Australia’s freight used to go by train, not truck. Here’s how we can bring back rail – and cut emissions

- Replies 7

Until the 1960s, railways dominated freight across every distance bar the shortest. Much freight went by sea, and some by truck.

But then trucking grew, and grew, and grew, while rail’s share of freight outside mined ore has shrunk and domestic shipping freight is diminished. By the mid-70s, trains carried only about 23% of domestic non-bulk freight (such as consumer goods) and trucks took 65.5%.

By 2021–22, trains took just 16.7% and trucks took almost 80%. Just 2% of freight between Melbourne and Sydney now goes by rail, while road freight is projected to keep growing.

That’s a problem, given heavy trucks are big emitters. Rail uses roughly a third of the diesel as a truck would to transport the same weight. Transport now accounts for 21% of Australia’s emissions. While electric cars and the long-awaited fuel efficiency standards are projected to cut this by seven million tonnes, trucking emissions are expected to keep growing.

It won’t be easy to change it. But if we improve sections of railway track on the east coast, we could at least make rail faster and more competitive.

Road freight has grown enormously due largely to non-bulk freight such as consumer goods. Freight carried by road has grown from about 29 billion tonne-kilometres in 1976–77 to 163 billion tonne-kilometres in 2021–22. (A tonne-kilometre measures the number of tonnes carried multiplied by distance). In that period, non-bulk freight carried by rail increased from about 10 to 34 billion tonne-kilometres.

Why? An official report gives key reasons such as expanding highway networks and higher capacity vehicles such as B-doubles.

Spending on roads across all levels of government is now more than A$30 billion a year.

Federal grants enabled the $20 billion reconstruction of the entire Hume Highway (Melbourne to Sydney), bringing it up to modern engineering standards. A similar sum was spent on reconstructing most of the Pacific Highway (Sydney to Brisbane).

What do our trains get? In 2021–22, the Australian Rail Track Corporation had a meagre $153 million to maintain its existing 7,500 kilometre interstate network.

This is separate from the 1,600km Inland Rail project which will link Melbourne to Brisbane via Parkes when complete. If the massive Inland Rail project is completed in the 2030s, it could potentially cut Australia’s freight emissions by 0.75 million tonnes a year by taking some freight off trucks. But this freight-only line is some way off – the first 770km between Beveridge in Victoria and Narromine in New South Wales is expected to be complete by 2027.

As a result, the authority maintaining Australia’s interstate rail tracks is “really struggling with maintenance, investment and building resilience”, according to federal Infrastructure Minister Catherine King.

This makes it harder for rail to compete, as Paul Scurrah, CEO of Pacific National, Australia’s largest private rail freight firm has said:

The need to cut freight emissions has been recognised by the Australian government, which has accelerated a review of the national freight and supply chain strategy.

To date, much attention in Australia and overseas has centred on finding ways to lower trucking emissions.

There are other ways. One is to shift some freight back to rail, which forms part of Victoria’s recent green freight strategy. This will be assisted by new intermodal terminals allowing containers to be offloaded from long-distance trains to trucks for the last part of their journey.

The second way is to improve rail freight energy efficiency. Western Australia’s long, heavy iron ore freight trains are already very energy efficient, and the introduction of battery electric locomotives will improve efficiency further. Our interstate rail freight on the eastern seaboard is much less efficient.

While the Inland Rail project is being built, we urgently need to upgrade the existing Melbourne–Sydney–Brisbane rail corridor, which has severe restrictions on speed.

To make this vital corridor better, there are three main sections of new track needed on the New South Wales line to replace winding or slow steam-age track. They’re not new – my colleagues and I first identified them more than 20 years ago.

These new sections are:

Track straightening on the Brisbane–Rockhampton line in the 1990s made it possible to run faster tilt trains and heavier, faster freight trains.

One challenge is who would build this. This year’s review of the Inland Rail project amid cost and time blowouts has raised questions over whether the ARTC is best placed to do so.

One thing is for sure: business as usual will mean more trucks carrying freight and more emissions. To actually tackle freight emissions will take policy reform on many fronts.

This article was first published on The Conversation and was written by Philip Laird Honorary Principal Fellow, University of Wollongong

But then trucking grew, and grew, and grew, while rail’s share of freight outside mined ore has shrunk and domestic shipping freight is diminished. By the mid-70s, trains carried only about 23% of domestic non-bulk freight (such as consumer goods) and trucks took 65.5%.

By 2021–22, trains took just 16.7% and trucks took almost 80%. Just 2% of freight between Melbourne and Sydney now goes by rail, while road freight is projected to keep growing.

That’s a problem, given heavy trucks are big emitters. Rail uses roughly a third of the diesel as a truck would to transport the same weight. Transport now accounts for 21% of Australia’s emissions. While electric cars and the long-awaited fuel efficiency standards are projected to cut this by seven million tonnes, trucking emissions are expected to keep growing.

