Ageing in a housing crisis: growing numbers of older Australians are facing a bleak future

- Replies 10

The collision between an ageing population and a housing crisis has left more older people in Australia enduring housing insecurity and homelessness. Our research, released today, explores how the scale of these problems among older people has grown over the past decade.

Our report, Ageing in a Housing Crisis, shows safe, secure and affordable housing is increasingly beyond the reach of older people. This growing housing insecurity is system-wide. It’s affecting hundreds of thousands of people across all tenures, including home owners and renters.

The federal government released Australia’s first national wellbeing framework, Measuring What Matterslast month. It recognises “financial security and access to housing” as essential for a secure, inclusive and fair society. However, urgent policy action is needed to reshape the Australian housing system so all older people have secure, affordable housing.

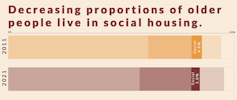

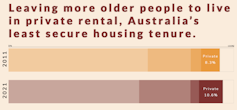

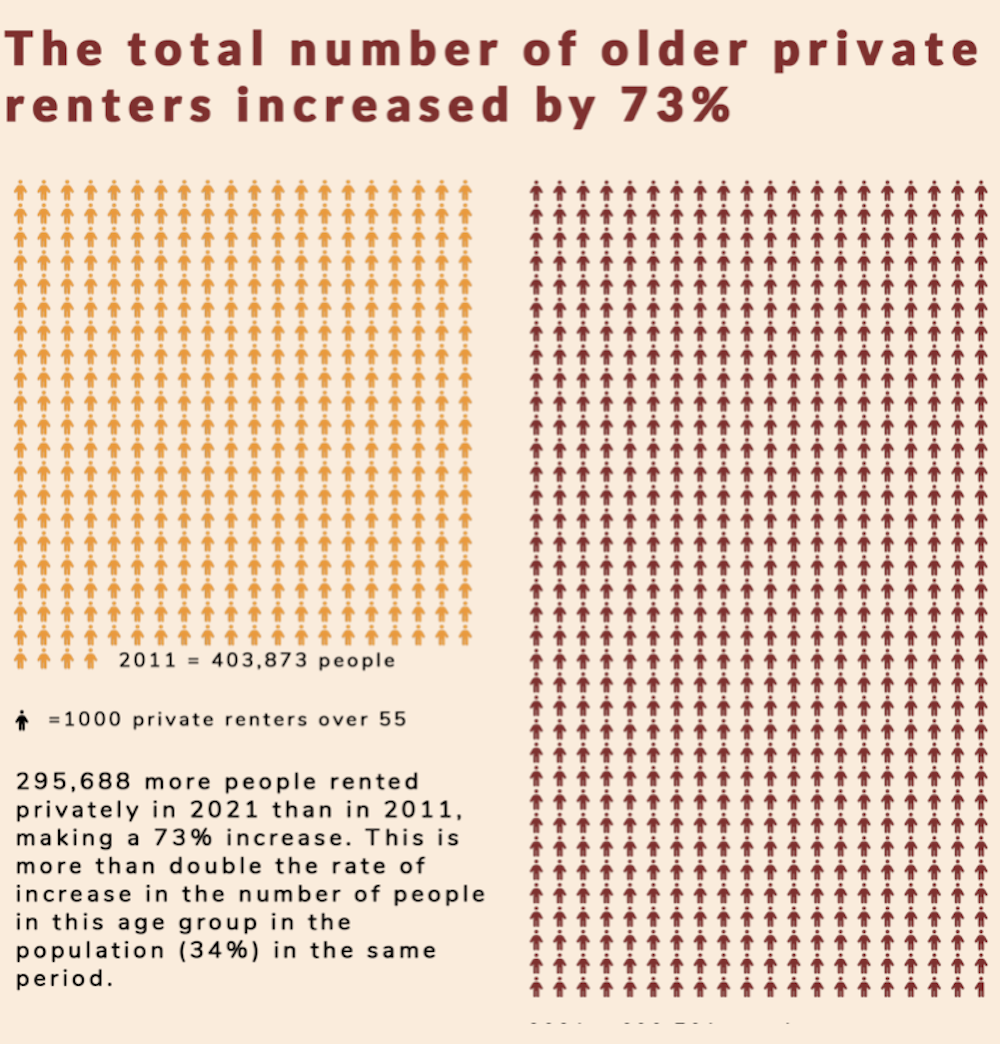

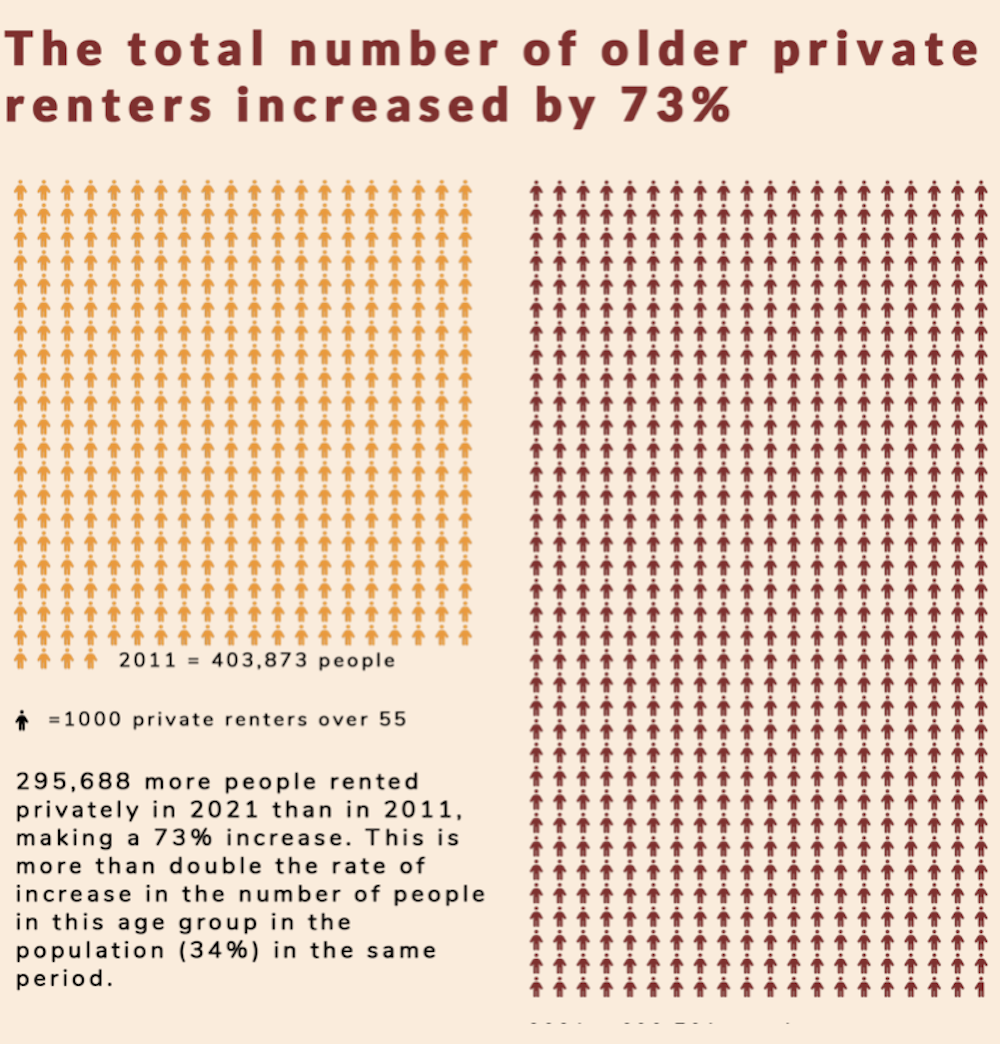

The proportion of older people in private rental housing has also increased. This means more older people are exposed to the insecurity of renting and rising rents. Our work shows they are struggling to afford private rental housing.

