‘Nanoplastics hijack their way through the body’: Experts sound the alarm

By

Maan

- Replies 0

Modern life is filled with unseen risks, some of which are only now coming to light.

What seemed like an abstract environmental concern has turned into a deeply personal issue, with new research uncovering something unexpected inside the human body.

The findings have sparked urgent questions about long-term effects and what this could mean for public health moving forward.

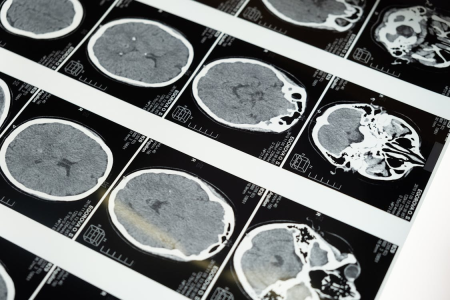

A recent study revealed that human brain samples collected in early 2024 contained significantly more microplastic fragments than those gathered in 2016.

Cadaver brain samples contained significantly higher levels of plastic compared to other organs.

According to co-lead study author and University of New Mexico Regents’ Professor Matthew Campen, the brain had seven to 30 times more plastic than kidney and liver tissues.

‘The concentrations we saw in the brain tissue of normal individuals, who had an average age of about 45 or 50 years old, were 4,800 micrograms per gram, or 0.48 per cent by weight,’ Campen said.

This equated to roughly the same amount of plastic as a standard disposable spoon.

‘Compared to autopsy brain samples from 2016, that’s about 50 per cent higher,’ he said.

‘That would mean that our brains today are 99.5 per cent brain and the rest is plastic.’

While the study indicated a rising presence of plastic in the brain, Campen noted that current methods of measuring microplastics might either overestimate or underestimate their levels.

Further research aimed to refine these measurements in the coming year.

Scientists also detected three to five times more plastic fragments in the brains of individuals diagnosed with dementia before death compared to those without the condition.

These microscopic shards, invisible to the naked eye, were found concentrated in blood vessel walls and immune cells within the brain.

‘It’s a little bit alarming but remember that dementia is a disease where the blood-brain barrier and clearance mechanisms are impaired,’ Campen said.

Inflammatory cells and brain atrophy associated with dementia might create a ‘sink’ for plastic particles to accumulate.

‘We want to be very cautious in interpreting these results as the microplastics are very likely elevated because of (dementia), and we do not currently suggest that microplastics could cause the disease,’ he said.

Plastic deposits were discovered in brain tissue, raising concerns among researchers.

However, Rutgers University pharmacology and toxicology associate professor Phoebe Stapleton stated that their presence did not necessarily indicate harm.

‘It is unclear if, in life, these particles are fluid, entering and leaving the brain, or if they collect in neurological tissues and promote disease,’ she said.

‘Further research is needed to understand how the particles may be interacting with the cells and if this has a toxicological consequence.’

Some evidence suggested that the liver and kidneys could filter certain plastics from the body, but whether the brain had a similar ability remained uncertain.

Microplastics in human tissues have been on the rise, mirroring global environmental trends.

Dr Philip Landrigan, director of the Boston College Program for Global Public Health and the Common Good, linked the rise in microplastics to global environmental changes.

He stated that this increase reflected the surge in plastic production and pollution worldwide.

‘More than half of all plastic ever made has been made since 2002 and production is on track to double by 2040,’ he said.

Landrigan, lead author of a 2023 report by the Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health, stated that plastic exposure affected human health at all stages of its lifecycle.

‘Studies have found these plastics in the human heart, the great blood vessels, the lungs, the liver, the testes, the gastrointestinal tract and the placenta,’ he said.

‘The biggest question is, “OK, what are these particles doing to us?”

‘Honestly there’s a lot we still don’t know.

‘What we do know with real certainty is that these microplastic particles are like Trojan horses—they carry with them all the thousands of chemicals that are in plastics and some of these chemicals are very bad actors.’

Nanoplastics, which are even smaller than microplastics, were especially concerning because they could infiltrate individual cells and disrupt biological processes.

These particles had the potential to introduce harmful endocrine-disrupting chemicals into the body.

Substances such as bisphenols, phthalates, flame retardants, heavy metals, and PFAS were all linked to reproductive issues, infertility, and declining sperm counts.

‘We have some pretty good indications that microplastics and nanoplastics cause harm, even though we are a long way from knowing the full extent of that harm,’ Landrigan said.

‘I would say we have enough information here that we need to start taking protective action.’

The American Chemistry Council stated that existing research did not conclusively show microplastics in food posed health risks.

‘Research underway not only helps address current data gaps in our understanding of exposure to microplastics but it also aims to develop improved tools to measure the toxicity of microplastics to humans,’ the council’s vice president of regulatory and scientific affairs Kimberly Wise White said.

