Are Australian children being preyed on by aggressive junk food ads? Study reveals shocking results

In a world where childhood obesity is a growing concern, a recent study has revealed a disturbing trend in Australia.

Children are being subjected to aggressive marketing tactics promoting foods that are considered too unhealthy for young people in many other countries.

This alarming revelation calls for a serious re-evaluation of our food marketing regulations and a stronger commitment to safeguarding the health of our future generations.

The study, led by researchers at the George Institute for Global Health and published in Public Health Nutrition, has shown a direct correlation between packaged foods with low nutritional value and high use of marketing directed at children.

The findings are startling: over 95 per cent of these foods, which employ techniques directly marketed to children in Australia, would be banned in Mexico due to their unhealthy nature.

In 2020, Mexico mandated warning labels for food products exceeding energy, salt, fat, and sugar thresholds.

Foods carrying any warning label cannot be marketed to children on the packaging or other media advertising.

This progressive move has been hailed as a significant step towards combating childhood obesity and promoting healthier eating habits among young people.

In stark contrast, Australia's food marketing regulations only offer voluntary guidelines and do not include any restrictions on supermarkets regarding the use of characters and celebrities, graphics, giveaways, and competitions on packaging that appeal to children.

This lack of regulation allows the food industry to exploit children's emotional connection with characters and their biological preference for sweet and salty foods, leading to unhealthy eating habits.

Professor Simone Pettigrew, a senior author of the study, warned that this unregulated marketing directed at children, combined with the food industry's exploitation of kids’ 'pester power', is a public health disaster in the making.

'Pester power' refers to children's influence on their parents' purchasing decisions, particularly in supermarkets.

The study also highlighted that the unprecedented availability and aggressive marketing of ultra-processed, packaged foods and beverages is a key driver of childhood obesity.

With approximately one in four Australian children and adolescents affected by overweight and obesity, this is a pressing issue that demands immediate attention.

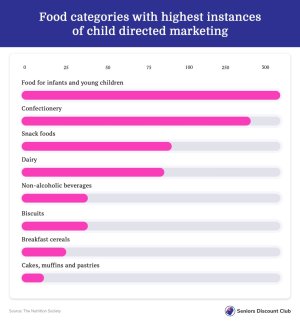

The researchers analysed over 8,000 products across eight categories selected because they had more child-directed promotions on their packaging. These included Nestle Milo Duo, Nutri-Grain cereal, Bega Stringers cheese sticks, Haribo Starmix and Doritos corn chips.

The study found that more than one in ten (11.3 per cent) products displayed at least one marketing technique directed at children. The most common technique used was personified characters, followed by references to childhood life, such as 'fun' and the depiction of playground equipment.

The healthiness of products using child-directed marketing was assessed using four measures—the Australian Health Star Rating system, the NOVA classification system for degree of processing, the World Health Organisation’s nutrient profiling model for the Western Pacific Region and the Mexican nutrient profiling model.

Products using child-directed promotional techniques received poor scores on all four indicators.

If Australia adopted similar legislation to Mexico, 95.5 per cent of products would have to remove their current child-directed marketing elements.

While Australia has a health star rating system rather than warning labels like Mexico, the same principle could be applied: 'You set a threshold, and you say these foods are not healthy enough to be marketed to children,' suggested Professor Pettigrew.

Terry Slevin, the Chief Executive of the Public Health Association of Australia, echoed this sentiment, stating that Australia needs to follow the lead of other countries regulating against unhealthy foods being marketed to children.

He believed that regulation was the only way to stop this harmful practice.

‘This research points to the tricks [the] industry uses, particularly to kids. It sets them on the wrong path nutritionally, contributing to rates of overweight and obesity, as well as contributing to a tsunami of chronic diseases we see in our hospitals,’ he explained.

Independent MP for Mackellar, Sophie Scamps, a former GP, introduced the Healthy Kids Advertising Bill 2023 to parliament in June to protect children from junk food marketing.

'The George Institute’s latest research is further evidence that food companies are deliberately targeting children in their marketing of unhealthy foods,' Ms Scamps pointed out.

‘It’s time government stepped in … to create an environment for our children to thrive in, not one where they are preyed upon for profit and paying for it with their health,’ she added.

What are your thoughts on this issue, members? Have you noticed these marketing tactics? How do you promote healthy eating habits in your grandchildren? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.