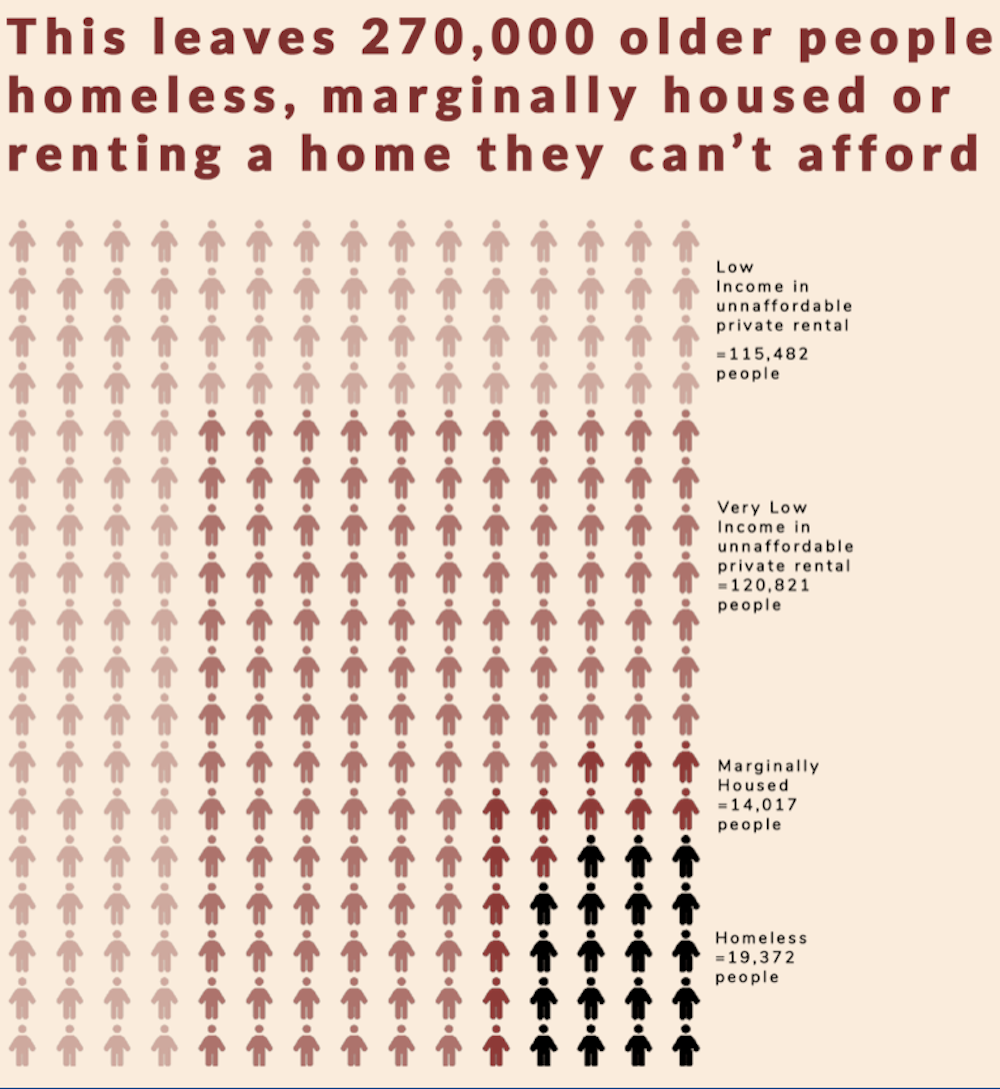

The lowest-income households are the hardest hit. The private rental market is failing to supply housing they can afford. The shortfall in subsidised social housing is huge.

Older people who receive government benefits and allowances are at most risk because their incomes are not keeping up with housing costs.

In 2019-20 only 19% of older people on very low incomes (the lowest 20% of household incomes) lived in households whose rent was affordable. This means four out of five were spending more than 30% of their income on rent (the affordability benchmark for low-income households). Two in five were paying severely unaffordable rents – more than 50% of their income.

