Deepfake videos of Norman Swan are tricking people into buying unproven supplements at a risk to their own health

By

ABC News

- Replies 0

It started about 18 months ago. It was shocking then and is even more so now.

Listeners, viewers, friends, colleagues and family started to contact me, all with roughly the same question, then and now:

"Is this ad I've seen with you in it real? And should I buy the product?"

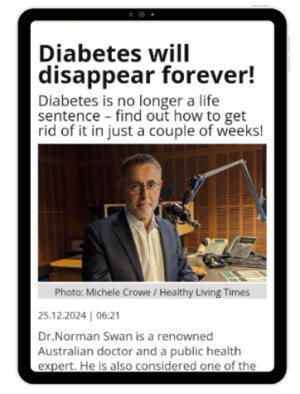

What they had seen was a video or article, via Facebook or Instagram, which featured me flogging supplements or weight loss products purporting to treat heart disease, diabetes or obesity.

I was often denigrating the medical profession and calling the prevailing scientific wisdom "stupid".

When the first ones appeared I asked the ABC to see if they could have them taken down. That didn't work.

Then this year these fake ads started again. They were much more sophisticated and in much larger volumes.

Fake Norman is currently out there spruiking four unproven products that I know of.

One AI-generated video which keeps appearing on Facebook features Rebel Wilson talking about losing weight thanks to a new supplement recommended by "Dr Norman Swan".

Another deepfake follows the same format but with singer Adele. These deepfakes link to an external website for an unproven weight loss product called Keto Flow + ACV.

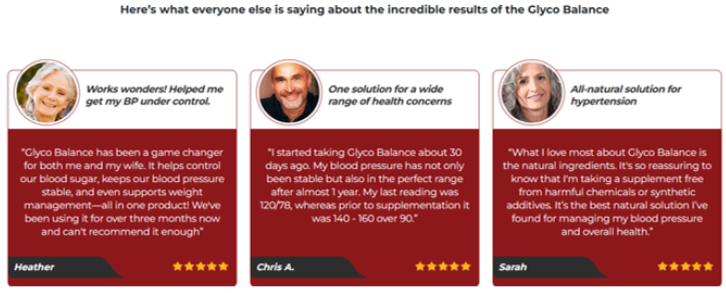

Another pernicious scam involving me is for an unproven product called Glyco Balance.

Both Glyco Balance and Keto Flow + ACV are allegedly made from "all natural" ingredients (although the ingredients list changes depending on what website you visit). They have little or no scientific basis to back up the marketing claims, but the sales pitch is far from benign.

Dangerous health advice

David Bell lives in a retirement village in the northern suburbs of Melbourne.

He is well-educated — his hobby is translating Russian poets of the 19th and early 20th centuries into English — but David's health is poor and he has diabetes.

When an article supposedly penned by me popped up on his laptop it got his attention.

"I thought, 'this is interesting. I wonder what Norman's got to say about diabetes'," he told me.

"It was compelling. And what it was saying was that there is … a chemical called metformin, and it is not beneficial to the body. You should stop taking it."

Metformin is one of the core drugs used to treat type-2 diabetes and is effective in helping to prevent diabetes complications such as blindness and kidney damage.

The article encouraged diabetes patients to stop their metformin and start taking Glyco Balance instead.

The article was so convincing that David ceased his prescribed medication.

"I'm angry with myself for having fallen for it but you're an authority," David told me.

"You're a well-known figure in the health service. Why would I not believe you?"

Late in 2024, another ad for Glyco Balance with similar content appeared on Meta platforms.

This time, instead of me, it was an AI-generated video of leading diabetes researcher and specialist Jonathan Shaw, of the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne.

It was this deepfake that drew in Adelaide resident Janis as she sought to lose weight.

"I researched him … and saw that he was really high up in the heart and diabetes [medical space] in Australia," she told 7.30.

"So I thought, 'Wow this guy's put this product together. It's Australian. I'll give it a go.'"

When Janis's order arrived, the dose on the bottle was 204 milligrams, but the advertised amount was 800mg.

Her bank account also had more than $300 removed instead of just over $200 and eventually Janis discovered that the company had put in place a monthly debit of more than $300 without her being aware of it.

Even with all that, she did try the supplement to see what happened.

"Actually, as far as I'm talking about losing weight … I put on a few kilos while I was taking the first bottle," Janis told 7.30.

Tracking those responsible

7.30 has found three registered businesses linked to Glyco Balance and Keto Flow + ACV: Vellec Group NZ Ltd, Healthy Life Choices NZ Ltd and Apex United Pty Ltd.

