'Scambling' is an online gambling scam targeting First Nations communities

By

ABC News

- Replies 0

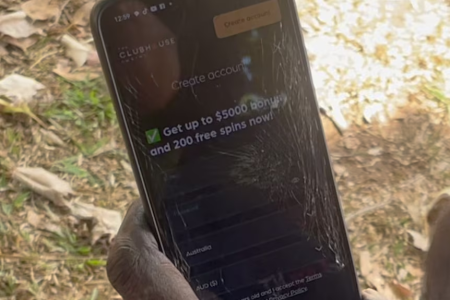

In a remote Northern Territory community, grandmother Gloria signed up to a brightly coloured pokie-style website, lured by the offer of thousands of dollars in free spins and bonuses, but the game never paid.

Gloria, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, first heard of the "ding ding" game from her daughter about a year ago.

To play, she would transfer $50 to $150 to different PayID accounts, and while she thought she was winning big, it was just a ruse.

"I was playing a three-game bonus … I won $9,200 and withdrew and submitted and [the website] just took all that money and just gave me to play my own money, $20."

Gloria never saw any cash land in her bank account and she lost access to the site.

"It's a shame job," the 60-year-old said.

Gambling scams, known as "scambling" or "ding ding", are having a "catastrophic" impact on First Nations communities, financial counsellors told the ABC.

They said people signing up to illegal pokies and casino sites in the hope of banking big wins are unknowingly being scammed and embroiled in "micro money laundering".

Players are enticed by free credits and then asked to make regular transfers of cash to a PayID via phone numbers or emails, despite there being little chance of winning.

Casino and blackjack sites are illegal under Australian law so there are no protections for players, and financial intelligence agency AUSTRAC warned if players pay via PayID, the website is "almost certainly a scam".

AUSTRAC acting CEO John Moss said scambling had rapidly evolved into a "sophisticated and pervasive financial crime threat".

Counsellors told the ABC these sites were "highly addictive" and sent spam messages to keep the player engaged.

CatholicCare NT's Kelly Gulliver said she had never seen such devastation from one type of scam in her 25 years working in the sector.

"At first, there is a little bit of incentive [for the player where] they might get some small wins and there are some incentives like free spins if they refer friends and family," she said.

"They are impacted by the false pretence that there is an opportunity for them to win, and they don't really know that it is illegal."

Financial counsellors said the sites were being shared via WhatsApp groups, ads on social media and occasionally through apps on legitimate websites like the Google Play Store and Apple App Store.

Ms Gulliver first noticed the trend among clients who needed help applying for no-interest loans or emergency relief for food.

When she assessed their bank statements, she saw regular PayID payments of small amounts of money.

"A year ago we saw the odd bank account with these patterns of transactions, [but] now in some communities it's almost maybe 80–90 per cent of people that we support," she said.

"It is absolutely scary … the impacts of it are catastrophic."

While her analysis is ongoing, she has calculated more than 80 areas in the NT that are impacted.

"They're geo-targeting First Nations communities," she said.

"It's definitely predatory and unethical, so they're coming up on their social media feeds, they're getting messages through WhatsApp, and really we're not seeing any other communities or groups impacted by this yet."

Queensland-based Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network's financial counsellor Alex Price-Busch said he noticed the uptick in users after COVID-19.

"One of the worst examples was a client who received a redress payment and in a mixture of them depositing money onto the site, as well as the access that the site had to their bank, essentially their entire redress payment was siphoned out," the First Nations man said.

"You have people putting in significant amounts of money to chase a win and even if they get that, they might not be able to withdraw it, which doubles the pain and frustration they are already experiencing."

Financial Counselling Australia (FCA) said the scam was "spreading like wildfire" among mob in the NT, WA, NSW and QLD.

Its director of First Nations policy, Lynda Edwards, said the small amounts spent on these sites added up, leaving people without money for essential items.

"It's definitely one of the worst scams I've ever seen … people are losing hundreds of dollars every day," she said.

"We know that they're not only just losing money, but there's the challenges and the problems in the community around family and domestic violence when there's not enough money to pay bills."

That included almost $373,000 lost to betting and sports investment scams, which represented a 797 per cent increase.

Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC) deputy chair Catriona Lowe told the ABC they were in the process of finding out more about the "emerging scam type".

"It presents as online betting, but there is 'micro laundering' element to it, so it can actually be in addition to people losing money to the scam," she said.

Financial crime authority AUSTRAC said criminal syndicates or organised crime groups were suspected of being behind illegal online gaming sites.

