Australian scientists aiming to grow plants on the moon prepare for launch of Lunaria One

By

ABC News

- Replies 0

An Australian team attempting to grow plants on the moon is finalising a prototype designed to carry an assortment of plants and seeds to the lunar surface.

If the plants and seeds survive the journey, the team is hoping they will be able to thrive on the moon's surface.

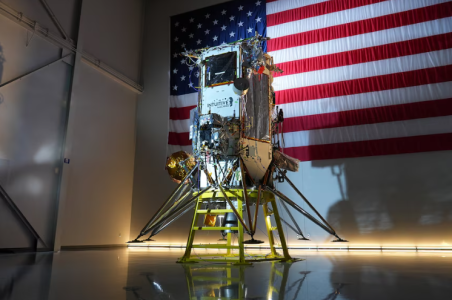

The project, which is being headed by Australian company Lunaria One, will hitch a ride on the exterior of a lander built by USA-based Intuitive Machines, and is currently scheduled to launch in March or April 2026.

The goal of the mission is to discover how plants and seeds respond to the low-levels of gravity on the moon.

Mission lead Lauren Fell said the project was intended to be the first step down a path that would eventually allow humans to have a sustainable presence on the moon.

To achieve this goal, Lunaria One, along with partners from industry and universities, has developed a bio-module capable of keeping the plants warm, while keeping the harsh vacuum environment of space out.

Under current time frames, Lunaria One's bio-module and plants have to be ready for installation on the lunar lander that will carry them to the surface of the moon by the end of the year.

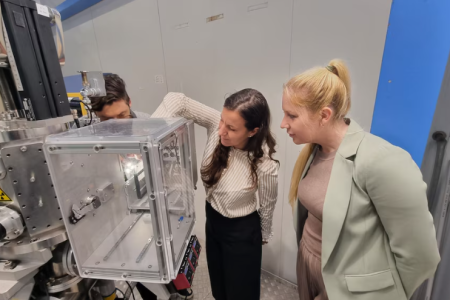

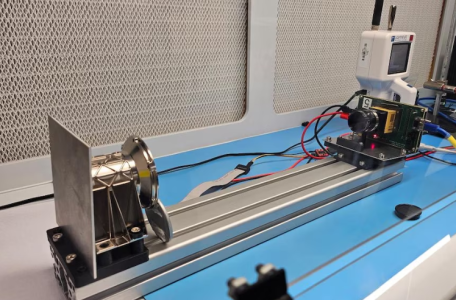

A prototype built at RMIT University in Melbourne is being tested to make sure it can handle the high vibration and temperatures it will be subjected to during launch, as well as the potential radiation and temperature extremes it can experience in space.

At the Centre for Accelerator Science nuclear lab in Lucas Heights near Sydney, another team is investigating which plant species to send into space.

No guarantees plants will survive trip to moon

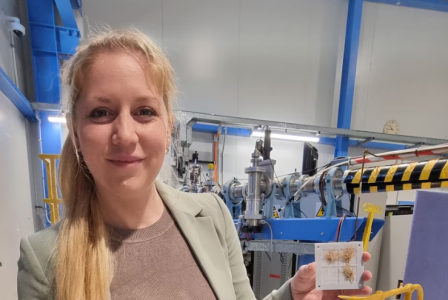

In a small plastic box, seeds and plants were bombarded with radiation equivalent to four days, eight days and five years on the lunar surface.

"We are testing to see where those boundaries are," Ms Fell said.

"Life is very resilient, and we have chosen species on purpose that have a lot of resilience – lichens for example have been shown to survive outside the International Space Station."

The mission, named the Australian Lunar Experiment Promoting Horticulture, or ALEPH, is backed by a $3.6 million grant from the Australian Space Agency’s Moon to Mars Demonstrator Mission Grants, with contributions from industry.

It is hoped the mission will help incubate a domestic space industry, with the team developing as much of the equipment onshore as possible.

Big plans for small module

One headache for scientists trying to get the plants to survive the trip to the moon is the weight limit.

The entire project can only weigh 500 grams.

Within that limit they must accommodate the pressurised bio-module, internal heating system, electronics, sensors, lighting, water, the plants themselves, and a space-rated camera that will watch for growth.

Professor Caitlin Byrt, a biologist consultant on the team, was blunt about the plants' survival chances.

There would be many things that could kill them on the journey, she said, including massive shaking at take-off, solar radiation, temperatures hundreds of degrees above boiling and below freezing, risk of module breach and water venting into space.

"People in their homes all around the world wonder why their house plant has died — and that's in quite comfortable conditions," she said.

"I think it's going to be a huge challenge to have something that's still kicking with life by the time it gets to the moon."

A lunar day lasts about two weeks, and after touching down in the lunar dawn, the plants have about 72 hours to live before the environment simply becomes too hot.

"After that it's show over," Professor Byrt said.

"A little sprout growing — that's what I dream of, that's what I'd love to see."

'A human story of exploration'

The mission was not an idle curiosity, Professor Byrt said, and may have applications back on Earth.

Just as tech developed for the International Space Station led to better water recycling here, she said ALEPH could teach people how to grow food in inhospitable locations or after disasters.

"Imagine if you could deliver systems that are super well optimised despite challenging conditions, that communities can use to be growing plants and supplying their own food," she said.

Studies of microbes on the International Space Station showed new "alien" varieties had developed, and Dr Byrt said it was "probably inevitable" efforts to grow plants on the moon would create unique organisms, as nature found a way to balance a new closed ecosystem.

ALEPH is hoped to be the first in a series of planned missions, all working towards human habitation on the moon, with subsequent missions to go for longer durations and carry more biomaterial.

