Friday essay: at 42, my mother discovered her half-sister. Would her childhood have been bearable if they grew up together?

- Replies 0

When I was 22, still living in America, I received a phone call from my mother with that classic opener: “You’ll never believe this.” She told me a woman from an adoption agency had rung, asking if she’d like to be put in touch with her half-sister, born and adopted by another family in 1959. This was the first she’d heard of a half-sister.

The so-called half-sister, Laurie, had begun the search for her biological family because her teenage daughter was having some ongoing health problems and a proper genealogic medical history could be helpful to her prognosis.

Her birth mother, Laurie had discovered, was dead. Her name was Shirley Girard. Her next of kin: my mother. Also daughter of Shirley Girard.

My mother, who was born in 1950, and living with her mother in 1959, was immediately distrustful of a half-sister.

“You’d think a nine-year-old child would be aware of her mother’s pregnancy,” she told the woman from the agency, “but sure, you can give her my number.”

All that night, my mother thought about this half-sister and about the type of mother Shirley was. Eventually, it came to her: those damned varicose veins.

A woman in the flat down the hall had come with a tray of lasagna to get my mother through five dinners. But otherwise, my young mother, only in the third grade, was in charge of herself.

Of course she imagined her mother dying on the operating table. And of course she became so frightened she eventually walked five miles in the rain to the city hospital. Once there, she saw her mother, who – newly emptied of varicose veins and (we now know) a baby girl – told her daughter to go on, walk back home. By then, it was night-time. My mother did as she was told.

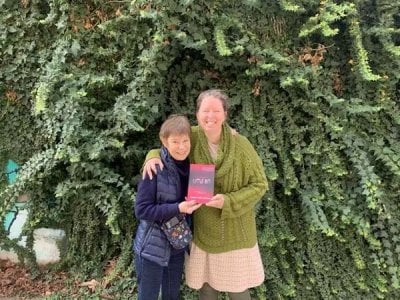

“I blocked the entire pregnancy out,” she told me, when I was 22. “Maybe post-traumatic stress?” She didn’t know: she’s never seen a therapist. But when she met her half-sister at the airport for the very first time – my mother aged 46 and my new aunty aged 37 – she recognised her straight away.

“She looks just like my mother,” my own mother said, “and you – she looks just like you.”

DNA does not lie.

My mother and her half-sister have a happy ending: 28 years since meeting in 1997, they’re the closest of friends. But what if they’d been given the chance to grow up together – and be the closest of sisters?

I think about Vicki Laveau-Harvie’s dysfunctional family memoir, The Erratics, winner of the 2019 Stella Prize. It’s about two sisters who return to their childhood home in Alberta, Canada, after their mother breaks a hip bone and must be hospitalised. The sisters’ plan is to ensure their hectic, narcissistic mother never be allowed back home. And rightfully so, as their mother had been starving their feeble father, making him unwell, for years.

Laveau-Harvie recalls finding, with her sister, shoebox on top of shoebox of old cheque receipts, belonging to their mother, which suggested likely bankruptcy.

“We’ll buy a shredder,” her sister says of the receipts. Vicki nods, thinking maybe a calculator too. She writes:

I think of the revolving doors of the many homes my mother lived in, because her mother couldn’t keep a job and pay the rent. Or because there had been too many disturbance calls from the neighbours – all those men coming and going. The one constant thing about those homes is that they were hugless.

I can’t help but think how the squeeze of her half-sister’s hand in hers might have made living in those ramshackle homes more bearable for my mother.

In 1954, when my mother’s parents divorced, her father took the boy – my Uncle Terry, aged nine – and her mother took the girl – my mother, aged four. The siblings could count on a single hand the number of times they saw each other in their childhoods. The few reunions they did have were awkward and marked by avoidance. Their shared DNA translated to absolutely nothing of importance.

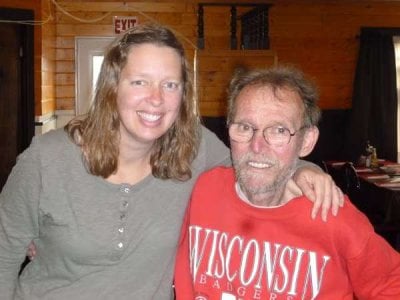

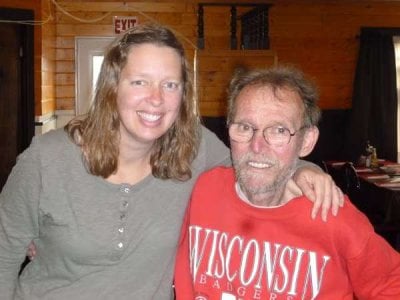

I met with my uncle during the writing of Little Bit – my autofictional novel of my mother’s desperate upbringing, told by three generations of women: my mother, her own mother and myself.