For older people who don’t own their homes, rising housing prices create financial risk rather than windfall. At the same time, more older people have mortgages. This increases their risk of housing insecurity or financial stress in retirement.

Insecure or marginal housing affects all generations. However, for older people the risks are made worse by limited income-earning ability, increasing frailty, illness and/or caring responsibilities, growing need for at-home support, and age-based discrimination. These factors make it even harder to meet rising housing costs.

Housing insecurity widens the gap between the housing older people have and the housing they need to live safe, secure and dignified lives as they age.

We call for:

Responses and assistance models must allow for gender diversity, income difference, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people’s cultural needs, as well as those of other culturally and linguistically diverse older people. Disability, caring responsibilities, history of trauma, and individuals’ unique housing pathways and experiences must all be considered.

Older people must have a say in reshaping the housing system. The Albanese government is developing a National Housing and Homelessness Plan. It’s essential that this plan, along with state, territory and local government implementation plans, consider the voices, experiences, concerns and aspirations of older people.

Housing insecurity and homelessness in childhood, younger years and early adult life all warrant meaningful and urgent housing solutions. Making sure all people have lifelong access to secure housing will begin to reverse the growing problems identified by our report. Otherwise, Australia faces a future where more and more older people struggle with inadequate and unaffordable housing.

National reform that includes a focus on generational needs can deliver a housing system that provides affordable homes for everyone. This will ensure everyone is able to maintain community connections, which for older people means being able to age in safe, secure and affordable homes.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Emma Power, Associate Professor, Geography and Urban Studies, Western Sydney University, Amity James, Associate Professor and Discipline Lead Property, Curtin University, Francesca Perugia, Senior Lecturer, School of Design and the Built Environment, Curtin University, Margaret Reynolds, Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology, Piret Veeroja, Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology, Wendy Stone, Professor of Housing & Social Policy, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology

Our report, Ageing in a Housing Crisis, shows safe, secure and affordable housing is increasingly beyond the reach of older people. This growing housing insecurity is system-wide. It’s affecting hundreds of thousands of people across all tenures, including home owners and renters.

The federal government released Australia’s first national wellbeing framework, Measuring What Matterslast month. It recognises “financial security and access to housing” as essential for a secure, inclusive and fair society. However, urgent policy action is needed to reshape the Australian housing system so all older people have secure, affordable housing.

