation. Cancer research against climate change activism. Refugee aid against the arts.

Not all actively fundraise – in Australia only about 40% do – but that still leaves thousands competing for your money.

And that competition is hurting them.

There are concerns aggressive marketing, from phone calls to junk mail to “edgy” advertising, is turning people off donating to any charity.

A classic example is the UK Pancreatic Cancer Action’s “I wish I had” campaign. It compared the 3% survival rate for pancreatic cancer to 97% for testicular cancer and 85% for breast cancer. The campaign attracted attention, but not in the way the organisation hoped.

The UK Pancreatic Cancer Action’s ‘I wish I had breast cancer’ campaign proved controversial. UK Pancreatic Cancer Action, CC BY

Though there’s no hard data proving competition is contributing to donor fatigue, there is strong anecdotal evidence.

The UK’s Fundraising Regulator has been cracking down on aggressive fundraising since a 2015 case in which a 92-year-old woman committed suicide after receiving 466 mailings from 99 charities in a year. Last month it updated its service to stop direct marketing communications from charities, allowing people to block ten charities at a time.

In the US, the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy has found that even though total donations have been increasing, the share of Americans donating has declined – from two-thirds in 2000 to half in 2018.

The report doesn’t speculate on the causes, but given the well-established phenomenon of choice overload, it’s reasonable to assume too much competition plays a part.

This was highlighted in a 2020 report by Britain’s National Council for Voluntary Organisations, warning of competitive behaviour’s “negative impact on the sector, people and places”.

The report’s focus was mostly on competition in bidding for government service contract. but its conclusions also apply to competition for public donations

The “uncool” causes also lose out. This is well-known in conservation fundraising, where large and cute animals outdo ugly ones.

It also occurs with diseases. The breast cancer lobby in Australia, for example, has been likened to a “pink steamroller”, diverting funding and public awareness away from other forms of cancer.

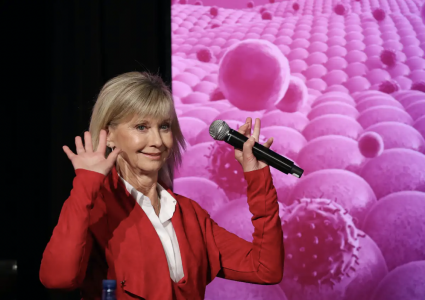

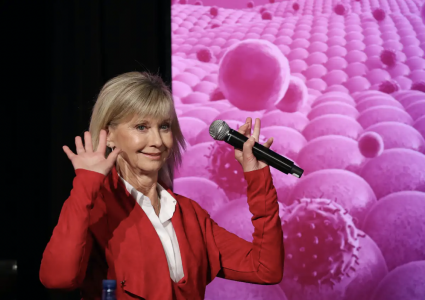

Celebrity power has contributed to this. Breast cancer survivor Olivia Newton-John, for example, has been a passionate fundraiser for research, establishing the Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness & Research Centre.

Olivia Newton-John addresses the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Research Conference in Melbourne in September 2019. David Crosling/AAP, CC BY

So too has champion cricketer Glenn McGrath, who established the McGrath Foundation after his wife Jane died of breast cancer. The foundation has a high-profile association with Cricket Australia, which hosts the annual Sydney Pink Test to raise money for breast cancer services.

Spectators dress in pink for ‘Jane McGrath Day’ during the fourth Ashes Test between Australia and England at the Sydney Cricket Ground in January 2022. Dan Himbrechts/AAP

Co-operative marketing structures are common in sectors such as agriculture. They are also used in retailing, where small independent stores, travel agents and newsagencies have pooled their marketing resources to compete with large corporate rivals.

Applying this approach would mean, for example, that cancer charities – breast, bowel, leukaemia, lung, myeloma, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate – would fund campaigns coordinated by an umbrella organisation. Proceeds could then be split more equitably, based on expert input about research and support needs.

The benefits of greater co-operation have been talked about for years with no much progress made.