They have offices in Christchurch and the Gold Coast, and appear to be connected to a global company based in the US.

They use the same sales and marketing playbook, the same website layout and the same deceptive tactics to lure in consumers.

7.30 has found that some of the people involved in running these companies are related to each other.

Numerous customers all have the same complaints about both products. Namely: people are being overcharged and signed up to a monthly auto-debit without their permission.

7.30 has emailed and phoned the companies involved and contacted their Auckland-based accountant. Apart from one person denying he had anything to do with the business despite being the sole registered director, we have had no other responses.

Since the businesses have been contacted, the main order pages for Glyco Balance have been taken down.

Affiliate websites now redirect customers to order pages for "Glucovate" and "Glyco Forte".

A search through internet archives reveals other name changes the product has undergone in the past, including Blood Balance — the version I was first deepfaked in relation to 18 months ago.

How deepfakes are made

These fakes are remarkably easy to make.

"You need a laptop, internet connection, access to some free or paid software, so it's not a capital-intensive business," said Sanjay Jha from UNSW's School of Computer Science and Engineering.

He and his student Wenbin Wang have developed an artificial intelligence model for teaching purposes. They showed us how the scammer likely created my deepfakes.

The scammer starts with a video of me, taken from a platform like YouTube. They then upload it to a deepfake program that can be purchased for a few dollars.

First, my voice is cloned from a sample which can be as short as a few seconds. The AI model then clones my appearance, scanning the video of me frame by frame, mapping my face from various angles. Then the scammer can type in what words they want me to say.

Meta's 'get-out' card

When Professor Shaw began to receive emails and calls from people wanting to stop their medication or wanting to know where they could get the supplement, he knew there was an issue.

His initial attempts to get Meta to take down the fake ad got nowhere until the Baker Institute's lawyers advised Meta there had been a breach of trademark and intellectual property.

That is when they got a response and had the scam taken down. But new versions kept on appearing.

The ABC has also had trouble getting the attention of Meta.

Rod McGuinness is the ABC's social community lead and coordinates the ABC's presence on social media. He has had over a dozen ABC personalities used by scammers, including Karl Kruszelnicki, Alan Kohler, Michael Rowland and Virginia Trioli.

"We spend a lot of time, or certainly have over the years, reporting these things, saying to Meta, 'can you do something about this?' And very often there's no response," McGuinness told 7.30.

In 2024, Meta made over $US164 billion, most of which was advertising revenue. Scammers exploit Facebook and Instagram's algorithms, targeting vulnerable consumers via paid posts.

Up until now, Meta has largely shirked responsibility. Mr McGuinness says he has been frustrated by its lack of responsibility.

"Facebook have always said they're not publishers — it's the people that use Facebook that are the publishers," he said.

"And I think in this context that's quite a nice get out because they can say, well, we don't control these things. However, they are happy to take the ad revenue."

Nathaniel Gleicher is the director of security policy and global head of counter fraud at Meta. He says the organisation faces a significant challenge.

"We're talking about sophisticated operations working at industrial scale, often backed by criminal organisations that are highly resourced … and are looking to target people wherever they can find them," Mr Gleicher said.

"They're very quick to adjust their tactics to defeat any defences you put in place."

He also maintains that Meta has been highly proactive in its approach to deepfake scams.

"In the fourth quarter of 2024 we removed more than a billion fake accounts and, 99.7 per cent of those, we removed proactively before anyone noticed them," he said.

But a miss rate of 0.3 per cent in more than a billion accounts means there are still a lot of scams slipping through.

"One of the real challenges is that these scams abuse multiple systems," Mr Gleicher said.

"The scammer starts by creating a fake bank account to receive the money — they often need a warehouse to store the actual products that they might be shipping [then] they will move people to a website on the open internet, and then, obviously, they're using an instant payment system.

"To counter this, you really need each of these communities working together."

Aussies lose more than $2 billion

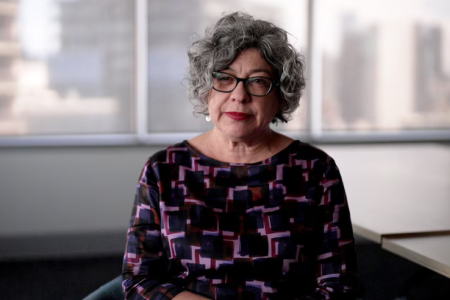

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) runs the National Anti-Scam Centre.

ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe says that controlling these scams is complex and requires cooperation with local and international law enforcement and proactive work by carriers such as Meta.

"We have released a report that demonstrates an over 25 per cent decline in reported financial losses to scams during 2024, but with $2 billion lost, we still have plenty of work to do," she said.