One of the relationships I tried to capture was between my mother and the sibling she knew about. I wrote about a rare visit she paid (with my grandmother) to her father and brother, drawing on the memories she shared with me.

She remembers her father picking her up and spinning her in circles, a “mouldy bread stink” coming from his skin. She thought he would drop her, or maybe spin her so fast that her dress would fly up. She hated his spinning, hated his stubble scratching her face. But when he redirected his attention, she wished he would do it again anyway.

When they reached the cabin where he lived with her brother, my mother felt herself recede into the background. In my mother’s memory, Terry took his time coming out of his room, while her father fossicked for clean glasses and bottles of beer. When Terry finally appeared, he hugged his mother obligingly, but ignored his sister, only hugging her – in great haste – when he was told to. This reluctant, fleeting attention epitomised their relationship, or lack of it.

Though I faithfully reimagined my mother and uncle’s estrangement within the pages of Little Bit, I can’t help envisaging a different scenario entirely. One where they’d been given the opportunity to grow up together. Where they could help one another get through the toughest days of their parent’s divorce and subsequent poverty and addiction, by simply hearing the words, “I know”.

The fierce attachment deficient parenting can foster in siblings, united by the same lack, is reflected in Ann Patchett’s 2019 novel The Dutch House. It’s about two siblings, Danny and Maeve, who are ousted from their eccentric family home by their stepmother after their father dies.

As Danny is still a minor, Maeve is forced to be his guardian. The only thing left to them by their father is an educational trust fund. So, Maeve concocts a plan for Danny’s education to completely drain their stepmother of any financial comfort she might otherwise have enjoyed.

As if losing their father, then their home, isn’t tragic enough, their birth mother had left Danny and Maeve when they were young. She moved to India to help children in need, rather than raising her own children in need.

At one point in the book, when the two incredibly close siblings are both adults, Danny’s girlfriend, Celeste, thinks Maeve told him to break up with her. Celeste says:

Since Danny hasn’t got the option, like others might, of discussing his life decisions with a parent, he tells Celeste: “I’ve got Maeve, okay?”

My mother didn’t have my uncle Terry. Basically they grew into two adults who are, for the most part, strangers. Sometimes they call each other for Christmas, but it is, my mother has told me, a chore. She never knows what to say.

If my mother had the chance to share the burden of Shirley Girard with her brother, or the half-sister we now know exists, I think she would’ve lived a happier life. And I would’ve written a happier book.

According to Bank and Khan, in most cases, the ideal outcome for siblings after the divorce of their parents, or in cases of multiple sibling adoption or fostering, is that they are raised together. This is backed up by a number of family social workers and child psychologists.

In her classic text, A Child’s Journey Through Placement, paediatrician and psychotherapist Vera Fahlber asks a series of questions to assess whether or not siblings should be separated. Would one child not get their needs met? Or would someone’s safety be threatened? But in the absence of special circumstances like these, keeping them together is usually the goal.

In the 1950s, when mothers were expected to stay at home to raise their children rather than join the workforce and earn an income, my grandmother’s decision to hand her son over to his father and to give her unplanned baby up for adoption was twofold.

She knew she wouldn’t be able to financially look after herself and two children – and, as she suffered from undiagnosed PTSD, she wouldn’t be able to emotionally look after herself and two children.

Did she make the right decisions? In giving up her second daughter for adoption, I’d say yes. Absolutely. One hundred percent. My grandmother was so far gone with alcohol and drugs, and her depression was so deep, her little baby’s life would certainly have been in danger.

But what about giving up her son? This one is tricky. My mother and I believe addiction truly took hold of my grandmother after she let her nine-year-old son live solely with his father. This suggests that if my uncle had been brought up with my mother and grandmother, there might not have been such chaos and turmoil in the house.

And what, then, about me? As a member of the next generation, once removed from that household, I feel like a minor consideration in the equation compared to my mother and her own mother, who lived in it. But I am still affected by what happened.

