Family united with 121yo diary dropped off at Adelaide RSL club

By

ABC News

- Replies 0

A 121-year-old diary left on the doorstep of an RSL club in Adelaide has been united with the writer's grandson and his family.

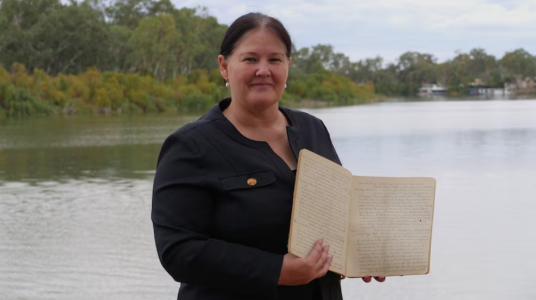

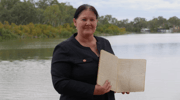

In the South Australian Riverland town of Renmark, Vicki Dunhill received a text from a friend alerting her to rumours a diary was floating around with her last name attached to it.

"When I saw it, I was like, 'Oh my God, that's my husband's grandfather,"' she said.

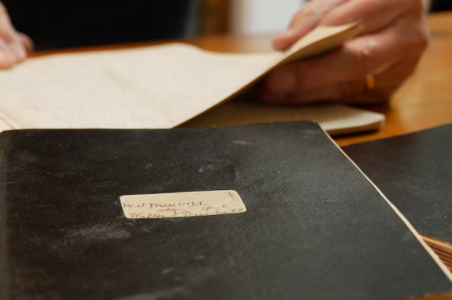

Walter James Dunhill's diary, dated from 1904 to 1916, was found near the front door of the Semaphore RSL club in Adelaide, more than 250 kilometres from Renmark, in January.

"The president told us he had looked through CCTV to find who dropped it off...[but] they couldn't find anything."

"Isn't that just the weirdest thing?"

But as Ms Dunhill and her husband Deane sat down to read his grandfather's diary, the mystery deepened.

Man behind the mystery

Walter James Dunhill was born in the Adelaide suburb of Thebarton in 1878 and lived in Renmark until he died, aged 74, in 1953.

According to the South Australian electoral roll, from 1939 he worked as a compositor at the local newspaper.

"[Walter] died the day after [my husband's] parents got married, so he and his four brothers never met their grandfather," Ms Dunill said.

While some of Walter's diary entries were written during WWI, it is still unknown whether he served in Australia's military efforts during this time.

From what has been deciphered, there are suggestions he was involved in Australia's Merchant Navy.

"There are references and terminology the Semaphore RSL president said would be really difficult to know if you hadn't served, but we can't say for sure," Ms Dunhill said.

Walter's mysterious past is complicated by the variations of his name across historical documents.

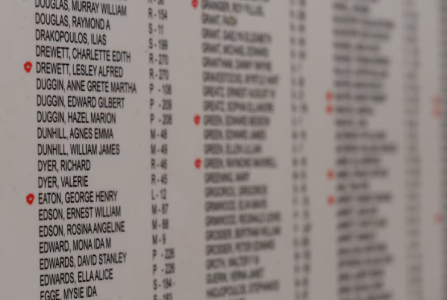

According to the Renmark Cemetery records, he is listed as William James Dunhill on its database.

A window on pre-WW1

Head of the Australian War Memorial research centre Robyn Van Dyk said it was common for people to enlist using an alias or their mother's maiden name during WWI.

"A lot of the time it was because they were under age, or perhaps they were knocked back on health reasons, so this was their second or third shot at joining," she said.

In Walter's case, Ms Van Dyk believes "something has gone wrong" as families "can usually trek their way through records and find their person".

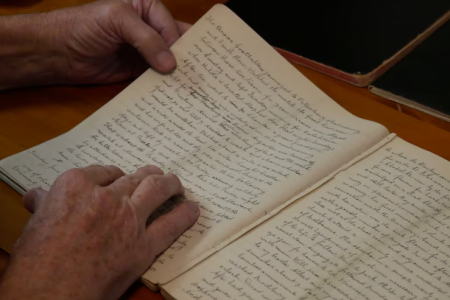

An added layer to Walter's hidden past is the issue of deciphering cursive writing, a skill Ms Van Dyk says is slowly fading away.

"Handwriting today is so different to the First World War … even what we learnt at school and how to write at school now has changed in the last 50 years," she said.