Authors & Housing for the Aged Action Group

Older people are increasingly at risk

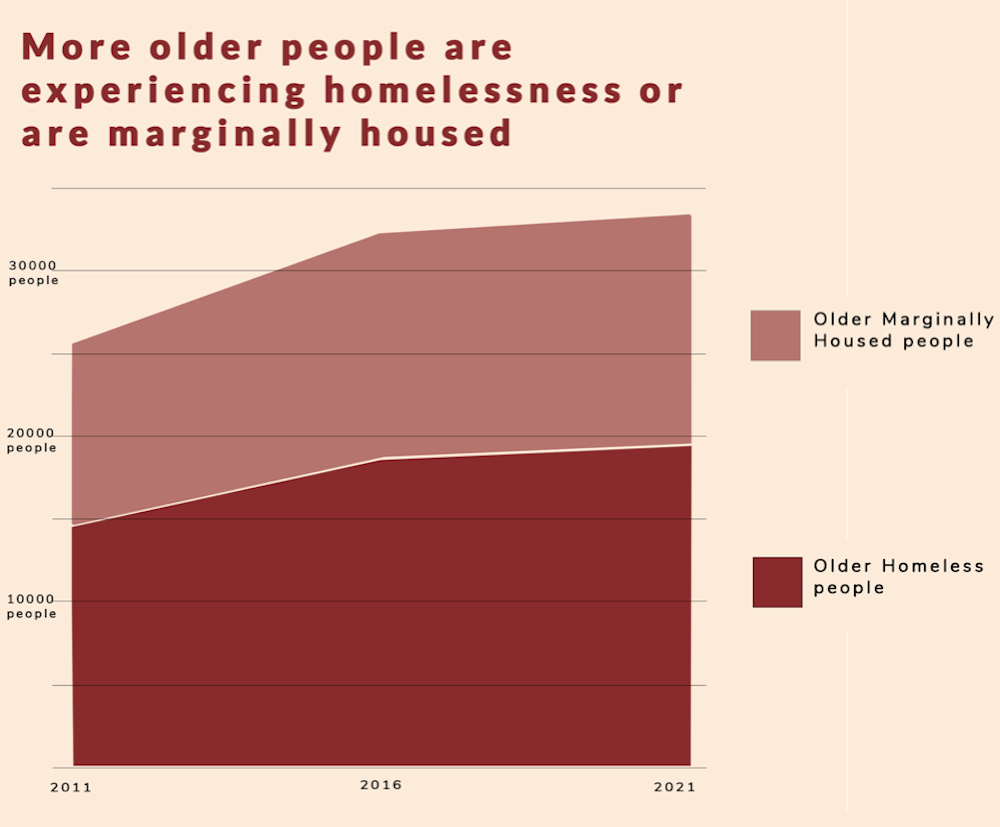

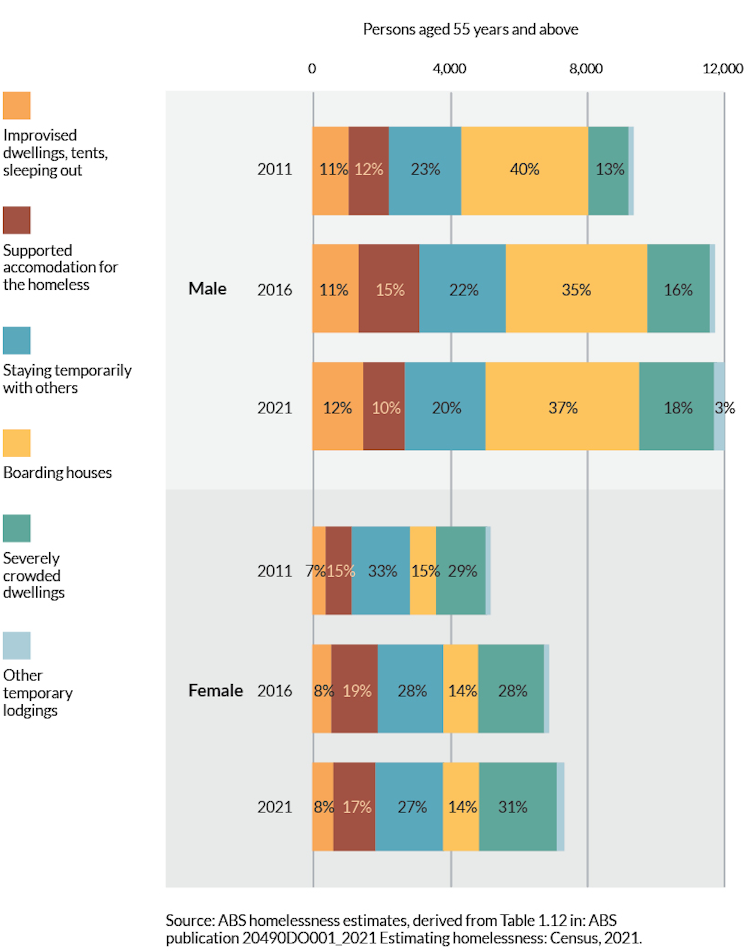

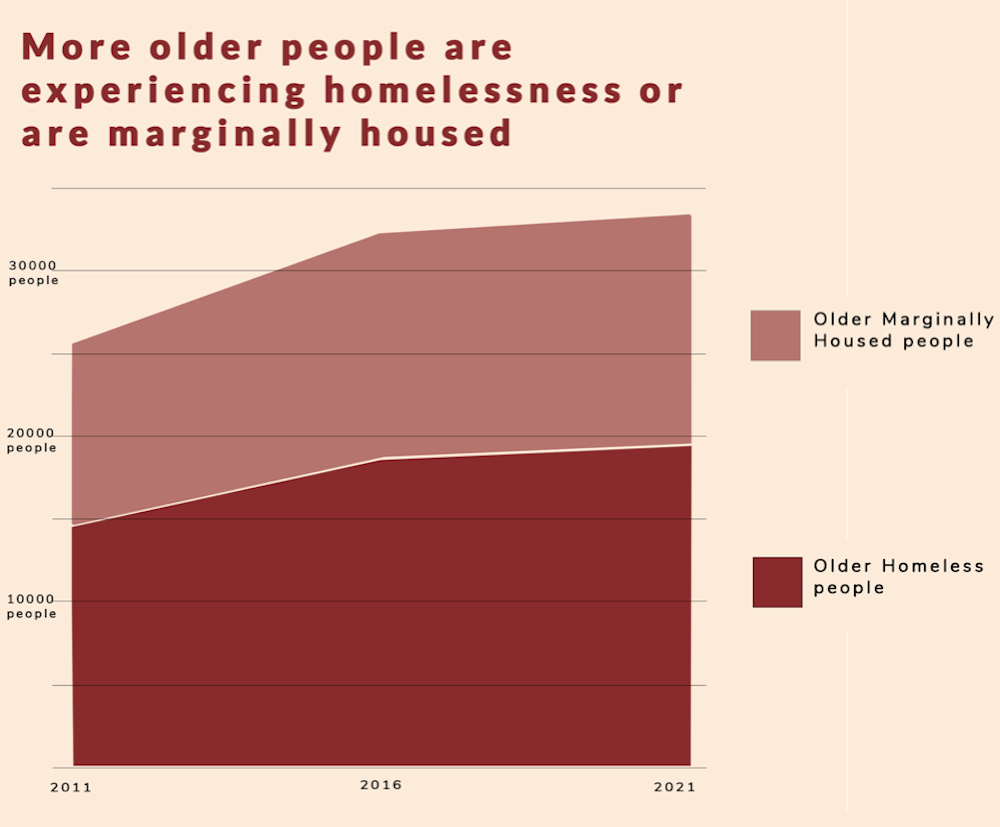

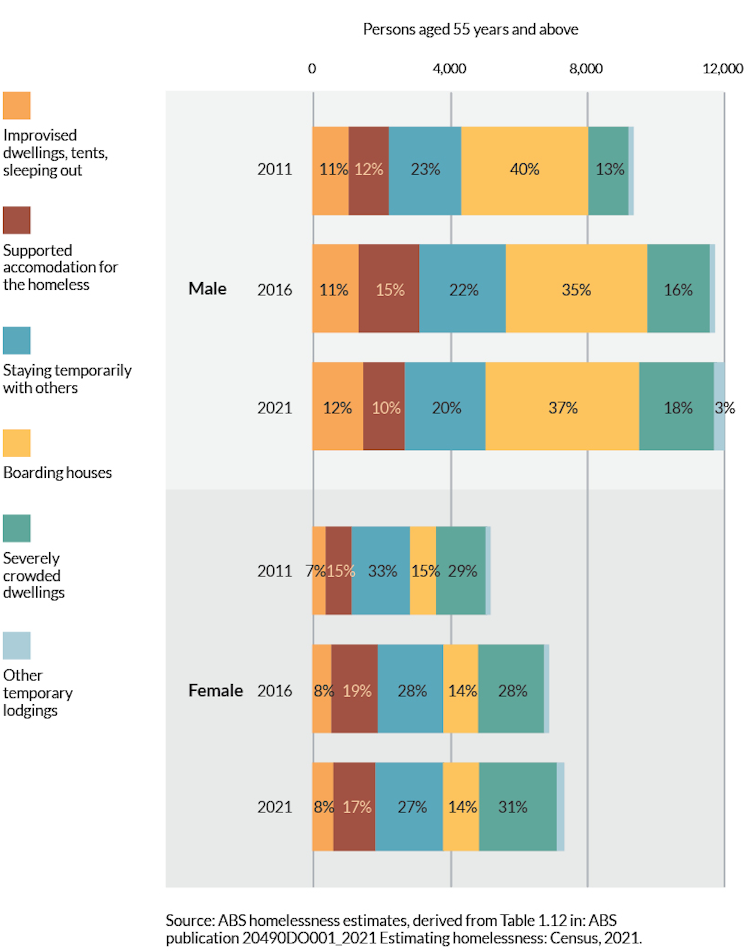

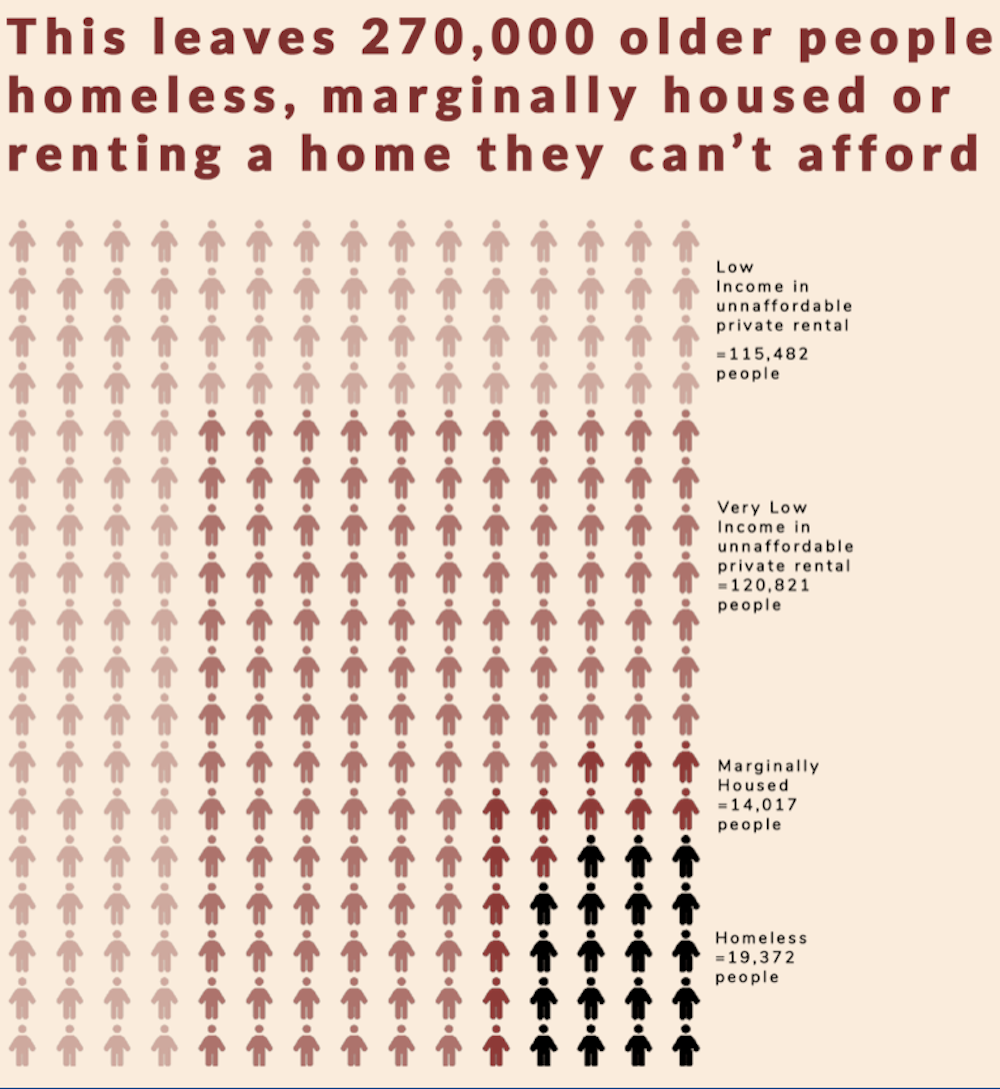

We analysed the most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) census data and homelessness estimates. More older people lived in marginal housing – defined by the ABS as including crowding (less severe), improvised dwellings and caravans – and more were homeless in 2021 than a decade earlier.Older people experiencing homelessness by gender and category in 2011, 2016 and 2021

The proportion of older people in private rental housing has also increased. This means more older people are exposed to the insecurity of renting and rising rents. Our work shows they are struggling to afford private rental housing.

