Australians’ satisfaction with life is at its lowest level in two decades

- Replies 7

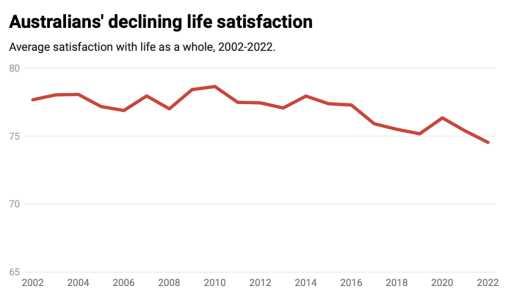

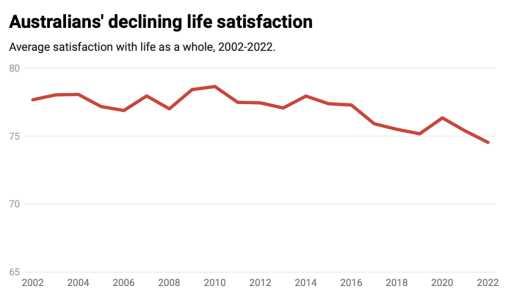

Australians’ satisfaction with life as a whole is at its lowest level in 21 years, according to the latest Australian Unity Wellbeing Index survey, a collaboration between Deakin University and mutual company Australian Unity.

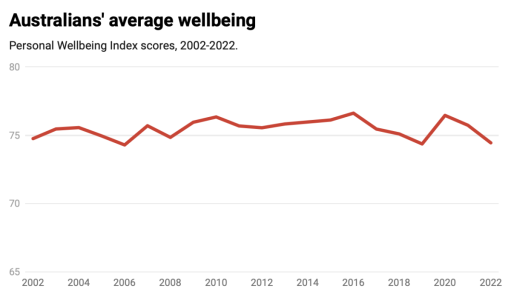

Each year since 2001, we survey a geographically representative sample of 2,000 Australians about how satisfied they are with their lives as a whole, along with their satisfaction with seven key life areas to compile an overall measure: the Personal Wellbeing Index.

Our survey was conducted in May and June of 2022, by which time inflation was exceeding 6% and the Reserve Bank of Australia had delivered the first two of ten consecutive interest rate rises. There have now been 11 since May 2022.

In 2020, at the start of the pandemic, we actually saw an improvement in satisfaction with life as a whole. The decline since likely reflects pressures like cost of living but also conforms with a longer-term trend since 2010.

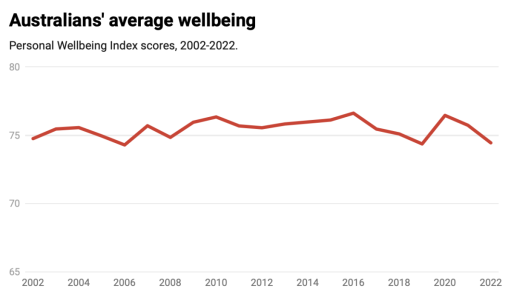

This composite has been pretty stable over the survey’s 21 years, with average scores ranging between 74 and 77.

But small shifts are significant because we do not expect to ever see big ones. This is due, principally, to a type of “psychological homeostasis” whereby most people will ride out the highs and lows of their lives and maintain a relatively positive outlook regardless of the circumstances.

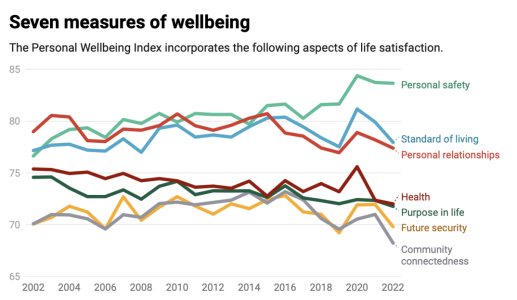

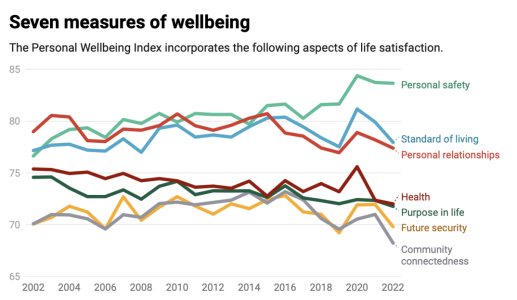

Also, as an average, different factors can counterbalance each other. You can get a better sense of this from the following graph, which shows the constituent elements of the Personal Wellbeing Index.

This shows a long-term increase in feelings of personal safety but long-term declines in the average measures of health and purpose in life, with relatively steep declines since 2021 in standard of living, future security and community connectedness.