Intuitive Machines's chief technology officer Dr Tim Crain said what happened to plants at lunar gravity was almost completely unknown.

"We've done a lot of experiments on the International Space Station for micro gravity, to see how living things respond to zero [gravity]. But this is an opportunity to see one-sixth gravity — does it inhibit growth, does it promote growth?" Dr Crain said.

"Can we take the plant life we need with us out into the solar system and co-exist with it?"

"It's a human story of exploration and we are proud that Australia is a part of that."

Project linked to school curriculum

ALEPH will be carried on Intuitive Machines's third lunar lander, and Dr Crain said the team needed three months to integrate the bio-module and install the lander on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

As well as growing a domestic space industry, there were plans to use ALEPH to teach kids science at home.

Lunaria One has partnered with science education company Stile Education to develop kits that could be sent to schools, allowing students to see whether different plants would grow in similar conditions to the moon.

"It's curriculum-aligned so teachers will be able to know it works into the curriculum," Ms Fell said.

"We want to make an Australia-wide connection to the project."

Written by Geraden Cann, ABC News.

If the plants and seeds survive the journey, the team is hoping they will be able to thrive on the moon's surface.

The project, which is being headed by Australian company Lunaria One, will hitch a ride on the exterior of a lander built by USA-based Intuitive Machines, and is currently scheduled to launch in March or April 2026.

The goal of the mission is to discover how plants and seeds respond to the low-levels of gravity on the moon.

Mission lead Lauren Fell said the project was intended to be the first step down a path that would eventually allow humans to have a sustainable presence on the moon.

To achieve this goal, Lunaria One, along with partners from industry and universities, has developed a bio-module capable of keeping the plants warm, while keeping the harsh vacuum environment of space out.

Under current time frames, Lunaria One's bio-module and plants have to be ready for installation on the lunar lander that will carry them to the surface of the moon by the end of the year.

A prototype built at RMIT University in Melbourne is being tested to make sure it can handle the high vibration and temperatures it will be subjected to during launch, as well as the potential radiation and temperature extremes it can experience in space.

At the Centre for Accelerator Science nuclear lab in Lucas Heights near Sydney, another team is investigating which plant species to send into space.

In a small plastic box, seeds and plants were bombarded with radiation equivalent to four days, eight days and five years on the lunar surface.

"We are testing to see where those boundaries are," Ms Fell said.

"Life is very resilient, and we have chosen species on purpose that have a lot of resilience – lichens for example have been shown to survive outside the International Space Station."

The mission, named the Australian Lunar Experiment Promoting Horticulture, or ALEPH, is backed by a $3.6 million grant from the Australian Space Agency’s Moon to Mars Demonstrator Mission Grants, with contributions from industry.

It is hoped the mission will help incubate a domestic space industry, with the team developing as much of the equipment onshore as possible.

Big plans for small module

One headache for scientists trying to get the plants to survive the trip to the moon is the weight limit.

The entire project can only weigh 500 grams.

Within that limit they must accommodate the pressurised bio-module, internal heating system, electronics, sensors, lighting, water, the plants themselves, and a space-rated camera that will watch for growth.

Professor Caitlin Byrt, a biologist consultant on the team, was blunt about the plants' survival chances.

There would be many things that could kill them on the journey, she said, including massive shaking at take-off, solar radiation, temperatures hundreds of degrees above boiling and below freezing, risk of module breach and water venting into space.

"People in their homes all around the world wonder why their house plant has died — and that's in quite comfortable conditions," she said.

"I think it's going to be a huge challenge to have something that's still kicking with life by the time it gets to the moon."

A lunar day lasts about two weeks, and after touching down in the lunar dawn, the plants have about 72 hours to live before the environment simply becomes too hot.

"After that it's show over," Professor Byrt said.

"A little sprout growing — that's what I dream of, that's what I'd love to see."

The mission was not an idle curiosity, Professor Byrt said, and may have applications back on Earth.

Just as tech developed for the International Space Station led to better water recycling here, she said ALEPH could teach people how to grow food in inhospitable locations or after disasters.

"Imagine if you could deliver systems that are super well optimised despite challenging conditions, that communities can use to be growing plants and supplying their own food," she said.

Studies of microbes on the International Space Station showed new "alien" varieties had developed, and Dr Byrt said it was "probably inevitable" efforts to grow plants on the moon would create unique organisms, as nature found a way to balance a new closed ecosystem.

ALEPH is hoped to be the first in a series of planned missions, all working towards human habitation on the moon, with subsequent missions to go for longer durations and carry more biomaterial.

Intuitive Machines's chief technology officer Dr Tim Crain said what happened to plants at lunar gravity was almost completely unknown.

"We've done a lot of experiments on the International Space Station for micro gravity, to see how living things respond to zero [gravity]. But this is an opportunity to see one-sixth gravity — does it inhibit growth, does it promote growth?" Dr Crain said.

"Can we take the plant life we need with us out into the solar system and co-exist with it?"

"It's a human story of exploration and we are proud that Australia is a part of that."

Project linked to school curriculum

ALEPH will be carried on Intuitive Machines's third lunar lander, and Dr Crain said the team needed three months to integrate the bio-module and install the lander on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

As well as growing a domestic space industry, there were plans to use ALEPH to teach kids science at home.

Lunaria One has partnered with science education company Stile Education to develop kits that could be sent to schools, allowing students to see whether different plants would grow in similar conditions to the moon.

"It's curriculum-aligned so teachers will be able to know it works into the curriculum," Ms Fell said.

"We want to make an Australia-wide connection to the project."

Written by Geraden Cann, ABC News.