Pharmacies are running dry! And families are already fighting over the last bottles of this medication

By

Maan

- Replies 0

A mother found herself in a shouting match with a stranger over the last bottle of ADHD medication at a local pharmacy.

She had been ringing her doctor in a panic, trying to secure a prescription before the bottle was gone.

But the real shock came with a gut-punching thought: ‘How did we come to this?’

Families across Australia were still grappling with a national shortage of ADHD medications, with experts warning the crisis could drag on until the end of 2026.

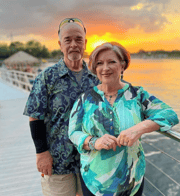

Psychologist Jane McFadden, who also hosted one of the country’s largest mental health podcasts, ADHD Mums, said the situation had left families ‘completely let down’.

McFadden was diagnosed with ADHD at the age of 36, and her three children—now all under 10—were diagnosed soon after.

‘It’s mind-blowing. You realise you have been white-knuckling through life,’ she said.

She said treatment helped her feel in control of her life, improved her parenting, and strengthened her relationship with her husband.

Her children also experienced a breakthrough once they finally received their prescriptions—after a two-year wait and thousands of dollars in medical costs.

But that progress quickly unravelled when the medication shortage hit, leaving McFadden scrambling to find alternatives.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration listed numerous medications as being in shortage, including Concerta modified-release tablets, Teva-XR, Ritalin LA and Rubifen LA capsules, and Ritalin 10mg immediate-release tablets.

McFadden said she sometimes spent her weekends calling up to 30 pharmacies before embarking on long drives in hopes of securing medication.

On one occasion, the last bottle was sold just before she arrived.

Another time, she found herself arguing with a father over the same final bottle while trying to reach her doctor for an updated script.

‘He didn’t seem like a bad person or anything, he was just desperate like I was,’ she said.

‘It was astounding—here we were fighting over a bottle of medicine, and I remember thinking, how did we come to this?’

She questioned why there had been no action to manufacture ADHD medication locally and called for a long-term national solution.

The federal government recently expanded ADHD diagnosis powers to GPs, a move welcomed by advocates like McFadden.

However, experts warned the change would not solve the deeper issues at play.

Psychologist and Macquarie Health Collective chief executive Tanya Forster said while the rule change helped accessibility—especially for people in rural areas—it created new challenges.

Forster said Australia was already facing a GP shortage, and this added responsibility could overwhelm the system.

‘We can’t solve one problem by worsening another,’ she said.

She also noted that more accessible testing would likely lead to more diagnoses, increasing pressure on the already fragile medication supply chain.

‘It will take action from the government to correct the supply chain issue,’ she said.

For families, the wait and uncertainty had become a daily burden.

Forster explained that children diagnosed early and given consistent access to medication were more likely to develop the skills needed to manage ADHD as adults.

For McFadden’s family, the shortage had taken a visible toll.

She said her children had struggled with the inconsistency, which often meant switching medications that didn’t suit their needs.

‘You’re told, “go on another type of medication”—it doesn’t really work that way for ADHD,’ she said.

She explained that an unstable supply meant her kids were ‘changing their brain function every day’, creating confusion at home and in the classroom.

McFadden believed part of the issue stemmed from a lingering stigma—some still viewed ADHD medication as optional rather than essential.

And despite her advocacy reaching more than a million Australians annually, she said the government still hadn’t listened.

Forster urged families not to self-medicate or share prescriptions in desperation.

‘If we are self-medicating, sharing, or rationing medications, there are risks involved,’ she said.

‘These are regulated medicines for a reason.’

The TGA’s full advice on ADHD medication shortages remained available online.

If you’ve ever felt the frustration of chasing down a script, only to be told it’s out of stock, you’re not alone.

The ADHD medication shortage is just one part of a much bigger issue affecting access to essential medicines.

Another report shines a light on how widespread—and quietly devastating—these shortages have become.

Read more: ‘Extremely difficult to source’: The hidden health crisis gripping Australian pharmacies

What would you do if your child’s daily wellbeing depended on a medication that might not be available tomorrow?

