More than just MasterChef: a brief history of Australian cookery competitions

- Replies 8

Australians were involved in competitive cookery long before MasterChef.

The earliest of Australia’s cooking competitions were at agricultural shows. In 1910, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW hosted its first competition for “perishable foods” at the Royal Easter Show.

Along with pastry and pickles, competitors could also be judged on their calf’s foot jelly.

By the 1920s, the cookery category at the Easter Show had been firmly established. It was purely the preserve of women. Men were prohibited from entering and wouldn’t be allowed to enter until after the second world war.

Women living in NSW and the ACT also entered their wares in the Country Women’s Association’s The Land Cookery Competition. Starting in 1949, the competition judged women on their ability to bake classics such as fruit cake, butter cake and lamingtons, offering modest prize money to the winners. It is still running today.

These competitions are grounded in a history of cooking which saw women as “cooks” and men as “chefs”. Women were amateurs working in the home, while men worked in professional kitchens. This phenomenon continues today.

Cookery competitions allowed women to receive recognition for their often-overlooked hard work and skill. Contestants were encouraged to break out of their comfort zones, to be creative, innovate and impress.

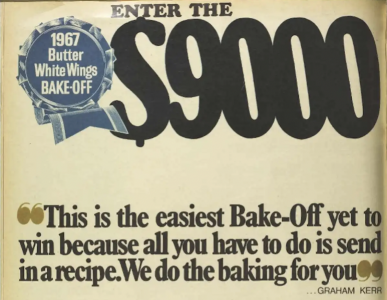

Perhaps the most extravagant of these competitions was the Butter-White Wings Bake-Off, which ran from 1963 to 1970. The competition pitted Australia’s best home bakers against each other in a variety of categories, including cakes, desserts, main courses and “busy lady recipes”.

Entering their written recipes, contestants competed at state level for a chance to win a trip to the national final where they would cook for illustrious judges.

Thousands competed at the state level of these competitions, and one from each state and territory would go on to the final. These were held in either Sydney or Melbourne in front of live audiences, usually in the middle of a department store.

The 1970 final was televised, with the Weekly estimating two million viewerswould watch the proceedings.

It was Australia’s first televised cooking competition.

The choice of judges also offers us a glimpse of the glamour associated with the competitions as well as the continued gendered expectations surrounding cookery. A slew of early “celebrity chefs” were flown in from exotic, international destinations to judge the competition – including the Galloping Gourmet himself, Graham Kerr.

These celebrity chefs judged the main course section; the overtly feminine baking sections were judged primarily by women.

It was in the cake section that contestants really went above and beyond, both in the recipes themselves and in their names. In 1968, prize-winning recipes included “Golden Crown Dessert”, “Marshmallow-Cherry Cake”, “Chocolate Gold Layer Cake” and “Peach Kuchen”.

Peach Kuchen, which won the “Busy Lady” section, was made with a packet of White Wings cake mix, a tin of peaches and some sour cream. The Bake-Off helped to popularise (and sell!) boxed cake mixes: even the “busy woman” could create delicious cakes deserving of accolades.

Her prize-winning menu included oysters in pastry cases, ballotine of duckling with baby vegetables and a red wine jus, mango sorbet and almond petits fours.

In a recent interview, Love reflected that her menu drew on the concepts of nouvelle cuisine, which was popular at the time. It was an ambitious menu for a home cook – however Love declared that she didn’t think it would do very well if she went on MasterChef today.

Australian cooking has come a long way – competitions are no longer for the busy home cook. Shutterstock

Her menu demonstrates the dizzying progression of Australian food over the past 40 years.

Cookery competitions like those held in the Weekly gradually disappeared, replaced instead by competitions on television, which have grown in popularity over the last two decades.

Like the magazine cookery competitions of the past, where contestants were inventive and used new and exciting ingredients, television competitions have also proved important for introducing the Australian palate to innovative cooking techniques and exotic ingredients.

Our ongoing fascination with cooking competition shows such as MasterChef reflects the prestige still on offer for those ambitious contestants who enter them, as well as the cultural importance of food.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Lauren Samuelsson, Honorary Fellow, University of Wollongong

The earliest of Australia’s cooking competitions were at agricultural shows. In 1910, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW hosted its first competition for “perishable foods” at the Royal Easter Show.

