Lost inheritance? Why millions in unclaimed estates end up with the government

- Replies 20

Can you be sure the people you leave your estate to will actually get it?

Every year, millions of dollars meant to be passed on to loved ones never reach their beneficiaries – instead, this money winds up in government coffers. It sounds unbelievable, but unclaimed deceased estates are more common than you might think.

In one recent case, a Queensland estate worth $2 million had no heir to claim it, so the funds were handed to the state treasury. For older Australians, it’s a cautionary tale: without careful estate planning, your life’s savings could become part of this hidden windfall for the government.

In this editorial, we’ll explore how unclaimed estates are handled in Australia, why so many estates go unclaimed, and what can be done to ensure your legacy ends up in the right hands. We’ll look at the laws across different states, share notable examples, and offer some friendly tips on wills and estate planning.

After all, you’ve worked hard for what you have – the last thing you’d want is for it to vanish into government accounts.

Lawyers sometimes call this situation bona vacantia, meaning “ownerless goods”. It ensures that money, property, and other assets don’t just lie in limbo forever – they’re taken over by the government when no rightful owner can be found.

To be clear, the government doesn’t swoop in immediately. Intestacy laws first dictate a strict order of eligible relatives who can inherit if there’s no will. The hierarchy starts with your spouse and children, then parents, then siblings, and extends outward to nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, and first cousins.

If you have even one relative in that range, your estate should eventually go to them under the law. But if no living relative closer than a first cousin can be located, your estate is deemed ownerless and at that point it falls to the state.

These situations are relatively rare – but they do happen, especially to people who leave no will or whose family ties are distant. Often the Public Trustee (or equivalent body in each state) will conduct exhaustive searches for any next of kin. Genealogists may be hired to trace family trees in an effort to find someone, even if it’s a long-lost cousin.

Only when all efforts fail to find a living beneficiary will the state government take control of the estate. And even then, it’s not immediate – the estate is usually held in trust for a number of years first, just in case a legitimate heir turns up late in the game.

Despite these differences, one thing is common: no government actually wants to claim someone’s inheritance. Officials will tell you their priority is to find the rightful owners.

“We do the utmost within our powers to find beneficiaries of deceased estates before transferring funds to Treasury,” says Queensland Public Trustee Samay Zhouand.

State trustees maintain online databases and unclaimed money registers where people can search if they’re entitled to any unclaimed funds. And even once money has gone to the state, it’s often still possible for a beneficiary to claim it (indefinitely in many cases, or at least with a long window).

In NSW, for example, you effectively have up to 12 years to come forward and claim an estate before it’s locked in. So the government taking your money isn’t the foregone conclusion some fear – it’s more of a last resort when no family, no will, and no one with a valid claim materializes.

Not Having a Will: Perhaps the biggest reason is simply that people don’t write a will. Astonishingly, around 60% of Australian adults have not made a will at all. Many Australians die without any formal estate plan – sometimes because they keep putting it off, sometimes because they feel they “don’t have much to leave,” and sometimes due to unexpected illness or accidents catching them before they ever get to it.

If you pass away intestate, you’re automatically relying on that predefined next-of-kin hierarchy. And if you also happen to have no close living family, your estate is at high risk of going unclaimed by anyone except the government.

Outdated or Invalid Wills: Even among those who do have wills, problems can arise if the will isn’t kept up to date. Life is full of change – beneficiaries might predecease you, family circumstances evolve, marriages and divorces happen (which can even invalidate a will in some states). An old will might name people who are no longer around. If, say, you left everything to a sibling who died before you, and you never updated that document, you could inadvertently create an unclaimed estate scenario.

Your will could fail (fully or partly), and your assets would then be distributed by the intestacy laws (which might end up pointing to no one living). It’s easy to put the will in the bottom drawer and forget about it, but experts say it’s wise to review your will every two to three years or whenever you go through a major life change.

Keeping your will current greatly reduces the odds of surprises that leave assets with no rightful taker.

Estranged or Unaware Family: In some cases, people do have relatives, but they’ve lost touch or become estranged. The relatives might not even know the person passed away, or know they were related closely enough to stake a claim. Authorities do try to find next of kin, but they can only search so far. If you have a very small family or have cut off contact with them, it’s possible no one steps forward when you’re gone.

One estate lawyer noted that in her 25-year career she saw a few cases where professional genealogists had to be engaged to piece together a family tree – these cases stick in memory because they were “so difficult and unnecessarily complex and expensive”.