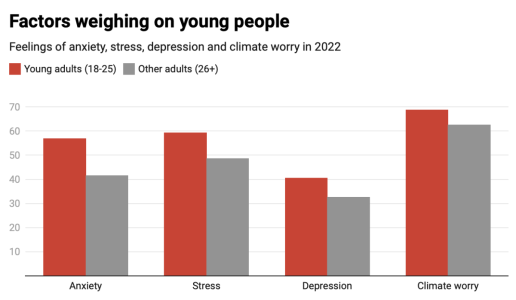

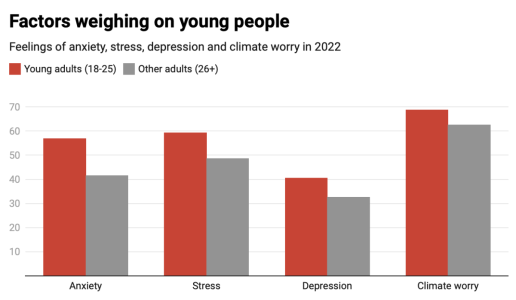

The average wellbeing score for 18- to 25-year-olds was the lowest in 21 years. It likely reflects higher feelings of anxiety, stress, depression and climate worry (also measured in our survey) among this age group.

It underscores the importance of considering wellbeing in policy decisions, particularly for groups that are struggling the most.

As Treasurer Jim Chalmers noted in his lengthy essay in The Monthly in February, we must “build something better” in the face of ongoing crises.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Kate Lycett, NHMRC Early Career Fellow, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Georgie Frykberg, Project Coordinator, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Mallery Crowe, Epidemiologist & Project Officer, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Tanja Capic, PhD candidate, Psychology, Deakin University

Each year since 2001, we survey a geographically representative sample of 2,000 Australians about how satisfied they are with their lives as a whole, along with their satisfaction with seven key life areas to compile an overall measure: the Personal Wellbeing Index.

Our survey was conducted in May and June of 2022, by which time inflation was exceeding 6% and the Reserve Bank of Australia had delivered the first two of ten consecutive interest rate rises. There have now been 11 since May 2022.

In 2020, at the start of the pandemic, we actually saw an improvement in satisfaction with life as a whole. The decline since likely reflects pressures like cost of living but also conforms with a longer-term trend since 2010.

The Y axis shows strength of feelings (out of 100).

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Measuring personal wellbeing

Our composite measure, the Personal Wellbeing Index, incorporates seven life areas: standard of living, relationships, purpose in life, community connectedness, safety, health and future security. We combine these using an internationally regarded method to generate an index score out of 100.

The Y axis shows strength of feelings (out of 100).

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

This composite has been pretty stable over the survey’s 21 years, with average scores ranging between 74 and 77.

But small shifts are significant because we do not expect to ever see big ones. This is due, principally, to a type of “psychological homeostasis” whereby most people will ride out the highs and lows of their lives and maintain a relatively positive outlook regardless of the circumstances.

Also, as an average, different factors can counterbalance each other. You can get a better sense of this from the following graph, which shows the constituent elements of the Personal Wellbeing Index.

This shows a long-term increase in feelings of personal safety but long-term declines in the average measures of health and purpose in life, with relatively steep declines since 2021 in standard of living, future security and community connectedness.

The Y axis shows strength of feelings (out of 100).

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

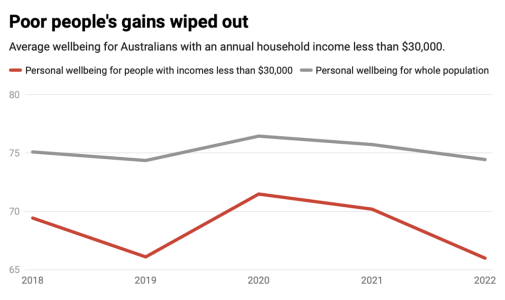

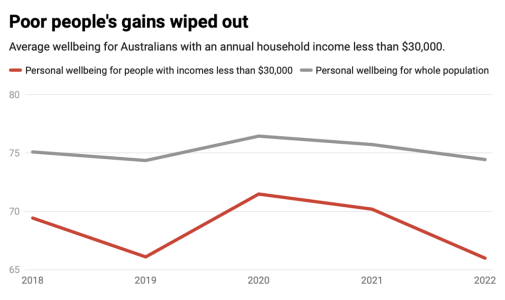

Wellbeing and low incomes

For Australia’s poor, 2020 unexpectedly had a silver lining when the federal government temporarily doubled JobSeeker payments. This likely explains the jump in wellbeing scores recorded in 2020 for those with household incomes of less than $30,000. But with those extra payments ending (in March 2021) and the increases in living costs since, the average wellbeing score for poor people has plummeted.

The Y axis shows strength of feelings (out of 100).

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Differences by age

Those aged 76 and older reported the highest average wellbeing (78.7 out of 100), and those aged 18-25 the lowest – though not by much, with their score (72.5) being just below those aged 46-55 years (73.2).The average wellbeing score for 18- to 25-year-olds was the lowest in 21 years. It likely reflects higher feelings of anxiety, stress, depression and climate worry (also measured in our survey) among this age group.

The Y axis shows strength of feelings (out of 100).

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Chart: The Conversation Source: Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Creating a wellbeing economy

Given the ongoing uncertainties and cost-of-living pressures that we now face, there’s every reason to expect Australians’ wellbeing to now be even lower than when our survey was conducted.It underscores the importance of considering wellbeing in policy decisions, particularly for groups that are struggling the most.

As Treasurer Jim Chalmers noted in his lengthy essay in The Monthly in February, we must “build something better” in the face of ongoing crises.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Kate Lycett, NHMRC Early Career Fellow, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Georgie Frykberg, Project Coordinator, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Mallery Crowe, Epidemiologist & Project Officer, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Tanja Capic, PhD candidate, Psychology, Deakin University