New legislation has given the regulator the power to impose multimillion-dollar fines if platforms fail to remove scam content and these platforms are on notice.

"We anticipate that social media, including Meta, will be one of the early designated sectors," Ms Lowe said.

"That will mean that there will be financial penalties to that sector if they do not fulfil or take reasonable steps to fulfil their obligations under that law."

But that still leaves people like David and Janis to cope by themselves after getting scammed.

"I felt really shattered," Janis told 7.30.

"It was horrible, because I thought this was really real. So it took me back because I had thought I'd just bought this miracle drug."

Professor Shaw thinks the damage goes even deeper than the health and financial risks.

"What happens as a result of this and other similar things is mistrust," he said.

"Maybe all sorts of useful things that I and other people might say about health will not be trusted."

Watch 7.30, Mondays to Thursdays 7:30pm on ABC iview and ABC TV.

Written by Norman Swan, Hannah Meagher, ABC News.

Listeners, viewers, friends, colleagues and family started to contact me, all with roughly the same question, then and now:

"Is this ad I've seen with you in it real? And should I buy the product?"

What they had seen was a video or article, via Facebook or Instagram, which featured me flogging supplements or weight loss products purporting to treat heart disease, diabetes or obesity.

I was often denigrating the medical profession and calling the prevailing scientific wisdom "stupid".

When the first ones appeared I asked the ABC to see if they could have them taken down. That didn't work.

Then this year these fake ads started again. They were much more sophisticated and in much larger volumes.

One AI-generated video which keeps appearing on Facebook features Rebel Wilson talking about losing weight thanks to a new supplement recommended by "Dr Norman Swan".

Another deepfake follows the same format but with singer Adele. These deepfakes link to an external website for an unproven weight loss product called Keto Flow + ACV.

Another pernicious scam involving me is for an unproven product called Glyco Balance.

Both Glyco Balance and Keto Flow + ACV are allegedly made from "all natural" ingredients (although the ingredients list changes depending on what website you visit). They have little or no scientific basis to back up the marketing claims, but the sales pitch is far from benign.

Dangerous health advice

David Bell lives in a retirement village in the northern suburbs of Melbourne.

He is well-educated — his hobby is translating Russian poets of the 19th and early 20th centuries into English — but David's health is poor and he has diabetes.

When an article supposedly penned by me popped up on his laptop it got his attention.

"I thought, 'this is interesting. I wonder what Norman's got to say about diabetes'," he told me.

"It was compelling. And what it was saying was that there is … a chemical called metformin, and it is not beneficial to the body. You should stop taking it."

Metformin is one of the core drugs used to treat type-2 diabetes and is effective in helping to prevent diabetes complications such as blindness and kidney damage.

The article encouraged diabetes patients to stop their metformin and start taking Glyco Balance instead.

The article was so convincing that David ceased his prescribed medication.

"You're a well-known figure in the health service. Why would I not believe you?"

Late in 2024, another ad for Glyco Balance with similar content appeared on Meta platforms.

This time, instead of me, it was an AI-generated video of leading diabetes researcher and specialist Jonathan Shaw, of the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne.

It was this deepfake that drew in Adelaide resident Janis as she sought to lose weight.

"I researched him … and saw that he was really high up in the heart and diabetes [medical space] in Australia," she told 7.30.

"So I thought, 'Wow this guy's put this product together. It's Australian. I'll give it a go.'"

When Janis's order arrived, the dose on the bottle was 204 milligrams, but the advertised amount was 800mg.

Her bank account also had more than $300 removed instead of just over $200 and eventually Janis discovered that the company had put in place a monthly debit of more than $300 without her being aware of it.

Even with all that, she did try the supplement to see what happened.

"Actually, as far as I'm talking about losing weight … I put on a few kilos while I was taking the first bottle," Janis told 7.30.

Tracking those responsible

7.30 has found three registered businesses linked to Glyco Balance and Keto Flow + ACV: Vellec Group NZ Ltd, Healthy Life Choices NZ Ltd and Apex United Pty Ltd.

They have offices in Christchurch and the Gold Coast, and appear to be connected to a global company based in the US.

They use the same sales and marketing playbook, the same website layout and the same deceptive tactics to lure in consumers.

7.30 has found that some of the people involved in running these companies are related to each other.

Numerous customers all have the same complaints about both products. Namely: people are being overcharged and signed up to a monthly auto-debit without their permission.

7.30 has emailed and phoned the companies involved and contacted their Auckland-based accountant. Apart from one person denying he had anything to do with the business despite being the sole registered director, we have had no other responses.