Children are being subjected to aggressive marketing tactics promoting foods that are considered too unhealthy for young people in many other countries.

This alarming revelation calls for a serious re-evaluation of our food marketing regulations and a stronger commitment to safeguarding the health of our future generations.

The study, led by researchers at the George Institute for Global Health and published in Public Health Nutrition, has shown a direct correlation between packaged foods with low nutritional value and high use of marketing directed at children.

The findings are startling: over 95 per cent of these foods, which employ techniques directly marketed to children in Australia, would be banned in Mexico due to their unhealthy nature.

In 2020, Mexico mandated warning labels for food products exceeding energy, salt, fat, and sugar thresholds.

Foods carrying any warning label cannot be marketed to children on the packaging or other media advertising.

This progressive move has been hailed as a significant step towards combating childhood obesity and promoting healthier eating habits among young people.

In stark contrast, Australia's food marketing regulations only offer voluntary guidelines and do not include any restrictions on supermarkets regarding the use of characters and celebrities, graphics, giveaways, and competitions on packaging that appeal to children.

This lack of regulation allows the food industry to exploit children's emotional connection with characters and their biological preference for sweet and salty foods, leading to unhealthy eating habits.

Professor Simone Pettigrew, a senior author of the study, warned that this unregulated marketing directed at children, combined with the food industry's exploitation of kids’ 'pester power', is a public health disaster in the making.

'Pester power' refers to children's influence on their parents' purchasing decisions, particularly in supermarkets.

The study also highlighted that the unprecedented availability and aggressive marketing of ultra-processed, packaged foods and beverages is a key driver of childhood obesity.

With approximately one in four Australian children and adolescents affected by overweight and obesity, this is a pressing issue that demands immediate attention.

The researchers analysed over 8,000 products across eight categories selected because they had more child-directed promotions on their packaging. These included Nestle Milo Duo, Nutri-Grain cereal, Bega Stringers cheese sticks, Haribo Starmix and Doritos corn chips.

The study found that more than one in ten (11.3 per cent) products displayed at least one marketing technique directed at children. The most common technique used was personified characters, followed by references to childhood life, such as 'fun' and the depiction of playground equipment.

The healthiness of products using child-directed marketing was assessed using four measures—the Australian Health Star Rating system, the NOVA classification system for degree of processing, the World Health Organisation’s nutrient profiling model for the Western Pacific Region and the Mexican nutrient profiling model.

Products using child-directed promotional techniques received poor scores on all four indicators.

If Australia adopted similar legislation to Mexico, 95.5 per cent of products would have to remove their current child-directed marketing elements.

While Australia has a health star rating system rather than warning labels like Mexico, the same principle could be applied: 'You set a threshold, and you say these foods are not healthy enough to be marketed to children,' suggested Professor Pettigrew.

Terry Slevin, the Chief Executive of the Public Health Association of Australia, echoed this sentiment, stating that Australia needs to follow the lead of other countries regulating against unhealthy foods being marketed to children.

He believed that regulation was the only way to stop this harmful practice.

‘This research points to the tricks [the] industry uses, particularly to kids. It sets them on the wrong path nutritionally, contributing to rates of overweight and obesity, as well as contributing to a tsunami of chronic diseases we see in our hospitals,’ he explained.

Independent MP for Mackellar, Sophie Scamps, a former GP, introduced the Healthy Kids Advertising Bill 2023 to parliament in June to protect children from junk food marketing.

'The George Institute’s latest research is further evidence that food companies are deliberately targeting children in their marketing of unhealthy foods,' Ms Scamps pointed out.

‘It’s time government stepped in … to create an environment for our children to thrive in, not one where they are preyed upon for profit and paying for it with their health,’ she added.

Key Takeaways

- Australian children are being exposed to aggressive marketing of unhealthy food, which would be banned in many other countries, according to a new study by the George Institute for Global Health.

- The study revealed that over 95 per cent of foods directly marketed to children in Australia would be banned in Mexico, which has strict food product warning labels.

- Australia's food marketing regulations are voluntary, with no restrictions on supermarkets such as using appealing techniques to promote unhealthy food to children.

- Independent MP for Mackellar, Sophie Scamps, a former GP, introduced the Healthy Kids Advertising Bill 2023 to parliament in June to protect children from junk food marketing.

What are your thoughts on this issue, members? Have you noticed these marketing tactics? How do you promote healthy eating habits in your grandchildren? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments below.