Now, four or five cases over decades isn’t huge, but those represent instances where nobody was immediately around to claim the estate – a clear recipe for an unclaimed estate if the searches had failed.

Believing “The Government Will Find My Heirs”: Some people mistakenly assume that if they die, the government will diligently locate any blood relative no matter how distant. In reality, the law draws the line at first cousins in most places. That means if you don’t have at least a cousin or closer, the government isn’t going to play detective beyond that. They’re not hunting for great-great-nephews or second cousins twice removed.

So if you have very distant kin or none at all, and you haven’t specified any beneficiaries in a will, your estate is likely to be unclaimed. Even close relatives can be missed if they’re unknown to authorities (for example, if you have a child out of touch or overseas that nobody knows about, it’s possible they won’t be found in time).

Traps in Estate Planning: There are some subtle traps that can lead to assets going unclaimed. For instance, if you name a beneficiary for your superannuation or life insurance but they predecease you and you didn’t update the nomination, those funds might revert to your estate and follow intestacy rules (again raising the risk of no claimant if no family).

Or if you stash important documents (like your will) in too secret a spot without telling anyone, your family might not find your will, leading them to think you died intestate even if you didn’t – potentially sending your estate down the wrong path. Administrative errors or poor communication can result in money being “lost” until it ends up in a state unclaimed money register.

All these factors contribute to the surprising amount of money sitting with government waiting to be claimed. For example, Revenue NSW – which handles unclaimed money in New South Wales – is holding over $234 million in unclaimed funds owed to people, even after record amounts have been claimed back each year. That figure includes not just deceased estates but also things like old bank accounts and unpresented cheques, yet it gives a sense of scale. It’s not a trivial sum.

When you hear about “millions go to government, not beneficiaries,” it’s often due to the factors above aligning in an unfortunate way.

So, why do so many estates go unclaimed? Because too many people don’t take steps to avoid it. As one legal expert put it: If people make a will and they don’t have family members, they can at least direct their money to friends or to charities where that money could actually do some good, instead of it ending up with the government.

In short: planning and communication are key. Which brings us to our next section – what can be done to reduce the chances of your estate becoming one of those unclaimed millions.

Make a Will (and Make It Legal): First and foremost, create a will if you haven’t already. It doesn’t have to be hard or expensive – a basic will for a straightforward estate isn’t a massive undertaking. You can engage a solicitor or use a will-writing service; many Public Trustee offices offer free or low-cost will drafting for seniors. Will kits from post offices or online are an option too, though be cautious with DIY – even a small mistake in wording can cause issues.

The critical thing is that a will clearly states who gets what when you’re gone. That way, even if you have no blood relatives, you can name a friend, a godchild, a charity, or anyone you care about to inherit your assets. This completely bypasses the scenario of the state deciding for you.

As one trustee advertisement wisely put it: “If you don’t have a will, the government has one for you” – and trust us, you might not like its terms. So take the time to put your wishes on paper with the proper legal formalities.

Update Your Will Regularly: Making a will is step one; keeping it up to date is step two. Revisit your will every few years, and especially after any big life event (marriage, divorce, the birth of a grandchild, the loss of a beneficiary, etc.).

Circumstances change – your will should change with them. If a person you named in your will has passed away, choose a new beneficiary for that share. If you’ve acquired new assets, make sure they’re covered. And be mindful of any quirks in your state’s laws (for example, in some states like SA, a marriage or divorce can revoke parts of your will automatically).

An up-to-date will ensures that no portion of your estate is left in limbo. It’s also wise to include contingent beneficiaries – e.g. “I leave my estate to my sister, but if she predeceases me, then to my niece.” This kind of backup plan can prevent an unintended intestacy.

Communicate Your Wishes: Talk to your family or trusted friends about your plans. It might feel like a morbid topic, but letting people know you have a will and where it’s kept is important. If no one even knows a will exists, they might assume you died intestate and not look for it, leading to unnecessary legal hurdles. Make sure your executor (the person you appoint to administer your will) has a copy or knows how to access it.

If you have no close family, consider informing the main beneficiaries you’ve named (be it a friend or a charity) so they’re aware. Open communication can also prevent disputes and ensure that when the time comes, someone responsible is ready to step in and carry out your wishes.

Organize Your Estate Information: One reason money goes unclaimed is simply that people can’t find it. Keep a list of your assets – bank accounts, insurance policies, superannuation accounts, property titles, etc. – and update it as needed. You don’t necessarily have to share this list widely, but make sure your executor or a trusted person knows where to find it (for example, “all my important papers are in this filing cabinet” or “here’s a USB drive with my financial info”).

