SDC Rewards Member

Upgrade yours now

A

Forced Adoption: Australia’s White Stolen Generation

The author wishes to remain anonymous.

Warning: This content may be upsetting for some readers. Please note that this is quite personal so please comment with caution and compassion.

Warning: This content may be upsetting for some readers. Please note that this is quite personal so please comment with caution and compassion.

Mrs X is a 51-year-old wife, mother of two and a retired member of the Royal Australian Air Force. She also happens to be my mother. A recurring source of pain in her life is her adoption at six months old, before which she lived in a Queensland orphanage. The orphanage, like many, is long gone.

We’re sitting at her kitchen island on a Saturday night. She’s just returned from a Vespa Club outing wearing a scooter-printed shirt. The apartment is quiet despite its location in the heart of the city. She likes being able to walk into the CBD. On her coffee table lies Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and Eckhart Tolle’s A New Earth, the first of which I gifted her for Christmas and remains unread. The latter she refers to as her ‘Bible’ for its spiritual teachings.

Mrs X is one of many children now referred to as Australia’s White Stolen Generation.

‘I don’t want to take it away from the Indigenous. But we are a stolen generation. The Government took the children–they weren’t taken like the Indigenous–it was that socially-, they could not look after a child and if the families did not say I will raise the child or help you raise the child then the child was given up for adoption.’