It warns that it is highly unlikely that authorities in Australia will be able to recover lost funds through these sites.

AUSTRAC's Dr Moss said the authority's Fintel Alliance had identified multiple cases where players in remote and Indigenous communities inadvertently became "money mules" for organised crime groups.

Banks often responded by freezing the person's bank accounts, CatholicCare NT's Kelly Gulliver said, leaving them without money for food and essentials.

Lynda Edwards, a descendant of the Wangkumara people of far west NSW, said they have heard people were handing over banking details for money.

"They are saying to people who are living on the edge and that are really, really poor, we'll give you $1,500 if you let us have your bank account … just for a short amount of time."

Gloria's bank account was suspended and now she is warning her family not to play or risk losing access to their money.

"I saw different people named on my internet banking," the retiree said.

"Tell them to stop playing ding ding, they just waste a lot of money."

"It is millions of dollars that people are potentially losing and there is not enough protection in place to ensure that they are not at risk," ICAN's Alex Price-Busch said.

ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe said the National Anti-Scam Centre was prioritising the identification of scam gambling websites to refer them for take-down.

"Through close collaboration with banks and digital platforms, we focus on preventing scam contact, stopping interactions that are already underway, and blocking payments before funds are lost."

Mr Price-Busch described the online gaming sites as like "whack-a-mole", where one unregulated gambling domain pops up, another one with a similar name takes its place.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) publishes legitimate gambling operators, as well as those that have been banned.

Since 2017, more than 1,290 websites have been blocked, including 270 websites in the past year.

ACMA said if people accessed those blocked sites, they would receive a warning message.

The Australian Banking Association told the Indigenous Affairs Team that "some banks are already undertaking consumer awareness initiatives to help people identify the risks".

"Banks will pursue further discussions with consumer representatives, including whether new provisions to require the taking down of fraudulent apps are required."

The ACCC urges victims to stop, check and protect, and if people are victims, to report to Scamwatch and seek assistance from the cyber support service IDCARE.

Scambling is not the only scam targeting Indigenous communities.

In the first six months of 2025, nearly a million dollars was lost by First Nations people through investment scams such as fake term deposits.

Shopping scams accounted for 162 Indigenous people's losses — a nearly 60 per cent increase on last year, while there was a 116 per cent increase to jobs scams.

"Scamming is at its heart a numbers game, so scammers will typically cast their net wide and see if they can get a bite," Ms Lowe said.

"Where there are language barriers, or indeed cultures that may make people more trusting, more open, those can be factors in scams."

There are also dedicated resources for First Nations people through the ACCC website.

By the Indigenous Affairs Team's Stephanie Boltje

Gloria, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, first heard of the "ding ding" game from her daughter about a year ago.

To play, she would transfer $50 to $150 to different PayID accounts, and while she thought she was winning big, it was just a ruse.

"I was playing a three-game bonus … I won $9,200 and withdrew and submitted and [the website] just took all that money and just gave me to play my own money, $20."

Gloria never saw any cash land in her bank account and she lost access to the site.

"It's a shame job," the 60-year-old said.

Gambling scams, known as "scambling" or "ding ding", are having a "catastrophic" impact on First Nations communities, financial counsellors told the ABC.

They said people signing up to illegal pokies and casino sites in the hope of banking big wins are unknowingly being scammed and embroiled in "micro money laundering".

Players are enticed by free credits and then asked to make regular transfers of cash to a PayID via phone numbers or emails, despite there being little chance of winning.

Casino and blackjack sites are illegal under Australian law so there are no protections for players, and financial intelligence agency AUSTRAC warned if players pay via PayID, the website is "almost certainly a scam".

AUSTRAC acting CEO John Moss said scambling had rapidly evolved into a "sophisticated and pervasive financial crime threat".

Counsellors told the ABC these sites were "highly addictive" and sent spam messages to keep the player engaged.

CatholicCare NT's Kelly Gulliver said she had never seen such devastation from one type of scam in her 25 years working in the sector.

"At first, there is a little bit of incentive [for the player where] they might get some small wins and there are some incentives like free spins if they refer friends and family," she said.

"They are impacted by the false pretence that there is an opportunity for them to win, and they don't really know that it is illegal."

Ms Gulliver first noticed the trend among clients who needed help applying for no-interest loans or emergency relief for food.

When she assessed their bank statements, she saw regular PayID payments of small amounts of money.