Don’t forget digital assets and online accounts. If you’ve got shares, or perhaps some money in an old bank account, include those details. When everything is organized, it’s far less likely something will slip through the cracks and end up on the unclaimed money register later.

Consider All Your Potential Beneficiaries: If you have a small family or none at all, think about who you would like to benefit from your estate. It could be extended relatives you do know (even if the law wouldn’t reach them automatically). It could be a family friend, or someone who cared for you, or a charitable cause close to your heart.

You have the power to name them in your will. By doing so, you ensure your money goes to a meaningful place rather than becoming “government revenue.” Remember, intestacy law wouldn’t give a cent to a friend or a charity – but your will can. As estate planners often say, a will is your voice after death. Use that voice to direct your legacy where you truly want it to go.

Seek Professional Advice if Needed: If your situation is at all complex – say, you’re unsure how to provide for a relative with special needs, or you’re unmarried but have a long-term partner, or you want to set up a trust – consider getting advice from a solicitor or estate planner.

Professionals can help ensure your documents are legally sound and that no part of your estate gets overlooked. They can also advise on things like appointing substitute executors, handling superannuation death nominations, and other finer points. Investing a little in good advice now can save your family a lot of trouble later, and it further guarantees that nothing of yours goes unclaimed or misdirected.

Finally, one more consideration: if you think you might be entitled to someone else’s unclaimed estate (perhaps a relative who passed away), you can be proactive. Each state maintains resources to search for unclaimed estates or money. For example, NSW has an online Unclaimed Money Register, and other states have similar databases.

A quick search might reveal if you or your late relatives have money waiting. It’s worth a try – you might uncover a lost bank account or an inheritance you didn’t know about.

As we’ve seen, the laws are there to catch you if you don’t plan (up to a point), but they’re a blunt instrument and can yield some unfortunate outcomes. The power is in your hands to fine-tune what happens when you’re not around.

So, take a moment to reflect: What steps will you take now to make sure your legacy ends up where you want it, and not among the unclaimed millions?

Every year, millions of dollars meant to be passed on to loved ones never reach their beneficiaries – instead, this money winds up in government coffers. It sounds unbelievable, but unclaimed deceased estates are more common than you might think.

In one recent case, a Queensland estate worth $2 million had no heir to claim it, so the funds were handed to the state treasury. For older Australians, it’s a cautionary tale: without careful estate planning, your life’s savings could become part of this hidden windfall for the government.

In this editorial, we’ll explore how unclaimed estates are handled in Australia, why so many estates go unclaimed, and what can be done to ensure your legacy ends up in the right hands. We’ll look at the laws across different states, share notable examples, and offer some friendly tips on wills and estate planning.

After all, you’ve worked hard for what you have – the last thing you’d want is for it to vanish into government accounts.

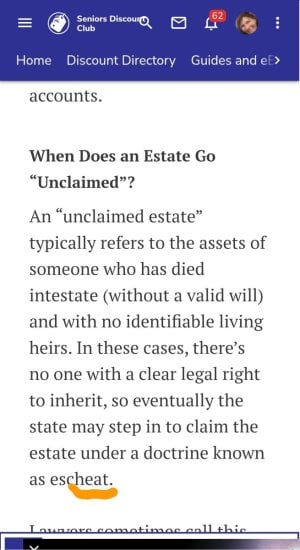

When Does an Estate Go “Unclaimed”?

An “unclaimed estate” typically refers to the assets of someone who has died intestate (without a valid will) and with no identifiable living heirs. In these cases, there’s no one with a clear legal right to inherit, so eventually the state may step in to claim the estate under a doctrine known as escheat.Lawyers sometimes call this situation bona vacantia, meaning “ownerless goods”. It ensures that money, property, and other assets don’t just lie in limbo forever – they’re taken over by the government when no rightful owner can be found.

To be clear, the government doesn’t swoop in immediately. Intestacy laws first dictate a strict order of eligible relatives who can inherit if there’s no will. The hierarchy starts with your spouse and children, then parents, then siblings, and extends outward to nieces and nephews, aunts and uncles, and first cousins.

If you have even one relative in that range, your estate should eventually go to them under the law. But if no living relative closer than a first cousin can be located, your estate is deemed ownerless and at that point it falls to the state.

These situations are relatively rare – but they do happen, especially to people who leave no will or whose family ties are distant. Often the Public Trustee (or equivalent body in each state) will conduct exhaustive searches for any next of kin. Genealogists may be hired to trace family trees in an effort to find someone, even if it’s a long-lost cousin.