I met with my new aunty while I was writing Little Bit, too. Her name is Laurie and I love her. Not only could I see how my mother would’ve welcomed her straight away – she’s tiny, like my mother, and seems to laugh easily and heartily, also like my mother – but I feel like our DNA meant something.

I don’t know how I can treat the facts of DNA so differently from one relative to another.

In a Four Corners episode last year, two South Korean siblings, both given up for adoption at birth, described finding one another through an at-home DNA test. Will, the younger of the two by exactly one year, lives in Australia, halfway around the world from his sister Riley in America. When they met for the first time at the Sydney Airport, it played out like my mother meeting her sister Laurie.

“I like to think I’m a fairly laid-back person, and she comes into the terminal and I saw her and it hit me and I started bawling,” says Will. “It was weird looking at someone and thinking you’re the girl version of me.”

Riley said: “You learn when you’re adopted that blood doesn’t necessarily make you family and that it’s what you make along the way … finding Will, I think, yeah blood does that too.”

My aunt Laurie had to go through the adoption agency to find my mother in 1996. It was a time-consuming exercise, involving a lot of research and subsequent paperwork. Little did she know, in that same year, the first at-home DNA tests were connecting adoptees and their birth families – without all that rigmarole. It’s estimated more than 100 million people have since spat into small tubes and sent them off in the mail to discover their ancestry.

Outcomes like Will’s and Riley’s aren’t the norm, but they’re not necessarily unusual. Also not unusual are the stories of disconnected families that do not want to be connected. They’re just not aired as feel-good television.

I met another aunty while writing Little Bit, my mother’s half-sister on their father’s side. She has a brother and a sister, too: so there are more siblings my mother was never able to connect with. More relatives I hadn’t known existed.

My mother will tell you that’s all of them, then shake her head as if she’s shaking off the past and say, “But you never know.”

Her father, my mother will tell you with a mixture of humour and disgust, sired half of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where he moved to after his divorce from my grandmother and lived until he died. But if I could find all of those children and confirm we share the same DNA, would it make them family?

DNA does not lie, but neither does it mean everything. Call me a cynic, but I’m starting to think family is a construct.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The so-called half-sister, Laurie, had begun the search for her biological family because her teenage daughter was having some ongoing health problems and a proper genealogic medical history could be helpful to her prognosis.

Her birth mother, Laurie had discovered, was dead. Her name was Shirley Girard. Her next of kin: my mother. Also daughter of Shirley Girard.

My mother, who was born in 1950, and living with her mother in 1959, was immediately distrustful of a half-sister.

“You’d think a nine-year-old child would be aware of her mother’s pregnancy,” she told the woman from the agency, “but sure, you can give her my number.”

All that night, my mother thought about this half-sister and about the type of mother Shirley was. Eventually, it came to her: those damned varicose veins.

DNA does not lie

My mother did not remember her mother’s pregnancy. But she did remember her mother leaving her alone for five days straight, while doctors apparently removed varicose veins from her legs and nurses helped her recover.A woman in the flat down the hall had come with a tray of lasagna to get my mother through five dinners. But otherwise, my young mother, only in the third grade, was in charge of herself.

Of course she imagined her mother dying on the operating table. And of course she became so frightened she eventually walked five miles in the rain to the city hospital. Once there, she saw her mother, who – newly emptied of varicose veins and (we now know) a baby girl – told her daughter to go on, walk back home. By then, it was night-time. My mother did as she was told.

“I blocked the entire pregnancy out,” she told me, when I was 22. “Maybe post-traumatic stress?” She didn’t know: she’s never seen a therapist. But when she met her half-sister at the airport for the very first time – my mother aged 46 and my new aunty aged 37 – she recognised her straight away.

“She looks just like my mother,” my own mother said, “and you – she looks just like you.”

DNA does not lie.

Can deficient parenting deepen sibling bonds?

Sibling relationships in damaged families tend to be more supportive and warm, according to compensation hypothesis. This theory suggests that during a domestic crisis, or periods of serious instability, the sibling connection will strengthen, compensating for the inevitable change in the parent-child bond. Clinical psychologists Stephen Bank and Michael Kahn similarly argue, in their book The Sibling Bond, that deficient parenting is a catalyst for deep sibling attachment.My mother and her half-sister have a happy ending: 28 years since meeting in 1997, they’re the closest of friends. But what if they’d been given the chance to grow up together – and be the closest of sisters?