It won’t be easy to change it. But if we improve sections of railway track on the east coast, we could at least make rail faster and more competitive.

How did road freight become dominant?

Since the 1970s, the volume of freight carried by Australia’s rail and road have both grown. But rail’s growth has largely been in bulk freight, such as the 895 million tonnes of iron ore and 338 million tonnes of coal exports in 2022–23.Road freight has grown enormously due largely to non-bulk freight such as consumer goods. Freight carried by road has grown from about 29 billion tonne-kilometres in 1976–77 to 163 billion tonne-kilometres in 2021–22. (A tonne-kilometre measures the number of tonnes carried multiplied by distance). In that period, non-bulk freight carried by rail increased from about 10 to 34 billion tonne-kilometres.

Why? An official report gives key reasons such as expanding highway networks and higher capacity vehicles such as B-doubles.

Spending on roads across all levels of government is now more than A$30 billion a year.

From freight trains to road trains: trucks have taken the throne from trains. Shutterstock

Federal grants enabled the $20 billion reconstruction of the entire Hume Highway (Melbourne to Sydney), bringing it up to modern engineering standards. A similar sum was spent on reconstructing most of the Pacific Highway (Sydney to Brisbane).

What do our trains get? In 2021–22, the Australian Rail Track Corporation had a meagre $153 million to maintain its existing 7,500 kilometre interstate network.

This is separate from the 1,600km Inland Rail project which will link Melbourne to Brisbane via Parkes when complete. If the massive Inland Rail project is completed in the 2030s, it could potentially cut Australia’s freight emissions by 0.75 million tonnes a year by taking some freight off trucks. But this freight-only line is some way off – the first 770km between Beveridge in Victoria and Narromine in New South Wales is expected to be complete by 2027.

As a result, the authority maintaining Australia’s interstate rail tracks is “really struggling with maintenance, investment and building resilience”, according to federal Infrastructure Minister Catherine King.

This makes it harder for rail to compete, as Paul Scurrah, CEO of Pacific National, Australia’s largest private rail freight firm has said:

Each year, billions in funding is hardcoded in federal and state government budgets to upgrade roads and highways, which then spurs on greater access for bigger and heavier trucks […] Rail freight operators pay ‘full freight’ rates to run on tracks plagued by pinch points, speed restrictions, weight limits, sections susceptible to frequent flooding, and a lack of passing opportunities on networks shared with passenger services

What would it take to make rail more viable?

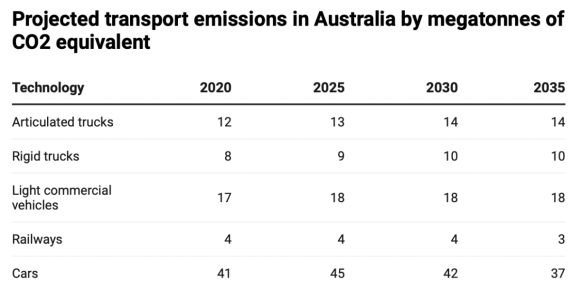

By 2030, road freight emissions are expected to increase from 37 to 42 million tonnes, while railway emissions stay steady at four million tonnes.The need to cut freight emissions has been recognised by the Australian government, which has accelerated a review of the national freight and supply chain strategy.

To date, much attention in Australia and overseas has centred on finding ways to lower trucking emissions.

There are other ways. One is to shift some freight back to rail, which forms part of Victoria’s recent green freight strategy. This will be assisted by new intermodal terminals allowing containers to be offloaded from long-distance trains to trucks for the last part of their journey.

The second way is to improve rail freight energy efficiency. Western Australia’s long, heavy iron ore freight trains are already very energy efficient, and the introduction of battery electric locomotives will improve efficiency further. Our interstate rail freight on the eastern seaboard is much less efficient.

For Queensland’s Brisbane to Bundaberg tilt train to operate, the tracks had to be straightened and upgraded. AAP

While the Inland Rail project is being built, we urgently need to upgrade the existing Melbourne–Sydney–Brisbane rail corridor, which has severe restrictions on speed.

To make this vital corridor better, there are three main sections of new track needed on the New South Wales line to replace winding or slow steam-age track. They’re not new – my colleagues and I first identified them more than 20 years ago.

These new sections are:

- Wentworth – about 40km of track stretching from near Macarthur to Mittagong

- Centennial – about 70km of track from near Goulburn to Yass

- Hoare – about 80km of track from near Yass to Cootamundra.

Track straightening on the Brisbane–Rockhampton line in the 1990s made it possible to run faster tilt trains and heavier, faster freight trains.

One challenge is who would build this. This year’s review of the Inland Rail project amid cost and time blowouts has raised questions over whether the ARTC is best placed to do so.

One thing is for sure: business as usual will mean more trucks carrying freight and more emissions. To actually tackle freight emissions will take policy reform on many fronts.

This article was first published on The Conversation and was written by Philip Laird Honorary Principal Fellow, University of Wollongong