Discover the Untold Story of the Australian Icon Who Changed Aviation Forever!

By

Danielle F.

- Replies 2

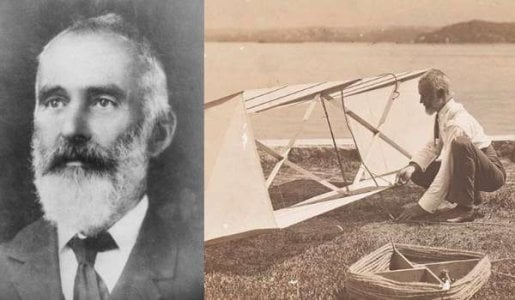

The annals of aviation history are replete with tales of daring, innovation, and the relentless pursuit of the dream to soar above the clouds. Yet, amidst the pantheon of pioneers who propelled humanity into the skies, the name Lawrence Hargrave often flies under the radar. This year, we celebrate the 130th anniversary of a momentous event that unfolded on a remote Australian beach—an event that would forever alter the trajectory of human flight.

On November 12, 1894, Lawrence Hargrave, an English-born Australian inventor, took to the windswept sands of Stanwell Park Beach near Wollongong, and with the aid of his groundbreaking invention—a flying machine composed of four box kites—ascended 16 feet (4.8 meters) into the air. This feat was not just a personal triumph for Hargrave but a monumental proof-of-concept that heavier-than-air flight was not only possible but within the grasp of mankind.

Hargrave's 'cellular' kite design was a marvel of ingenuity, and its influence rippled across the globe, inspiring other aviation pioneers, including the Wright Brothers. These American siblings would go on to achieve the first powered flight with a pilot on board nearly a decade later. However, unlike the Wrights, who shrouded their designs in secrecy and secured patents, Hargrave's approach was one of unbridled generosity. He famously declared his inventions to be 'at the service of any experimenter who wishes to use it.'

Richard Webb, an engineer who painstakingly rebuilt Hargrave's flying machine for the 130th-anniversary celebration, highlighted the profound impact of Hargrave's altruism. The Wright Brothers themselves benefited from Hargrave's largesse, incorporating his ideas into their designs—some of which they patented. Hargrave's decision not to patent his inventions meant that his groundbreaking work was freely available for the world to build upon.

The original flight, powered by gusts of wind reaching 30 kilometres per hour, was a testament to Hargrave's vision and persistence. Although a re-enactment of the historic flight was thwarted by insufficient wind, onlookers were treated to the flight of individual kites, showcasing the principles behind Hargrave's revolutionary design. As Webb succinctly put it, Hargrave's work proved that 'once you developed a motor to drive it, you had the first aeroplane virtually.'

Lawrence Hargrave's journey to that fateful day was marked by curiosity and a relentless drive to understand the mechanics of flight. Born in Greenwich, England, in 1850, Hargrave emigrated to Australia at the age of 15 with his father. His career path meandered through various roles, including that of an engineer on expeditions and an astronomer at the Sydney Observatory. However, it was the untimely death of his father that spurred him to abandon his job and dedicate himself to the pursuit of aeronautical engineering.

Hargrave's contributions to aviation extended beyond his famous box kites. In 1889, after numerous failed attempts, he developed a three-cylinder rotary engine that would become a staple in early powered flight, particularly during World War I. His insights into wing design were equally groundbreaking; in 1892, he discovered that curved wing surfaces offered greater lift than flat ones—a revelation that would become a cornerstone of aircraft design.

The inventor's move to Stanwell Park in 1893 was strategic, chosen for its robust coastal winds that would prove essential for his experiments. Despite setbacks, including an initial failure of his box kite design, Hargrave's perseverance paid off. His correspondence with fellow inventors, such as the Frenchman Octave Chanute, and his willingness to share his findings, ensured that his legacy would endure.

Hargrave's disdain for patents was matched by his commitment to knowledge dissemination. Between 1884 and 1906, he published at least 28 papers in scientific journals and donated his models to museums, ensuring public access to his work.

As we reflect on the 130th anniversary of Lawrence Hargrave's pioneering flight, we not only celebrate his technical achievements but also his spirit of open collaboration and his belief in the collective advancement of human knowledge. His story is a poignant reminder that the quest for innovation is not just about personal glory but about contributing to a greater good that transcends borders and generations.