But there’s nothing like an idea whose time has come, and with every passing year the case for charitable co-operation grows.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by David Waller Associate Professor from University of Technology Sydney, Phillip Morgan Associate lecturer, University of Newcastle

There are so many charities, and charitable causes, to choose from.

Australia, for example, has more than 57,500 registered charities (for a population of 25 million). The UK (population 67 million) has more more than 200,000. The US (population 350 million) has close to 1.5 million.

They’re vying against direct competitors as well as every other charity and cause. Suicide prevention is up against wilderness conservation. Cancer research against climate change activism. Refugee aid against the arts.

Not all actively fundraise – in Australia only about 40% do – but that still leaves thousands competing for your money.

And that competition is hurting them.

The downsides of competition

Research by University of Washington economist Bijetri Bose suggests greater competition among non-profits marginally increases aggregate donations but reduces average donations per organisation. Fundraising costs also escalate with greater competition.There are concerns aggressive marketing, from phone calls to junk mail to “edgy” advertising, is turning people off donating to any charity.

A classic example is the UK Pancreatic Cancer Action’s “I wish I had” campaign. It compared the 3% survival rate for pancreatic cancer to 97% for testicular cancer and 85% for breast cancer. The campaign attracted attention, but not in the way the organisation hoped.

The UK Pancreatic Cancer Action’s ‘I wish I had breast cancer’ campaign proved controversial. UK Pancreatic Cancer Action, CC BY

Though there’s no hard data proving competition is contributing to donor fatigue, there is strong anecdotal evidence.

The UK’s Fundraising Regulator has been cracking down on aggressive fundraising since a 2015 case in which a 92-year-old woman committed suicide after receiving 466 mailings from 99 charities in a year. Last month it updated its service to stop direct marketing communications from charities, allowing people to block ten charities at a time.

In the US, the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy has found that even though total donations have been increasing, the share of Americans donating has declined – from two-thirds in 2000 to half in 2018.

The report doesn’t speculate on the causes, but given the well-established phenomenon of choice overload, it’s reasonable to assume too much competition plays a part.

Unfair competition

As well as the issues already mentioned, competition generally disadvantages smaller charities.This was highlighted in a 2020 report by Britain’s National Council for Voluntary Organisations, warning of competitive behaviour’s “negative impact on the sector, people and places”.

The report’s focus was mostly on competition in bidding for government service contract. but its conclusions also apply to competition for public donations

The “uncool” causes also lose out. This is well-known in conservation fundraising, where large and cute animals outdo ugly ones.

It also occurs with diseases. The breast cancer lobby in Australia, for example, has been likened to a “pink steamroller”, diverting funding and public awareness away from other forms of cancer.

Celebrity power has contributed to this. Breast cancer survivor Olivia Newton-John, for example, has been a passionate fundraiser for research, establishing the Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness & Research Centre.

Olivia Newton-John addresses the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Research Conference in Melbourne in September 2019. David Crosling/AAP, CC BY

So too has champion cricketer Glenn McGrath, who established the McGrath Foundation after his wife Jane died of breast cancer. The foundation has a high-profile association with Cricket Australia, which hosts the annual Sydney Pink Test to raise money for breast cancer services.

Spectators dress in pink for ‘Jane McGrath Day’ during the fourth Ashes Test between Australia and England at the Sydney Cricket Ground in January 2022. Dan Himbrechts/AAP

Is more co-operation possible?

Could charities compete less and co-operate more?Co-operative marketing structures are common in sectors such as agriculture. They are also used in retailing, where small independent stores, travel agents and newsagencies have pooled their marketing resources to compete with large corporate rivals.

Applying this approach would mean, for example, that cancer charities – breast, bowel, leukaemia, lung, myeloma, ovarian, pancreatic and prostate – would fund campaigns coordinated by an umbrella organisation. Proceeds could then be split more equitably, based on expert input about research and support needs.

The benefits of greater co-operation have been talked about for years with no much progress made.

But there’s nothing like an idea whose time has come, and with every passing year the case for charitable co-operation grows.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by David Waller Associate Professor from University of Technology Sydney, Phillip Morgan Associate lecturer, University of Newcastle