The lowest-income households are the hardest hit. The private rental market is failing to supply housing they can afford. The shortfall in subsidised social housing is huge.

Older people who receive government benefits and allowances are at most risk because their incomes are not keeping up with housing costs.

In 2019-20 only 19% of older people on very low incomes (the lowest 20% of household incomes) lived in households whose rent was affordable. This means four out of five were spending more than 30% of their income on rent (the affordability benchmark for low-income households). Two in five were paying severely unaffordable rents – more than 50% of their income.

Authors & Housing for the Aged Action Group

For older people who don’t own their homes, rising housing prices create financial risk rather than windfall. At the same time, more older people have mortgages. This increases their risk of housing insecurity or financial stress in retirement.

Ageing magnifies unaffordable housing impacts

Rising housing costs, falling home ownership rates, mortgage debt carried into retirement, insecure private rental tenures and the worsening shortage of social housing are markers of system-wide housing insecurity.Insecure or marginal housing affects all generations. However, for older people the risks are made worse by limited income-earning ability, increasing frailty, illness and/or caring responsibilities, growing need for at-home support, and age-based discrimination. These factors make it even harder to meet rising housing costs.

Housing insecurity widens the gap between the housing older people have and the housing they need to live safe, secure and dignified lives as they age.

Authors & Housing for the Aged Action Group

System-wide risks demand system-wide action

Growing housing insecurity among older people is a result of system-wide problems. This means system-wide solutions are needed.We call for:

- adequate social housing supply that reflects population growth and ensures it’s available for older people across all states and territories, including by increasing aged-specific options and reducing the age at which social housing applicants are given priority to 45-55

- stronger national tenancy regulations that prioritise homes over profit

- dedicated marginal and specialist homelessness services that are well designed with and for older people who have experienced housing insecurity and support systems

- support for people to remain in their own homes, across all tenures.

Responses and assistance models must allow for gender diversity, income difference, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people’s cultural needs, as well as those of other culturally and linguistically diverse older people. Disability, caring responsibilities, history of trauma, and individuals’ unique housing pathways and experiences must all be considered.

Older people must have a say in reshaping the housing system. The Albanese government is developing a National Housing and Homelessness Plan. It’s essential that this plan, along with state, territory and local government implementation plans, consider the voices, experiences, concerns and aspirations of older people.

Housing reform is good for everyone

Older people are only one part of the population facing housing insecurity and homelessness. A comprehensive national housing plan must respond to all generational needs. Housing solutions for older people must not come at the expense of – or compete with – the needs of other generations.Housing insecurity and homelessness in childhood, younger years and early adult life all warrant meaningful and urgent housing solutions. Making sure all people have lifelong access to secure housing will begin to reverse the growing problems identified by our report. Otherwise, Australia faces a future where more and more older people struggle with inadequate and unaffordable housing.

National reform that includes a focus on generational needs can deliver a housing system that provides affordable homes for everyone. This will ensure everyone is able to maintain community connections, which for older people means being able to age in safe, secure and affordable homes.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Emma Power, Associate Professor, Geography and Urban Studies, Western Sydney University, Amity James, Associate Professor and Discipline Lead Property, Curtin University, Francesca Perugia, Senior Lecturer, School of Design and the Built Environment, Curtin University, Margaret Reynolds, Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology, Piret Veeroja, Research Fellow, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology, Wendy Stone, Professor of Housing & Social Policy, Centre for Urban Transitions, Swinburne University of Technology