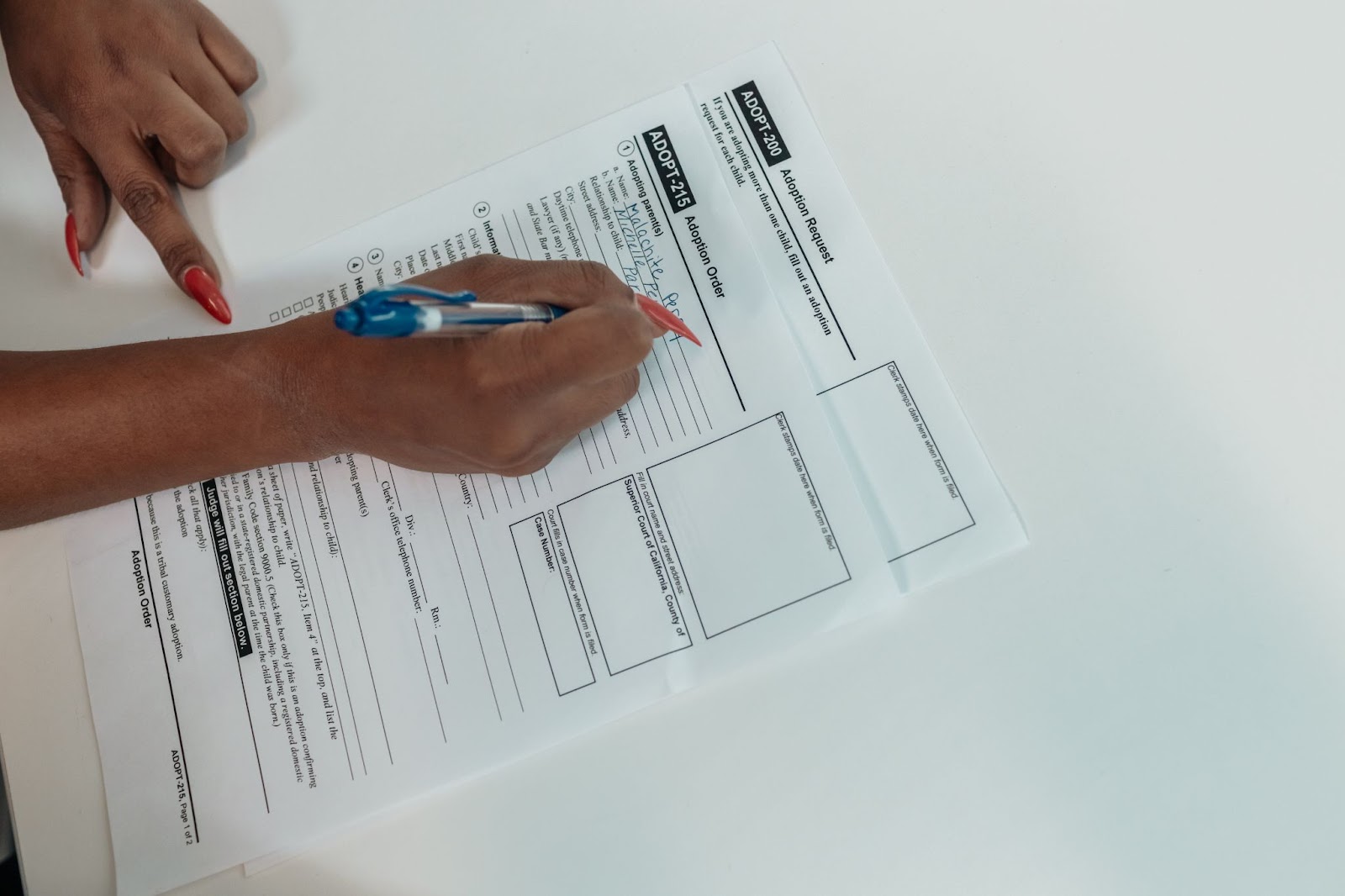

Government practices stole babies from their families. Image Source: Pexels

Government practices stole babies from their families. Image Source: Pexels

Dr Higgin’s research ‘Unfit mothers … unjust practices?’ confirms these adoption practices had ‘lifelong consequences’ for both mother and child with over 35,000 adoptions estimated to have occurred between 1968 and 1980. The Australian Government delivered a formal apology to people affected by past forced adoption or removal policies and practices in 2013.

Then-PM Julliad Gillard acknowledged it was government policies that ‘forced the separation of mothers from their babies, which created a lifelong legacy of pain and suffering’. The apology touched on something that plagues Mrs X to this day: ‘To each of you who were …led to believe your mother had rejected you and who were denied the opportunity to grow up with your family and community of origin and to connect with your culture, we say sorry.’ But 'sorry' cannot take away the ingrained trauma.

Mrs X’s biological mother and father were unwed, the former of which was only sixteen years old. She recalls being told that when her brother was born, a year before her, their biological father stole him from the hospital and was subsequently put into jail. Mrs X was conceived upon his release but he would not find out about the pregnancy until the baby girl was born, in the late 1960s, and placed in an orphanage. Regardless, it went unsaid, no one had tried to steal her to safety.

Visibly emotional, Mrs X explains, ‘just imagine from zero to six months, that child is not loved. There is no love for that child to learn how to, you know, get on with-, it’s... it’s a tough one for anyone to understand.’

She props her elbows onto the bench and clasps her hands together as if to ground herself. Her chin comes to rest on her surprisingly steady hands. While I no longer live at home, my laundry rattles in the background.

Empty beds and empty cradles. Image Source: Pexels.

She recalls being eight years old when she was told of her adoption and remembers exactly where she was at the time. ‘It didn’t really resonate with me and I remember going off after that and playing a game of tennis with somebody … I said “Oh, I’ve just been told I’m adopted”.’ Two other girls in her thirty-two-student school were also adopted.

‘I don’t think we ever spoke about it.’

Her silence has continued up until now; something she blames on fear of further rejection. At 21, a recent Air Force recruit and admitted ‘run-away,’ Mrs X started to look for her biological mother through the adoption ‘search and contact’ company Jigsaw. ‘They got back to me and said, “Do you realise you have a brother?” and I thought “Oh f***, I already have four”.’

Despite having already discussed the adoption generally, when the interview steers toward how it impacted her, Mrs X began to cry.

‘I’ve never really let myself get close to a lot of people... Not many people have got in… maybe that was the survival in the first six months of my life. I knew what I needed to do to survive.’

‘Why do you think that is?’ I prompt.

‘Because I didn’t learn how to love, I didn’t learn what compassion was.’

Despite being placed in a home at six months old, her life did not improve. She explained that the orphanages were closing and families that were previously rejected from adopting due to their financial situation were now handed children, with essentially no questions asked. ‘They literally had to get rid of us out of the orphanages.’

‘Get rid of us’ rings in my ears long after the interview ends.

Mrs X had been adopted by a family undeniably living in poverty. Her adoptive mother had an ectopic pregnancy where she lost who she believed to be her daughter. In turn, she went to the orphanage and brought home Mrs X. In her new home Mrs X was beaten and treated as a maid, something she refers to as ‘Cinderella Syndrome’. While she didn’t wish to delve into this part of her history, she confirmed she was also physically and sexually assaulted throughout her childhood by her adoptive brothers; something she has never received an apology for or any sort of acknowledgement of from her family. The impact on her psyche has been profound:

'If a mother cannot love you… and when you’re adopted, it depends who you’ve gone to…I’m not the only person who is gonna go “I’ve had two mothers that have not loved me.” I’m not the only one. Mum doesn’t even say happy birthday to me, doesn’t ring me… doesn’t acknowledge my birthday because she wasn’t there.'

The dryer chimes, we’d both forgotten it was on. When I return, we discuss other adoptees and whether she had any advice she would like to offer.

‘First of all, I’d try not to burden them with my story.’ This thought has appeared throughout the interview, that her story is not worth sharing, a remnant of the emotional turmoil of her childhood.

‘It’s always there, it’s always in the background…My advice would be to accept what’s happened, acknowledge what’s happened but be grateful for what you have now.’

A horrific stain on Australian history. Image Source: Pexels.

Before I head home, she helps me fold everything. She relaxes as we sit side by side. While Mrs X did not have a positive mother figure, when I think of my childhood and current relationship with her, I know she figured motherhood out.

Did other adoptees from my mother’s generation find their families? It is likely to remain an intimate part of history that will go largely untold.