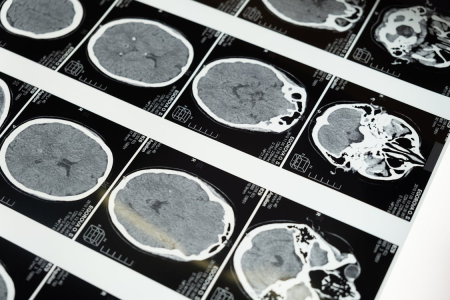

How long can you really live after a dementia diagnosis? The shocking truth revealed

By

Maan

- Replies 0

The reality of living with dementia is complex, and new research has uncovered some surprising insights about how long people can expect to live after a diagnosis.

What once seemed like a straightforward understanding of life expectancy has now been challenged, shedding light on various factors that influence survival rates.

The findings, though unsettling, provide a clearer picture of what lies ahead for those affected by dementia.

A new study revealed the expected life span for individuals diagnosed with dementia, finding that age plays a major role in survival rates.

The study, which reviewed 235 studies involving more than 5.5 million participants, found that survival time following a diagnosis of dementia varied from two to nine years on average.

It examined research from 1984 to 2024 that focused on survival rates and nursing home admissions for dementia patients.

Researchers discovered that men diagnosed at 65 could expect to live for 5.7 years, while those diagnosed at 85 would likely survive for only 2.2 years.

Women diagnosed at 65 had a higher survival expectancy, with an average of 8.9 years, compared to 4.5 years for those diagnosed at 85.

However, women had shorter life expectancy on average because they tended to be diagnosed later than men.

Alzheimer’s disease patients were found to live 1.4 years longer than those diagnosed with other forms of dementia.

Geographically, people in Asia lived 1.4 years longer on average than those diagnosed in Europe or the US.

The average time before dementia patients moved into a nursing home was 3.3 years after diagnosis.

In the first year after diagnosis, 13 per cent of patients moved to a nursing home, with 57 per cent making the move by the fifth year.

The research concluded that more than one-third of a person’s remaining life expectancy would be spent in a nursing home.

‘About one-third of remaining life expectancy was lived in nursing homes, with more than half of people moving to a nursing home within five years after a dementia diagnosis,’ the study authors wrote.

Dr Alex Osborne, policy manager at Alzheimer’s Society, commented on the findings: ‘While this research about life expectancy when living with dementia may be upsetting to read, it’s also a reminder of the vital importance of dementia diagnosis.’

He added: ‘Getting a diagnosis has a wide range of benefits, unlocking access to vital care, support and treatment and helping people to live well for longer.’

‘But right now, a third of people living with dementia in England don’t have a diagnosis at all. This needs to change.’

The Alzheimer’s Society also called on the government to set ambitious targets for diagnosis rates, increase investment in diagnostic tools, and improve access to care across regions.

Health and Social Care Secretary Wes Streeting faced criticism for the lack of a firm deadline for his plans to establish a National Care Service.

An independent commission was set to begin exploring social care reforms, but its work may not be completed until 2028.

Streeting defended the long timeline, saying: ‘Consensus with other political parties is needed because politics has torpedoed good ideas in the past.’

Sir Andrew Dilnot, an economist behind the care costs cap proposal, criticised the length of the commission’s timeline, calling it ‘blindingly… bleedin’ obvious’ that urgent reform to adult social care is necessary.

He argued that three years was an inappropriate period for producing a report on care reform, which should be addressed much sooner.

How do you think these insights will impact the way we support those living with dementia and their families? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

What once seemed like a straightforward understanding of life expectancy has now been challenged, shedding light on various factors that influence survival rates.

The findings, though unsettling, provide a clearer picture of what lies ahead for those affected by dementia.

A new study revealed the expected life span for individuals diagnosed with dementia, finding that age plays a major role in survival rates.

The study, which reviewed 235 studies involving more than 5.5 million participants, found that survival time following a diagnosis of dementia varied from two to nine years on average.

It examined research from 1984 to 2024 that focused on survival rates and nursing home admissions for dementia patients.

Researchers discovered that men diagnosed at 65 could expect to live for 5.7 years, while those diagnosed at 85 would likely survive for only 2.2 years.

Women diagnosed at 65 had a higher survival expectancy, with an average of 8.9 years, compared to 4.5 years for those diagnosed at 85.

However, women had shorter life expectancy on average because they tended to be diagnosed later than men.

Alzheimer’s disease patients were found to live 1.4 years longer than those diagnosed with other forms of dementia.

Geographically, people in Asia lived 1.4 years longer on average than those diagnosed in Europe or the US.

The average time before dementia patients moved into a nursing home was 3.3 years after diagnosis.

In the first year after diagnosis, 13 per cent of patients moved to a nursing home, with 57 per cent making the move by the fifth year.

The research concluded that more than one-third of a person’s remaining life expectancy would be spent in a nursing home.

‘About one-third of remaining life expectancy was lived in nursing homes, with more than half of people moving to a nursing home within five years after a dementia diagnosis,’ the study authors wrote.

Dr Alex Osborne, policy manager at Alzheimer’s Society, commented on the findings: ‘While this research about life expectancy when living with dementia may be upsetting to read, it’s also a reminder of the vital importance of dementia diagnosis.’

He added: ‘Getting a diagnosis has a wide range of benefits, unlocking access to vital care, support and treatment and helping people to live well for longer.’

‘But right now, a third of people living with dementia in England don’t have a diagnosis at all. This needs to change.’

The Alzheimer’s Society also called on the government to set ambitious targets for diagnosis rates, increase investment in diagnostic tools, and improve access to care across regions.

Health and Social Care Secretary Wes Streeting faced criticism for the lack of a firm deadline for his plans to establish a National Care Service.

An independent commission was set to begin exploring social care reforms, but its work may not be completed until 2028.

Streeting defended the long timeline, saying: ‘Consensus with other political parties is needed because politics has torpedoed good ideas in the past.’

Sir Andrew Dilnot, an economist behind the care costs cap proposal, criticised the length of the commission’s timeline, calling it ‘blindingly… bleedin’ obvious’ that urgent reform to adult social care is necessary.

He argued that three years was an inappropriate period for producing a report on care reform, which should be addressed much sooner.

Key Takeaways

- A new study explored the life expectancy of people diagnosed with dementia, revealing that survival rates vary significantly based on factors like age and gender.

- Men diagnosed at 65 can expect to live for 5.7 years, while women diagnosed at 65 may survive up to 8.9 years. However, women tend to be diagnosed later, leading to shorter survival overall.

- Alzheimer’s disease patients generally live longer than those with other forms of dementia, and those in Asia have a slightly longer life expectancy than those in Europe or the US.

- On average, dementia patients move to a nursing home 3.3 years after diagnosis, with more than half making the transition within five years.

How do you think these insights will impact the way we support those living with dementia and their families? Share your thoughts in the comments below.