"A year ago we saw the odd bank account with these patterns of transactions, [but] now in some communities it's almost maybe 80–90 per cent of people that we support," she said.

"It is absolutely scary … the impacts of it are catastrophic."

While her analysis is ongoing, she has calculated more than 80 areas in the NT that are impacted.

"It's definitely predatory and unethical, so they're coming up on their social media feeds, they're getting messages through WhatsApp, and really we're not seeing any other communities or groups impacted by this yet."

Queensland-based Indigenous Consumer Assistance Network's financial counsellor Alex Price-Busch said he noticed the uptick in users after COVID-19.

"One of the worst examples was a client who received a redress payment and in a mixture of them depositing money onto the site, as well as the access that the site had to their bank, essentially their entire redress payment was siphoned out," the First Nations man said.

"You have people putting in significant amounts of money to chase a win and even if they get that, they might not be able to withdraw it, which doubles the pain and frustration they are already experiencing."

Financial Counselling Australia (FCA) said the scam was "spreading like wildfire" among mob in the NT, WA, NSW and QLD.

"It's definitely one of the worst scams I've ever seen … people are losing hundreds of dollars every day," she said.

"We know that they're not only just losing money, but there's the challenges and the problems in the community around family and domestic violence when there's not enough money to pay bills."

Lynda Edwards is worried about the pace at which "scambling" is spreading in communities. (Supplied: Financial Counselling Australia)

Nearly 800 per cent increase in betting scams

More than 400 First Nations people reported $2.8 million in scam losses to the National Anti-Scam Centre's Scamwatch in the first six months of this year, up more than 18 per cent over the same time last year.That included almost $373,000 lost to betting and sports investment scams, which represented a 797 per cent increase.

Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (ACCC) deputy chair Catriona Lowe told the ABC they were in the process of finding out more about the "emerging scam type".

Financial crime authority AUSTRAC said criminal syndicates or organised crime groups were suspected of being behind illegal online gaming sites.

It warns that it is highly unlikely that authorities in Australia will be able to recover lost funds through these sites.

AUSTRAC's Dr Moss said the authority's Fintel Alliance had identified multiple cases where players in remote and Indigenous communities inadvertently became "money mules" for organised crime groups.

Banks often responded by freezing the person's bank accounts, CatholicCare NT's Kelly Gulliver said, leaving them without money for food and essentials.

Lynda Edwards, a descendant of the Wangkumara people of far west NSW, said they have heard people were handing over banking details for money.

Gloria's bank account was suspended and now she is warning her family not to play or risk losing access to their money.

"I saw different people named on my internet banking," the retiree said.

"Tell them to stop playing ding ding, they just waste a lot of money."

What is being done to clamp down on this scambling?

Advocates want safeguards for the banking customers, as well as a coordinated approach from authorities to tackle the crime, including better data."It is millions of dollars that people are potentially losing and there is not enough protection in place to ensure that they are not at risk," ICAN's Alex Price-Busch said.

ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe said the National Anti-Scam Centre was prioritising the identification of scam gambling websites to refer them for take-down.

"Through close collaboration with banks and digital platforms, we focus on preventing scam contact, stopping interactions that are already underway, and blocking payments before funds are lost."

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) publishes legitimate gambling operators, as well as those that have been banned.

Since 2017, more than 1,290 websites have been blocked, including 270 websites in the past year.

ACMA said if people accessed those blocked sites, they would receive a warning message.

The Australian Banking Association told the Indigenous Affairs Team that "some banks are already undertaking consumer awareness initiatives to help people identify the risks".

"Banks will pursue further discussions with consumer representatives, including whether new provisions to require the taking down of fraudulent apps are required."

What should you do if you are duped?

CatholicCare NT's Kelly Gulliver advises people to contact their banks, put a stop to communication and block the numbers and the site, as well as telling friends and family.The ACCC urges victims to stop, check and protect, and if people are victims, to report to Scamwatch and seek assistance from the cyber support service IDCARE.

Scambling is not the only scam targeting Indigenous communities.

In the first six months of 2025, nearly a million dollars was lost by First Nations people through investment scams such as fake term deposits.

Shopping scams accounted for 162 Indigenous people's losses — a nearly 60 per cent increase on last year, while there was a 116 per cent increase to jobs scams.

"Where there are language barriers, or indeed cultures that may make people more trusting, more open, those can be factors in scams."

There are also dedicated resources for First Nations people through the ACCC website.

By the Indigenous Affairs Team's Stephanie Boltje