I think about Vicki Laveau-Harvie’s dysfunctional family memoir, The Erratics, winner of the 2019 Stella Prize. It’s about two sisters who return to their childhood home in Alberta, Canada, after their mother breaks a hip bone and must be hospitalised. The sisters’ plan is to ensure their hectic, narcissistic mother never be allowed back home. And rightfully so, as their mother had been starving their feeble father, making him unwell, for years.

Laveau-Harvie recalls finding, with her sister, shoebox on top of shoebox of old cheque receipts, belonging to their mother, which suggested likely bankruptcy.

“We’ll buy a shredder,” her sister says of the receipts. Vicki nods, thinking maybe a calculator too. She writes:

Put simply: there are no words for what the situation demands.We don’t look at each other, but she squeezes my hand and we stand together like that, looking out the window at the smooth blue surface of the snow in the fading late-afternoon light.

I think of the revolving doors of the many homes my mother lived in, because her mother couldn’t keep a job and pay the rent. Or because there had been too many disturbance calls from the neighbours – all those men coming and going. The one constant thing about those homes is that they were hugless.

I can’t help but think how the squeeze of her half-sister’s hand in hers might have made living in those ramshackle homes more bearable for my mother.

A missing brother, too

I didn’t know much about my mother’s upbringing when I was growing up, but I did know that she and her brother didn’t grow up together, which seemed both senseless and tragic to me.In 1954, when my mother’s parents divorced, her father took the boy – my Uncle Terry, aged nine – and her mother took the girl – my mother, aged four. The siblings could count on a single hand the number of times they saw each other in their childhoods. The few reunions they did have were awkward and marked by avoidance. Their shared DNA translated to absolutely nothing of importance.

I met with my uncle during the writing of Little Bit – my autofictional novel of my mother’s desperate upbringing, told by three generations of women: my mother, her own mother and myself.

Heather Taylor Johnson and her Uncle Terry, who grew up mostly apart from her mother. Heather Taylor Johnson

One of the relationships I tried to capture was between my mother and the sibling she knew about. I wrote about a rare visit she paid (with my grandmother) to her father and brother, drawing on the memories she shared with me.

She remembers her father picking her up and spinning her in circles, a “mouldy bread stink” coming from his skin. She thought he would drop her, or maybe spin her so fast that her dress would fly up. She hated his spinning, hated his stubble scratching her face. But when he redirected his attention, she wished he would do it again anyway.

When they reached the cabin where he lived with her brother, my mother felt herself recede into the background. In my mother’s memory, Terry took his time coming out of his room, while her father fossicked for clean glasses and bottles of beer. When Terry finally appeared, he hugged his mother obligingly, but ignored his sister, only hugging her – in great haste – when he was told to. This reluctant, fleeting attention epitomised their relationship, or lack of it.

Though I faithfully reimagined my mother and uncle’s estrangement within the pages of Little Bit, I can’t help envisaging a different scenario entirely. One where they’d been given the opportunity to grow up together. Where they could help one another get through the toughest days of their parent’s divorce and subsequent poverty and addiction, by simply hearing the words, “I know”.

The fierce attachment deficient parenting can foster in siblings, united by the same lack, is reflected in Ann Patchett’s 2019 novel The Dutch House. It’s about two siblings, Danny and Maeve, who are ousted from their eccentric family home by their stepmother after their father dies.

As Danny is still a minor, Maeve is forced to be his guardian. The only thing left to them by their father is an educational trust fund. So, Maeve concocts a plan for Danny’s education to completely drain their stepmother of any financial comfort she might otherwise have enjoyed.

As if losing their father, then their home, isn’t tragic enough, their birth mother had left Danny and Maeve when they were young. She moved to India to help children in need, rather than raising her own children in need.

At one point in the book, when the two incredibly close siblings are both adults, Danny’s girlfriend, Celeste, thinks Maeve told him to break up with her. Celeste says:

I considered my relationship with my brother when reading that passage. No, he doesn’t run his life decisions by me – but we spent our childhood in an intact and loving family. Danny and Maeve did not. Products of deficient parenting, the siblings are all each other have by way of family.Who talks to their sister about these things anyway? Do you think when my brother was trying to decide whether or not to go to dental school he came out to the Bronx so we could hash it out together? People don’t do that. It isn’t natural.

Since Danny hasn’t got the option, like others might, of discussing his life decisions with a parent, he tells Celeste: “I’ve got Maeve, okay?”

