SDC Rewards Member

Upgrade yours now

25-million-year-old fossils of a bizarre possum and strange wombat relative reveal Australia’s hidden past

Relative of Chunia pledgei named Ektopodon serratus (top left), with Wakaleo oldfieldi. Reconstruction

of the early Miocene Kutjumarpu faunal assemblage by Peter Schouten, CC BY-SA

Imagine a vast, lush forest dominated by giant flightless birds and crocodiles. This was Australia’s Red Centre 25 million years ago. There lived several species of koala; early kangaroos the size of possums; and the wombat-sized ancestors of the largest-ever marsupial, Diprotodon optatum (around 2.5 tonnes).

A window onto this ancient time is provided by a little-studied fossil site near Pwerte Marnte Marnte, south of Alice Springs in central Australia. This late Oligocene site yielded the earliest-known fossils of marsupials that look similar to modern ones, as well as fossils from wholly extinct groups such as the enigmatic ilariids, which were something like a koala crossed with a wombat.

While excavating this site from 2014 to 2022, Flinders University palaeontologists have found fossils from many more wonderful animals. In a pair of recently published studies, we name two of these species: a strange wombat relative and an even odder possum.

Flinders University palaeontologists at Pwerte Marnte Marnte fossil site. Arthur Crichton, Author provided

A toothy wombat

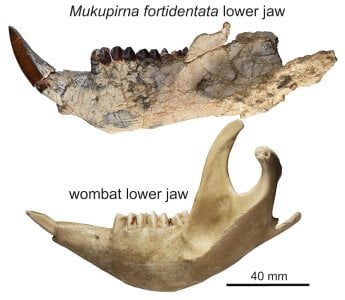

We discovered 35 specimens, including a partial skull and several lower jaws, from an animal that would have looked a bit like a modern wombat crossed with a marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex).Weighing in at around 50kg, it was among the largest marsupials of its time. We named it Mukupirna fortidentata. Everything about its skull and jaws shows this animal had a pretty powerful bite. Its front teeth, for example, were large and spike-shaped, being more like those of squirrels than wombats. These would have enabled them to fracture hard foods, like tough fruits, seeds, nuts and tubers. Its molars, by comparison, were actually quite similar to those of some monkeys, such as macaques.

Left lower jaw of Mukupirna fortidentatacompared with that of the southern hairy-nosed wombat. Arthur Crichton, Author provided

Mukupirna fortidentata is only the second known member of a new family of marsupials described in 2020 called Mukupirnidae. These animals are thought to have diverged from a common ancestor with wombats over 25 million years ago. Sadly, they went extinct shortly thereafter.

Close relative of Mukupirna fortidentata named Mukupirna nambensis. Reconstruction of the Pinpa faunal assemblage by Peter Schouten, CC BY-SA

A nutcracker possum

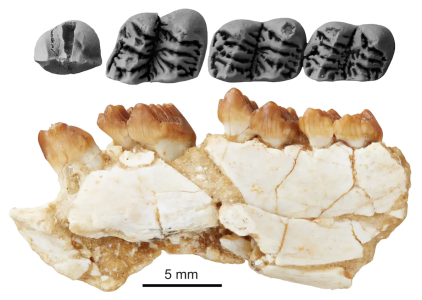

The second species we described is a newly discovered early possum, named Chunia pledgei. It had teeth that would be a dentist’s nightmare, with lots of bladed points (cusps) positioned side by side, like lines on a barcode. This tooth shape is characteristic of species in the poorly known, extinct possum family called Ektopodontidae.The new species is unusual in that it has pyramid-shaped cusps on its front molars. These might have been useful for puncture-crushing hard foods — a bit like a nutcracker.

So what did ektopodontids eat? We don’t really know for sure – there’s no animal like them alive today anywhere in the world. Based on aspects of their molar morphology, we infer they were probably eating fruits and seeds or nuts. But they may have been doing something totally different!

Unfortunately, ektopodontids are tantalisingly rare in the fossil record, known only from isolated teeth and several partial jaws. The fossils show they had a lemur-like short face, with particularly large, forward-facing eyes. But until we find more complete skeletal material, their ecology will likely remain mysterious.

What remains astonishing is just how little we know about the origins of Australia’s living animals, owing in no small part to a 30-million-year gap in the fossil record – half the time between now and the extinction of the dinosaurs.

At the same time, it’s inspiring to think about the countless strange and fascinating animals that must have once lived on this continent. Fossil evidence of these creatures may still be sitting somewhere in the outback, waiting to be discovered.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Arthur Immanuel Crichton, PhD candidate, Flinders University, Aaron Camens, Lecturer in Palaeontology, and Gavin Prideaux, Associate professor, Flinders University