Since the businesses have been contacted, the main order pages for Glyco Balance have been taken down.

Affiliate websites now redirect customers to order pages for "Glucovate" and "Glyco Forte".

A search through internet archives reveals other name changes the product has undergone in the past, including Blood Balance — the version I was first deepfaked in relation to 18 months ago.

How deepfakes are made

These fakes are remarkably easy to make.

"You need a laptop, internet connection, access to some free or paid software, so it's not a capital-intensive business," said Sanjay Jha from UNSW's School of Computer Science and Engineering.

He and his student Wenbin Wang have developed an artificial intelligence model for teaching purposes. They showed us how the scammer likely created my deepfakes.

The scammer starts with a video of me, taken from a platform like YouTube. They then upload it to a deepfake program that can be purchased for a few dollars.

First, my voice is cloned from a sample which can be as short as a few seconds. The AI model then clones my appearance, scanning the video of me frame by frame, mapping my face from various angles. Then the scammer can type in what words they want me to say.

Meta's 'get-out' card

When Professor Shaw began to receive emails and calls from people wanting to stop their medication or wanting to know where they could get the supplement, he knew there was an issue.

His initial attempts to get Meta to take down the fake ad got nowhere until the Baker Institute's lawyers advised Meta there had been a breach of trademark and intellectual property.

That is when they got a response and had the scam taken down. But new versions kept on appearing.

The ABC has also had trouble getting the attention of Meta.

Rod McGuinness is the ABC's social community lead and coordinates the ABC's presence on social media. He has had over a dozen ABC personalities used by scammers, including Karl Kruszelnicki, Alan Kohler, Michael Rowland and Virginia Trioli.

"We spend a lot of time, or certainly have over the years, reporting these things, saying to Meta, 'can you do something about this?' And very often there's no response," McGuinness told 7.30.

In 2024, Meta made over $US164 billion, most of which was advertising revenue. Scammers exploit Facebook and Instagram's algorithms, targeting vulnerable consumers via paid posts.

Up until now, Meta has largely shirked responsibility. Mr McGuinness says he has been frustrated by its lack of responsibility.

"Facebook have always said they're not publishers — it's the people that use Facebook that are the publishers," he said.

"And I think in this context that's quite a nice get out because they can say, well, we don't control these things. However, they are happy to take the ad revenue."

Nathaniel Gleicher is the director of security policy and global head of counter fraud at Meta. He says the organisation faces a significant challenge.

"We're talking about sophisticated operations working at industrial scale, often backed by criminal organisations that are highly resourced … and are looking to target people wherever they can find them," Mr Gleicher said.

"They're very quick to adjust their tactics to defeat any defences you put in place."

He also maintains that Meta has been highly proactive in its approach to deepfake scams.

"In the fourth quarter of 2024 we removed more than a billion fake accounts and, 99.7 per cent of those, we removed proactively before anyone noticed them," he said.

But a miss rate of 0.3 per cent in more than a billion accounts means there are still a lot of scams slipping through.

"One of the real challenges is that these scams abuse multiple systems," Mr Gleicher said.

"The scammer starts by creating a fake bank account to receive the money — they often need a warehouse to store the actual products that they might be shipping [then] they will move people to a website on the open internet, and then, obviously, they're using an instant payment system.

"To counter this, you really need each of these communities working together."

Aussies lose more than $2 billion

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) runs the National Anti-Scam Centre.

ACCC deputy chair Catriona Lowe says that controlling these scams is complex and requires cooperation with local and international law enforcement and proactive work by carriers such as Meta.

"We have released a report that demonstrates an over 25 per cent decline in reported financial losses to scams during 2024, but with $2 billion lost, we still have plenty of work to do," she said.

New legislation has given the regulator the power to impose multimillion-dollar fines if platforms fail to remove scam content and these platforms are on notice.

"We anticipate that social media, including Meta, will be one of the early designated sectors," Ms Lowe said.

"That will mean that there will be financial penalties to that sector if they do not fulfil or take reasonable steps to fulfil their obligations under that law."

But that still leaves people like David and Janis to cope by themselves after getting scammed.

"I felt really shattered," Janis told 7.30.

"It was horrible, because I thought this was really real. So it took me back because I had thought I'd just bought this miracle drug."

Professor Shaw thinks the damage goes even deeper than the health and financial risks.

"What happens as a result of this and other similar things is mistrust," he said.

"Maybe all sorts of useful things that I and other people might say about health will not be trusted."

Watch 7.30, Mondays to Thursdays 7:30pm on ABC iview and ABC TV.

Written by Norman Swan, Hannah Meagher, ABC News.