My mother didn’t have my uncle Terry. Basically they grew into two adults who are, for the most part, strangers. Sometimes they call each other for Christmas, but it is, my mother has told me, a chore. She never knows what to say.

Would I have written a happier book?

My mother dealt with extreme neglect and constant chaos on her own. Too afraid of losing friends if they knew how she lived, she kept so many secrets to herself, it’s a wonder she didn’t buckle daily under their weight.If my mother had the chance to share the burden of Shirley Girard with her brother, or the half-sister we now know exists, I think she would’ve lived a happier life. And I would’ve written a happier book.

According to Bank and Khan, in most cases, the ideal outcome for siblings after the divorce of their parents, or in cases of multiple sibling adoption or fostering, is that they are raised together. This is backed up by a number of family social workers and child psychologists.

In her classic text, A Child’s Journey Through Placement, paediatrician and psychotherapist Vera Fahlber asks a series of questions to assess whether or not siblings should be separated. Would one child not get their needs met? Or would someone’s safety be threatened? But in the absence of special circumstances like these, keeping them together is usually the goal.

In the 1950s, when mothers were expected to stay at home to raise their children rather than join the workforce and earn an income, my grandmother’s decision to hand her son over to his father and to give her unplanned baby up for adoption was twofold.

She knew she wouldn’t be able to financially look after herself and two children – and, as she suffered from undiagnosed PTSD, she wouldn’t be able to emotionally look after herself and two children.

Did she make the right decisions? In giving up her second daughter for adoption, I’d say yes. Absolutely. One hundred percent. My grandmother was so far gone with alcohol and drugs, and her depression was so deep, her little baby’s life would certainly have been in danger.

But what about giving up her son? This one is tricky. My mother and I believe addiction truly took hold of my grandmother after she let her nine-year-old son live solely with his father. This suggests that if my uncle had been brought up with my mother and grandmother, there might not have been such chaos and turmoil in the house.

And what, then, about me? As a member of the next generation, once removed from that household, I feel like a minor consideration in the equation compared to my mother and her own mother, who lived in it. But I am still affected by what happened.

Family, DNA and belonging

When I met with my uncle, it was clear he didn’t want to talk about his mother or my mother. Like their awkward reunions when they were children, despite our shared DNA, our time spent together was uncomfortable. I didn’t feel like we belonged to each other in any practical way. I didn’t really feel like we were family.I met with my new aunty while I was writing Little Bit, too. Her name is Laurie and I love her. Not only could I see how my mother would’ve welcomed her straight away – she’s tiny, like my mother, and seems to laugh easily and heartily, also like my mother – but I feel like our DNA meant something.

I don’t know how I can treat the facts of DNA so differently from one relative to another.

In a Four Corners episode last year, two South Korean siblings, both given up for adoption at birth, described finding one another through an at-home DNA test. Will, the younger of the two by exactly one year, lives in Australia, halfway around the world from his sister Riley in America. When they met for the first time at the Sydney Airport, it played out like my mother meeting her sister Laurie.

“I like to think I’m a fairly laid-back person, and she comes into the terminal and I saw her and it hit me and I started bawling,” says Will. “It was weird looking at someone and thinking you’re the girl version of me.”

Riley said: “You learn when you’re adopted that blood doesn’t necessarily make you family and that it’s what you make along the way … finding Will, I think, yeah blood does that too.”

My aunt Laurie had to go through the adoption agency to find my mother in 1996. It was a time-consuming exercise, involving a lot of research and subsequent paperwork. Little did she know, in that same year, the first at-home DNA tests were connecting adoptees and their birth families – without all that rigmarole. It’s estimated more than 100 million people have since spat into small tubes and sent them off in the mail to discover their ancestry.

Outcomes like Will’s and Riley’s aren’t the norm, but they’re not necessarily unusual. Also not unusual are the stories of disconnected families that do not want to be connected. They’re just not aired as feel-good television.

I met another aunty while writing Little Bit, my mother’s half-sister on their father’s side. She has a brother and a sister, too: so there are more siblings my mother was never able to connect with. More relatives I hadn’t known existed.

My mother will tell you that’s all of them, then shake her head as if she’s shaking off the past and say, “But you never know.”

Her father, my mother will tell you with a mixture of humour and disgust, sired half of Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where he moved to after his divorce from my grandmother and lived until he died. But if I could find all of those children and confirm we share the same DNA, would it make them family?

DNA does not lie, but neither does it mean everything. Call me a cynic, but I’m starting to think family is a construct.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.