Only when all efforts fail to find a living beneficiary will the state government take control of the estate. And even then, it’s not immediate – the estate is usually held in trust for a number of years first, just in case a legitimate heir turns up late in the game.

How Unclaimed Estates Are Handled (State by State)

Australia doesn’t have one single rule for unclaimed estates; each state and territory has its own laws and procedures. The fundamental principle is the same – if no rightful heir can be found, the state government becomes the beneficiary – but the timeline and details differ across jurisdictions. Here’s how it generally works:- New South Wales (NSW): In NSW, the NSW Trustee & Guardian will hold an intestate estate while searching for relatives. If no claim is made within 12 years, the estate is permanently transferred to the state’s coffers (the NSW Consolidated Fund). In other words, the government formally absorbs the assets after 12 years of no one coming forward. (Even then, if a long-lost relative shows up after that, they can attempt to reclaim the estate – but by then it’s legally complicated and far from guaranteed.)

- Queensland: Queensland’s Public Trustee takes a slightly different approach. The Public Trustee will hold funds for up to six years while trying to track down beneficiaries. If that search comes up empty, the money is transferred to Queensland Treasury and treated as consolidated revenue. However – and importantly – Queensland allows claims to be made at any time afterward. As Public Trustee Samay Zhouand explains, “Should a beneficiary emerge in the future, those funds remain available without time limit for those beneficiaries to claim.” In other words, even after the estate’s value has gone into government accounts, it can be paid out to a rightful heir who later proves their entitlement. Queensland recently revealed that between 2020 and 2024 it had to transfer $2.95 million from 10 estates to the Treasury because no beneficiaries could be found – most of it from one single $2 million estate.

- Victoria: If no next of kin can be found up to the degree of first cousins in Victoria, the estate is declared bona vacantia and the State Revenue Office (on behalf of the state) takes ownership. Victoria’s laws have an interesting twist: the Minister for Finance has discretion under the Financial Management Act to provide the assets to someone who might have a moral claim. For example, the Minister could decide to give part of an unclaimed estate to a person who was financially dependent on the deceased or to a charity the deceased supported, if it seems likely the deceased “might reasonably have made provision for [them] in their will.” This kind of ex-gratia distribution isn’t automatic – someone with a claim must apply through the Crown Solicitor and make a case to the Attorney-General explaining why they deserve a share of the estate. It’s a way to prevent truly unjust outcomes, like a caregiver or close friend being left with nothing while the money goes to the government. But such cases are quite rare.

- Other States and Territories: Broadly, other jurisdictions follow the same pattern of transferring ownerless estates to the government, with some variations. In South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania, the Northern Territory, and the ACT, intestacy laws also stop at a certain degree of kinship (usually first cousins). If no one in that circle is found, the estate escheats to the Crown (i.e. to the state). The timing and process can vary – for instance, some might hold the assets for a set period (like NSW’s 12 years) before closing the books. Western Australia has a unique provision for Indigenous people: under the Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority Act 1972 (WA), if an Aboriginal person dies intestate with no eligible kin, the estate (after any claims) is eventually vested in the Aboriginal Affairs Planning Authority “for the benefit of persons of Aboriginal descent.” In other words, instead of going into general state revenue, an unclaimed Indigenous estate in WA is directed to a fund to benefit the Indigenous community. Every state also empowers a Public Trustee or official administrator to manage the estate in the interim and to pay out any valid claims that surface later (for example, if a relative is found or someone proves a dependency).

Despite these differences, one thing is common: no government actually wants to claim someone’s inheritance. Officials will tell you their priority is to find the rightful owners.

“We do the utmost within our powers to find beneficiaries of deceased estates before transferring funds to Treasury,” says Queensland Public Trustee Samay Zhouand.

State trustees maintain online databases and unclaimed money registers where people can search if they’re entitled to any unclaimed funds. And even once money has gone to the state, it’s often still possible for a beneficiary to claim it (indefinitely in many cases, or at least with a long window).

In NSW, for example, you effectively have up to 12 years to come forward and claim an estate before it’s locked in. So the government taking your money isn’t the foregone conclusion some fear – it’s more of a last resort when no family, no will, and no one with a valid claim materializes.

Why Do So Many Estates Go Unclaimed?