Ms Van Dyk said if the family discovered Walter did not serve, his diaries were still valuable to Canberra's War Memorial to shed more light on pre-WWI times in Australia.

"I think these diaries are more important than people realise," she said.

Discovery brings together relatives

Since Walter's diary was returned to the Dunhill family, relatives from Western Australia and even Costa Rica have come forward with images and additional diaries belonging to him.

They are dated after the diary found at the RSL club.

Ms Dunhill said they were now in regular contact with relatives and hoped to meet in person some day soon.

In the meantime, she said they would continue to try to find out more about their family tree.

"[Deane and I] are going overseas to Scotland, England, and Wales in November and Walter's parents are actually buried at Leeds, so we really hope to find the rest of the Dunhill family."

Written by Amelia Walters, ABC News.

In the South Australian Riverland town of Renmark, Vicki Dunhill received a text from a friend alerting her to rumours a diary was floating around with her last name attached to it.

"When I saw it, I was like, 'Oh my God, that's my husband's grandfather,"' she said.

Walter James Dunhill's diary, dated from 1904 to 1916, was found near the front door of the Semaphore RSL club in Adelaide, more than 250 kilometres from Renmark, in January.

"The president told us he had looked through CCTV to find who dropped it off...[but] they couldn't find anything."

"Isn't that just the weirdest thing?"

But as Ms Dunhill and her husband Deane sat down to read his grandfather's diary, the mystery deepened.

Man behind the mystery

Walter James Dunhill was born in the Adelaide suburb of Thebarton in 1878 and lived in Renmark until he died, aged 74, in 1953.

According to the South Australian electoral roll, from 1939 he worked as a compositor at the local newspaper.

"[Walter] died the day after [my husband's] parents got married, so he and his four brothers never met their grandfather," Ms Dunill said.

While some of Walter's diary entries were written during WWI, it is still unknown whether he served in Australia's military efforts during this time.

From what has been deciphered, there are suggestions he was involved in Australia's Merchant Navy.

"There are references and terminology the Semaphore RSL president said would be really difficult to know if you hadn't served, but we can't say for sure," Ms Dunhill said.

Walter Dunhill (third back left) was said to be a philosophical man who loved literature. (Supplied: Tania Morton)

Deane Dunhill said while he never met his grandfather, he recalled hearing a conversation about him as a young boy.

"Dad was talking with his mother and said [Walter] always wanted to be in the navy, but he couldn't go on a ship without getting seasick," Deane said.

"Dad was talking with his mother and said [Walter] always wanted to be in the navy, but he couldn't go on a ship without getting seasick," Deane said.

To date, there are no records of a Walter James Dunhill serving in any capacity for Australia's military forces in World War I, nor any records in the National Australian Archives.

Walter's mysterious past is complicated by the variations of his name across historical documents.

According to the Renmark Cemetery records, he is listed as William James Dunhill on its database.

A window on pre-WW1

Head of the Australian War Memorial research centre Robyn Van Dyk said it was common for people to enlist using an alias or their mother's maiden name during WWI.

"A lot of the time it was because they were under age, or perhaps they were knocked back on health reasons, so this was their second or third shot at joining," she said.

In Walter's case, Ms Van Dyk believes "something has gone wrong" as families "can usually trek their way through records and find their person".

An added layer to Walter's hidden past is the issue of deciphering cursive writing, a skill Ms Van Dyk says is slowly fading away.

"Handwriting today is so different to the First World War … even what we learnt at school and how to write at school now has changed in the last 50 years," she said.

Ms Van Dyk said if the family discovered Walter did not serve, his diaries were still valuable to Canberra's War Memorial to shed more light on pre-WWI times in Australia.

"I think these diaries are more important than people realise," she said.

Discovery brings together relatives

Since Walter's diary was returned to the Dunhill family, relatives from Western Australia and even Costa Rica have come forward with images and additional diaries belonging to him.

They are dated after the diary found at the RSL club.

Ms Dunhill said they were now in regular contact with relatives and hoped to meet in person some day soon.

In the meantime, she said they would continue to try to find out more about their family tree.

"[Deane and I] are going overseas to Scotland, England, and Wales in November and Walter's parents are actually buried at Leeds, so we really hope to find the rest of the Dunhill family."

Written by Amelia Walters, ABC News.