It’s 4 years since the first COVID case in Australia. Here’s how our pandemic experiences have changed over time

- Replies 7

Sebastian Reategui/Shutterstock

It might be hard to believe, but four years have now passed since the first COVID case was confirmed in Australia on January 25 2020. Five days later, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a “public health emergency of international concern”, as the novel coronavirus (later named SARS-CoV-2) began to spread worldwide.

On March 11 the WHO would declare COVID a pandemic, while around the same time Australian federal and state governments hastily introduced measures to “stop the spread” of the virus. These included shutting Australia’s international borders, closing non-essential businesses, schools and universities, and limiting people’s movements outside their homes.

I began my project, Australians’ Experiences of COVID-19, in May 2020. This research has continued each year to date, allowing me to track how Australians’ attitudes around COVID have changed over the course of the pandemic.

Evolving pandemic experiences

We recruited participants from across Australia, including people living in regional cities and towns. Participants range in age from early adulthood to people in their 80s.

The first three stages of the project each involved 40 interviews with separate groups of participants (so 120 people in total). These interviews were done in May to July 2020 (stage 1), September to October 2021 (stage 2), and September 2022 (stage 3). Stage 4 was an online survey with 1,000 respondents, conducted in September 2023.

Limitations of this project include the small sample sizes for the first three stages (as is common with qualitative interview-based research). This means the findings from those phases are not generalisable, but they do provide rich insights into the experiences of the interviewees. The quantitative stage 4 survey, however, is representative of the Australian population.

The findings show that as the conditions of the pandemic and government management have changed across these years, so have Australians’ experiences.

Regular briefings from state premiers were important for participants. LUIS ASCUI/AAP

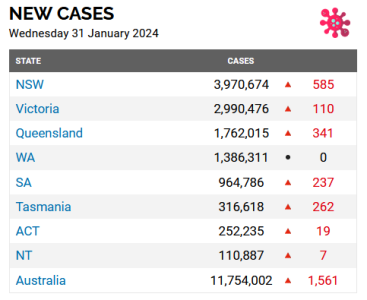

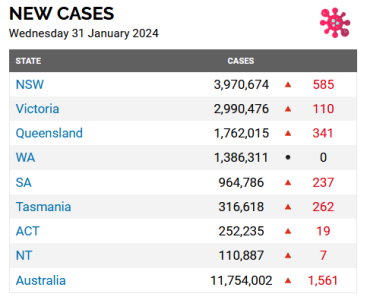

Australians continued to rely heavily on news reports and government announcements in the first two years of the pandemic. Regular briefings from premiers and chief health officers in particular were highly important for how they learned what was happening, as were updates in the media on case numbers, hospitalisations, deaths and progress towards vaccination targets.

Trust has eroded

Australians appear to have lost a lot of trust in COVID information sources such as news media reports, health agencies and government leaders. Early strong support of federal, state and territory governments’ pandemic management in 2020 and 2021 has given way to much lower support more recently.

My 2023 survey (this is published as a report, not peer-reviewed) found doctors were considered the most trustworthy sources of COVID information, but even they were trusted by only 60% of respondents.

After doctors, participants trusted other experts in the field (53%), Australian government health agencies (52%), global health agencies (49%), scientists (45%) and community health organisations (35%). Australian government leaders were towards the lower end of the spectrum (31%).

In 2021, Australians responded positively to the vaccine targets and “road maps” set by governments. These clear guidelines, and especially the promise that the initial doses would remove the need for lockdowns and border closures, were strong incentives to get vaccinated in 2021.

Unfortunately, the prospect that vaccines would control COVID was shown to be largely unfounded. While COVID vaccines were and continue to be very effective at protecting against severe disease and death, they’re less effective at stopping people becoming infected.

Once very high numbers of eligible Australians became vaccinated against the delta variant, omicron reached Australia, resulting in Australia’s first big wave of infection. This led to disillusionment about vaccines’ value for many participants.

In the 2023 survey, respondents reported a high uptake of the first three COVID shots. But when asked whether they planned to get another vaccine in the next 12 months, almost two-thirds said they did not, or they were unsure.

Enter complacency

Complacency now seems to have set in for many Australians. This can be linked to the progressive withdrawal of strong public health measures such as quarantine, mandatory isolation when infected, and testing and tracing regimens.

Meanwhile, the media, government leaders and health agencies have played less of an active public role in conveying COVID information. This has led to uncertainty about the extent to which COVID is still a risk and lack of incentive to take protective actions such as mask wearing.

In 2023, after mandates had ended, only 9% of respondents said they always wore a mask in indoor public places. Only a narrow majority of respondents even supported compulsory masking for workers in health-care facilities.

People have become more lax with mask wearing since mandates ended. Ground Picture/Shutterstock

COVID is still a risk

Whether or not people feel at continuing risk from COVID, the pandemic is still significantly affecting Australians. The 2023 survey found more than two-thirds of respondents (68%) reported having had at least one COVID infection to their knowledge, including 13% who had experienced three or more. Of those who’d had COVID, 40% said they experienced ongoing symptoms, or long COVID.

If the pandemic loses visibility in public forums, people have no way of knowing the risk of infection continues, and are therefore unlikely to take steps to protect themselves and others.

Updated case, hospitalisation, death and vaccination numbers should be communicated regularly, as used to be the case. To combat confusion, complacency and misinformation, all health advice should be based on the latest robust science.

Australians are operating in a vacuum of information from trusted sources. They need much better and more frequent public health campaigns and risk communication from their leaders.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by , Deborah Lupton, SHARP Professor, Vitalities Lab, Centre for Social Research in Health and Social Policy Centre, and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated Decision-Making and Society, UNSW Sydney