If dying without a next of kin is relatively uncommon, you might wonder: why are there so many unclaimed estates piling up? The truth is, intestacy and unclaimed assets are far from rare. Several factors contribute to the phenomenon of estates ending up unclaimed:Not Having a Will: Perhaps the biggest reason is simply that people don’t write a will. Astonishingly, around 60% of Australian adults have not made a will at all. Many Australians die without any formal estate plan – sometimes because they keep putting it off, sometimes because they feel they “don’t have much to leave,” and sometimes due to unexpected illness or accidents catching them before they ever get to it.

If you pass away intestate, you’re automatically relying on that predefined next-of-kin hierarchy. And if you also happen to have no close living family, your estate is at high risk of going unclaimed by anyone except the government.

Outdated or Invalid Wills: Even among those who do have wills, problems can arise if the will isn’t kept up to date. Life is full of change – beneficiaries might predecease you, family circumstances evolve, marriages and divorces happen (which can even invalidate a will in some states). An old will might name people who are no longer around. If, say, you left everything to a sibling who died before you, and you never updated that document, you could inadvertently create an unclaimed estate scenario.

Your will could fail (fully or partly), and your assets would then be distributed by the intestacy laws (which might end up pointing to no one living). It’s easy to put the will in the bottom drawer and forget about it, but experts say it’s wise to review your will every two to three years or whenever you go through a major life change.

Keeping your will current greatly reduces the odds of surprises that leave assets with no rightful taker.

Estranged or Unaware Family: In some cases, people do have relatives, but they’ve lost touch or become estranged. The relatives might not even know the person passed away, or know they were related closely enough to stake a claim. Authorities do try to find next of kin, but they can only search so far. If you have a very small family or have cut off contact with them, it’s possible no one steps forward when you’re gone.

One estate lawyer noted that in her 25-year career she saw a few cases where professional genealogists had to be engaged to piece together a family tree – these cases stick in memory because they were “so difficult and unnecessarily complex and expensive”.

Now, four or five cases over decades isn’t huge, but those represent instances where nobody was immediately around to claim the estate – a clear recipe for an unclaimed estate if the searches had failed.

Believing “The Government Will Find My Heirs”: Some people mistakenly assume that if they die, the government will diligently locate any blood relative no matter how distant. In reality, the law draws the line at first cousins in most places. That means if you don’t have at least a cousin or closer, the government isn’t going to play detective beyond that. They’re not hunting for great-great-nephews or second cousins twice removed.

So if you have very distant kin or none at all, and you haven’t specified any beneficiaries in a will, your estate is likely to be unclaimed. Even close relatives can be missed if they’re unknown to authorities (for example, if you have a child out of touch or overseas that nobody knows about, it’s possible they won’t be found in time).

Traps in Estate Planning: There are some subtle traps that can lead to assets going unclaimed. For instance, if you name a beneficiary for your superannuation or life insurance but they predecease you and you didn’t update the nomination, those funds might revert to your estate and follow intestacy rules (again raising the risk of no claimant if no family).

Or if you stash important documents (like your will) in too secret a spot without telling anyone, your family might not find your will, leading them to think you died intestate even if you didn’t – potentially sending your estate down the wrong path. Administrative errors or poor communication can result in money being “lost” until it ends up in a state unclaimed money register.

All these factors contribute to the surprising amount of money sitting with government waiting to be claimed. For example, Revenue NSW – which handles unclaimed money in New South Wales – is holding over $234 million in unclaimed funds owed to people, even after record amounts have been claimed back each year. That figure includes not just deceased estates but also things like old bank accounts and unpresented cheques, yet it gives a sense of scale. It’s not a trivial sum.

When you hear about “millions go to government, not beneficiaries,” it’s often due to the factors above aligning in an unfortunate way.

So, why do so many estates go unclaimed? Because too many people don’t take steps to avoid it. As one legal expert put it: If people make a will and they don’t have family members, they can at least direct their money to friends or to charities where that money could actually do some good, instead of it ending up with the government.

In short: planning and communication are key. Which brings us to our next section – what can be done to reduce the chances of your estate becoming one of those unclaimed millions.

Keeping Your Legacy in the Right Hands: Tips for Wills and Estate Planning

The good news is that avoiding the fate of an unclaimed estate is entirely within your control. It simply requires a bit of planning and foresight. Here are some practical tips and considerations for older Australians (and indeed, for adults of any age) to make sure your estate goes where you want it to:Make a Will (and Make It Legal): First and foremost, create a will if you haven’t already. It doesn’t have to be hard or expensive – a basic will for a straightforward estate isn’t a massive undertaking. You can engage a solicitor or use a will-writing service; many Public Trustee offices offer free or low-cost will drafting for seniors. Will kits from post offices or online are an option too, though be cautious with DIY – even a small mistake in wording can cause issues.