Along with pastry and pickles, competitors could also be judged on their calf’s foot jelly.

By the 1920s, the cookery category at the Easter Show had been firmly established. It was purely the preserve of women. Men were prohibited from entering and wouldn’t be allowed to enter until after the second world war.

Women living in NSW and the ACT also entered their wares in the Country Women’s Association’s The Land Cookery Competition. Starting in 1949, the competition judged women on their ability to bake classics such as fruit cake, butter cake and lamingtons, offering modest prize money to the winners. It is still running today.

These competitions are grounded in a history of cooking which saw women as “cooks” and men as “chefs”. Women were amateurs working in the home, while men worked in professional kitchens. This phenomenon continues today.

Cookery competitions allowed women to receive recognition for their often-overlooked hard work and skill. Contestants were encouraged to break out of their comfort zones, to be creative, innovate and impress.

Magazine cookery competitions

With women as their key demographic, it is little wonder that, by the 1960s, women’s magazines such as the Australian Women’s Weekly began hosting large-scale cookery competitions open to readers around the country.Perhaps the most extravagant of these competitions was the Butter-White Wings Bake-Off, which ran from 1963 to 1970. The competition pitted Australia’s best home bakers against each other in a variety of categories, including cakes, desserts, main courses and “busy lady recipes”.

Entering their written recipes, contestants competed at state level for a chance to win a trip to the national final where they would cook for illustrious judges.

Thousands competed at the state level of these competitions, and one from each state and territory would go on to the final. These were held in either Sydney or Melbourne in front of live audiences, usually in the middle of a department store.

The 1970 final was televised, with the Weekly estimating two million viewerswould watch the proceedings.

It was Australia’s first televised cooking competition.

Marketing and celebrities

Just as MasterChef is sponsored by advertisers, the cookery competitions hosted in the Weekly proved to be lucrative marketing opportunities for a variety of sponsors. The prizes, provided by sponsors such as Breville and QANTAS, included cash, fur coats, appliances, cars and overseas holidays.The choice of judges also offers us a glimpse of the glamour associated with the competitions as well as the continued gendered expectations surrounding cookery. A slew of early “celebrity chefs” were flown in from exotic, international destinations to judge the competition – including the Galloping Gourmet himself, Graham Kerr.

These celebrity chefs judged the main course section; the overtly feminine baking sections were judged primarily by women.

It was in the cake section that contestants really went above and beyond, both in the recipes themselves and in their names. In 1968, prize-winning recipes included “Golden Crown Dessert”, “Marshmallow-Cherry Cake”, “Chocolate Gold Layer Cake” and “Peach Kuchen”.

Peach Kuchen, which won the “Busy Lady” section, was made with a packet of White Wings cake mix, a tin of peaches and some sour cream. The Bake-Off helped to popularise (and sell!) boxed cake mixes: even the “busy woman” could create delicious cakes deserving of accolades.

A dizzying progression

The last Butter-White Wings Bake-Off was held in 1970, but the magazine kept hosting cooking competitions. In 1980, Elizabeth Love was crowned “Best Cook in Australia.”Her prize-winning menu included oysters in pastry cases, ballotine of duckling with baby vegetables and a red wine jus, mango sorbet and almond petits fours.

In a recent interview, Love reflected that her menu drew on the concepts of nouvelle cuisine, which was popular at the time. It was an ambitious menu for a home cook – however Love declared that she didn’t think it would do very well if she went on MasterChef today.

Australian cooking has come a long way – competitions are no longer for the busy home cook. Shutterstock

Her menu demonstrates the dizzying progression of Australian food over the past 40 years.

Cookery competitions like those held in the Weekly gradually disappeared, replaced instead by competitions on television, which have grown in popularity over the last two decades.

Like the magazine cookery competitions of the past, where contestants were inventive and used new and exciting ingredients, television competitions have also proved important for introducing the Australian palate to innovative cooking techniques and exotic ingredients.

Our ongoing fascination with cooking competition shows such as MasterChef reflects the prestige still on offer for those ambitious contestants who enter them, as well as the cultural importance of food.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Lauren Samuelsson, Honorary Fellow, University of Wollongong