So, dear members of the Seniors Discount Club, let us take a moment to honour the legacy of Lawrence Hargrave—an Australian icon whose vision lifted humanity towards the heavens and whose generosity ensured that the skies would be open to all who dared to dream of flight. Share with us your thoughts on this remarkable figure and how his spirit of innovation and sharing can inspire us today.

On November 12, 1894, Lawrence Hargrave, an English-born Australian inventor, took to the windswept sands of Stanwell Park Beach near Wollongong, and with the aid of his groundbreaking invention—a flying machine composed of four box kites—ascended 16 feet (4.8 meters) into the air. This feat was not just a personal triumph for Hargrave but a monumental proof-of-concept that heavier-than-air flight was not only possible but within the grasp of mankind.

Hargrave's 'cellular' kite design was a marvel of ingenuity, and its influence rippled across the globe, inspiring other aviation pioneers, including the Wright Brothers. These American siblings would go on to achieve the first powered flight with a pilot on board nearly a decade later. However, unlike the Wrights, who shrouded their designs in secrecy and secured patents, Hargrave's approach was one of unbridled generosity. He famously declared his inventions to be 'at the service of any experimenter who wishes to use it.'

Richard Webb, an engineer who painstakingly rebuilt Hargrave's flying machine for the 130th-anniversary celebration, highlighted the profound impact of Hargrave's altruism. The Wright Brothers themselves benefited from Hargrave's largesse, incorporating his ideas into their designs—some of which they patented. Hargrave's decision not to patent his inventions meant that his groundbreaking work was freely available for the world to build upon.

The original flight, powered by gusts of wind reaching 30 kilometres per hour, was a testament to Hargrave's vision and persistence. Although a re-enactment of the historic flight was thwarted by insufficient wind, onlookers were treated to the flight of individual kites, showcasing the principles behind Hargrave's revolutionary design. As Webb succinctly put it, Hargrave's work proved that 'once you developed a motor to drive it, you had the first aeroplane virtually.'

Lawrence Hargrave's journey to that fateful day was marked by curiosity and a relentless drive to understand the mechanics of flight. Born in Greenwich, England, in 1850, Hargrave emigrated to Australia at the age of 15 with his father. His career path meandered through various roles, including that of an engineer on expeditions and an astronomer at the Sydney Observatory. However, it was the untimely death of his father that spurred him to abandon his job and dedicate himself to the pursuit of aeronautical engineering.

Hargrave's contributions to aviation extended beyond his famous box kites. In 1889, after numerous failed attempts, he developed a three-cylinder rotary engine that would become a staple in early powered flight, particularly during World War I. His insights into wing design were equally groundbreaking; in 1892, he discovered that curved wing surfaces offered greater lift than flat ones—a revelation that would become a cornerstone of aircraft design.

The inventor's move to Stanwell Park in 1893 was strategic, chosen for its robust coastal winds that would prove essential for his experiments. Despite setbacks, including an initial failure of his box kite design, Hargrave's perseverance paid off. His correspondence with fellow inventors, such as the Frenchman Octave Chanute, and his willingness to share his findings, ensured that his legacy would endure.

Hargrave's disdain for patents was matched by his commitment to knowledge dissemination. Between 1884 and 1906, he published at least 28 papers in scientific journals and donated his models to museums, ensuring public access to his work.

As we reflect on the 130th anniversary of Lawrence Hargrave's pioneering flight, we not only celebrate his technical achievements but also his spirit of open collaboration and his belief in the collective advancement of human knowledge. His story is a poignant reminder that the quest for innovation is not just about personal glory but about contributing to a greater good that transcends borders and generations.

Key Takeaways

- Lawrence Hargrave was an Australian aviation pioneer who, on November 12, 1894, achieved a significant breakthrough in the field of flight by being lifted 16 feet into the air with a flying machine made of box kites.

- Unlike the Wright Brothers, Hargrave did not patent his inventions, instead offering them freely for others to use, which influenced future developments in aviation including those made by the Wright Brothers.

- The 130th anniversary of Hargrave's flight saw a re-enactment plan halted due to insufficient wind, but individual kites were flown to demonstrate the principles of Hargrave's innovation.

- Hargrave's contributions extended beyond his kites to the development of the rotary engine and the discovery that curved wing surfaces provided greater lift, both pivotal in the progression of aircraft technology.