The critical thing is that a will clearly states who gets what when you’re gone. That way, even if you have no blood relatives, you can name a friend, a godchild, a charity, or anyone you care about to inherit your assets. This completely bypasses the scenario of the state deciding for you.

As one trustee advertisement wisely put it: “If you don’t have a will, the government has one for you” – and trust us, you might not like its terms. So take the time to put your wishes on paper with the proper legal formalities.

Update Your Will Regularly: Making a will is step one; keeping it up to date is step two. Revisit your will every few years, and especially after any big life event (marriage, divorce, the birth of a grandchild, the loss of a beneficiary, etc.).

Circumstances change – your will should change with them. If a person you named in your will has passed away, choose a new beneficiary for that share. If you’ve acquired new assets, make sure they’re covered. And be mindful of any quirks in your state’s laws (for example, in some states like SA, a marriage or divorce can revoke parts of your will automatically).

An up-to-date will ensures that no portion of your estate is left in limbo. It’s also wise to include contingent beneficiaries – e.g. “I leave my estate to my sister, but if she predeceases me, then to my niece.” This kind of backup plan can prevent an unintended intestacy.

Communicate Your Wishes: Talk to your family or trusted friends about your plans. It might feel like a morbid topic, but letting people know you have a will and where it’s kept is important. If no one even knows a will exists, they might assume you died intestate and not look for it, leading to unnecessary legal hurdles. Make sure your executor (the person you appoint to administer your will) has a copy or knows how to access it.

If you have no close family, consider informing the main beneficiaries you’ve named (be it a friend or a charity) so they’re aware. Open communication can also prevent disputes and ensure that when the time comes, someone responsible is ready to step in and carry out your wishes.

Organize Your Estate Information: One reason money goes unclaimed is simply that people can’t find it. Keep a list of your assets – bank accounts, insurance policies, superannuation accounts, property titles, etc. – and update it as needed. You don’t necessarily have to share this list widely, but make sure your executor or a trusted person knows where to find it (for example, “all my important papers are in this filing cabinet” or “here’s a USB drive with my financial info”).

Don’t forget digital assets and online accounts. If you’ve got shares, or perhaps some money in an old bank account, include those details. When everything is organized, it’s far less likely something will slip through the cracks and end up on the unclaimed money register later.

Consider All Your Potential Beneficiaries: If you have a small family or none at all, think about who you would like to benefit from your estate. It could be extended relatives you do know (even if the law wouldn’t reach them automatically). It could be a family friend, or someone who cared for you, or a charitable cause close to your heart.

You have the power to name them in your will. By doing so, you ensure your money goes to a meaningful place rather than becoming “government revenue.” Remember, intestacy law wouldn’t give a cent to a friend or a charity – but your will can. As estate planners often say, a will is your voice after death. Use that voice to direct your legacy where you truly want it to go.

Seek Professional Advice if Needed: If your situation is at all complex – say, you’re unsure how to provide for a relative with special needs, or you’re unmarried but have a long-term partner, or you want to set up a trust – consider getting advice from a solicitor or estate planner.

Professionals can help ensure your documents are legally sound and that no part of your estate gets overlooked. They can also advise on things like appointing substitute executors, handling superannuation death nominations, and other finer points. Investing a little in good advice now can save your family a lot of trouble later, and it further guarantees that nothing of yours goes unclaimed or misdirected.

Finally, one more consideration: if you think you might be entitled to someone else’s unclaimed estate (perhaps a relative who passed away), you can be proactive. Each state maintains resources to search for unclaimed estates or money. For example, NSW has an online Unclaimed Money Register, and other states have similar databases.

A quick search might reveal if you or your late relatives have money waiting. It’s worth a try – you might uncover a lost bank account or an inheritance you didn’t know about.

A Final Thought

No one likes to imagine their hard-earned assets going to waste or defaulting to the government by accident. Writing a will and planning your estate may not be the most exciting tasks, but they are acts of care – for your family, for your friends, and for your own peace of mind.As we’ve seen, the laws are there to catch you if you don’t plan (up to a point), but they’re a blunt instrument and can yield some unfortunate outcomes. The power is in your hands to fine-tune what happens when you’re not around.

So, take a moment to reflect: What steps will you take now to make sure your legacy ends up where you want it, and not among the unclaimed millions?