She had been ringing her doctor in a panic, trying to secure a prescription before the bottle was gone.

But the real shock came with a gut-punching thought: ‘How did we come to this?’

Families across Australia were still grappling with a national shortage of ADHD medications, with experts warning the crisis could drag on until the end of 2026.

Psychologist Jane McFadden, who also hosted one of the country’s largest mental health podcasts, ADHD Mums, said the situation had left families ‘completely let down’.

McFadden was diagnosed with ADHD at the age of 36, and her three children—now all under 10—were diagnosed soon after.

‘It’s mind-blowing. You realise you have been white-knuckling through life,’ she said.

She said treatment helped her feel in control of her life, improved her parenting, and strengthened her relationship with her husband.

Her children also experienced a breakthrough once they finally received their prescriptions—after a two-year wait and thousands of dollars in medical costs.

But that progress quickly unravelled when the medication shortage hit, leaving McFadden scrambling to find alternatives.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration listed numerous medications as being in shortage, including Concerta modified-release tablets, Teva-XR, Ritalin LA and Rubifen LA capsules, and Ritalin 10mg immediate-release tablets.

McFadden said she sometimes spent her weekends calling up to 30 pharmacies before embarking on long drives in hopes of securing medication.

On one occasion, the last bottle was sold just before she arrived.

Another time, she found herself arguing with a father over the same final bottle while trying to reach her doctor for an updated script.

‘He didn’t seem like a bad person or anything, he was just desperate like I was,’ she said.

‘It was astounding—here we were fighting over a bottle of medicine, and I remember thinking, how did we come to this?’

She questioned why there had been no action to manufacture ADHD medication locally and called for a long-term national solution.

The federal government recently expanded ADHD diagnosis powers to GPs, a move welcomed by advocates like McFadden.

However, experts warned the change would not solve the deeper issues at play.

Psychologist and Macquarie Health Collective chief executive Tanya Forster said while the rule change helped accessibility—especially for people in rural areas—it created new challenges.

Forster said Australia was already facing a GP shortage, and this added responsibility could overwhelm the system.

‘We can’t solve one problem by worsening another,’ she said.

She also noted that more accessible testing would likely lead to more diagnoses, increasing pressure on the already fragile medication supply chain.

‘It will take action from the government to correct the supply chain issue,’ she said.

For families, the wait and uncertainty had become a daily burden.

Forster explained that children diagnosed early and given consistent access to medication were more likely to develop the skills needed to manage ADHD as adults.

For McFadden’s family, the shortage had taken a visible toll.

She said her children had struggled with the inconsistency, which often meant switching medications that didn’t suit their needs.

‘You’re told, “go on another type of medication”—it doesn’t really work that way for ADHD,’ she said.

She explained that an unstable supply meant her kids were ‘changing their brain function every day’, creating confusion at home and in the classroom.

McFadden believed part of the issue stemmed from a lingering stigma—some still viewed ADHD medication as optional rather than essential.

And despite her advocacy reaching more than a million Australians annually, she said the government still hadn’t listened.

Forster urged families not to self-medicate or share prescriptions in desperation.

‘If we are self-medicating, sharing, or rationing medications, there are risks involved,’ she said.

‘These are regulated medicines for a reason.’

The TGA’s full advice on ADHD medication shortages remained available online.

If you’ve ever felt the frustration of chasing down a script, only to be told it’s out of stock, you’re not alone.

The ADHD medication shortage is just one part of a much bigger issue affecting access to essential medicines.

Another report shines a light on how widespread—and quietly devastating—these shortages have become.

Read more: ‘Extremely difficult to source’: The hidden health crisis gripping Australian pharmacies

Key Takeaways

- ADHD medication shortages were expected to last until late 2026.

- Parents reported spending hours contacting pharmacies and travelling long distances.

- Experts warned that new GP rules may increase diagnoses but not solve supply issues.

- Advocates called for domestic manufacturing and a long-term government strategy.

What would you do if your child’s daily wellbeing depended on a medication that might not be available tomorrow?