The study was published in Nature Medicine, highlighting a concerning trend.

Researchers examined brain, kidney, and liver samples from forensic autopsies conducted in 2016 and 2024.

They also analysed samples from individuals who died between 1997 and 2013.

Scientists focused on the frontal cortex, a brain region responsible for reasoning and decision-making, which is also heavily affected by dementia-related conditions.

Microplastics ranged from 5mm—about the size of a pencil eraser—to 1 nanometre, with nanoplastics requiring measurement in billionths of a metre.

‘Based on our observations, we think the brain is pulling in the very smallest nanostructures, like 100 to 200 nanometers in length,’ Campen said.

‘These are roughly the size of two COVID viruses side by side.’

These particles could penetrate the blood-brain barrier, potentially by binding to fats that the brain relies on.

‘Somehow these nanoplastics hijack their way through the body and get to the brain, crossing the blood-brain barrier,’ he said.

‘Plastics love fats, or lipids, so one theory is that plastics are hijacking their way with the fats we eat which are then delivered to the organs that really like lipids—the brain is top among those.’

The brain, composed of about 60 per cent fat, depends on dietary sources for essential fatty acids.

While ingestion was the primary way people absorbed microplastics, inhalation also contributed.

‘When people are driving down the highway and their tyres are abrading on the surface of the highway, a certain amount of microplastic particles are thrown into the air,’ Landrigan said.

‘If you live near the coast, some of the microplastic particles that are in the ocean get kicked into the air through wave action,’ he said.

‘So ingestion is probably the dominant route, but inhalation is also an important route.’

Reducing exposure to plastics was possible, even though plastic-free living was unrealistic.

‘It’s important not to scare the hell out of people, because the science in this space is still evolving, and nobody in the year 2025 is going to live without plastic,’ Landrigan said.

‘But do try to minimise your exposure to the plastic that you can avoid, especially single-use plastics.’

Food should be removed from plastic packaging before cooking or microwaving, as heat accelerates plastic leaching.

Reusable fabric bags, metal water bottles, and glass food containers were recommended alternatives.

A 2024 study found a single litre of bottled water contained around 240,000 plastic particles, 90 per cent of which were nanoplastics.

‘Use a metal or glass drinking cup instead of a plastic cup,’ Landrigan said.

‘Store your food in glass containers instead of in plastic ones.’

‘Work in your local community to ban plastic bags, as many communities around the United States have now done.’

‘There is a lot you can do.’

‘And at a societal level, you can join forces with other people who care about children’s health to push for restrictions on plastic manufacture and for the use of safer chemicals in plastics.’

‘Just because we don’t know everything there is to know about every chemical in plastics does not mean we should not take action against the plastic chemicals we know are bad actors.’

With microplastics turning up in nearly every corner of our lives—even our brains—what do you think the long-term impact will be? Are we underestimating the risks, or is the concern overblown?

Share your thoughts in the comments!

What seemed like an abstract environmental concern has turned into a deeply personal issue, with new research uncovering something unexpected inside the human body.

The findings have sparked urgent questions about long-term effects and what this could mean for public health moving forward.

A recent study revealed that human brain samples collected in early 2024 contained significantly more microplastic fragments than those gathered in 2016.

Cadaver brain samples contained significantly higher levels of plastic compared to other organs.

According to co-lead study author and University of New Mexico Regents’ Professor Matthew Campen, the brain had seven to 30 times more plastic than kidney and liver tissues.

‘The concentrations we saw in the brain tissue of normal individuals, who had an average age of about 45 or 50 years old, were 4,800 micrograms per gram, or 0.48 per cent by weight,’ Campen said.

This equated to roughly the same amount of plastic as a standard disposable spoon.

‘Compared to autopsy brain samples from 2016, that’s about 50 per cent higher,’ he said.

‘That would mean that our brains today are 99.5 per cent brain and the rest is plastic.’

While the study indicated a rising presence of plastic in the brain, Campen noted that current methods of measuring microplastics might either overestimate or underestimate their levels.

Further research aimed to refine these measurements in the coming year.

Scientists also detected three to five times more plastic fragments in the brains of individuals diagnosed with dementia before death compared to those without the condition.

These microscopic shards, invisible to the naked eye, were found concentrated in blood vessel walls and immune cells within the brain.

‘It’s a little bit alarming but remember that dementia is a disease where the blood-brain barrier and clearance mechanisms are impaired,’ Campen said.

Inflammatory cells and brain atrophy associated with dementia might create a ‘sink’ for plastic particles to accumulate.

‘We want to be very cautious in interpreting these results as the microplastics are very likely elevated because of (dementia), and we do not currently suggest that microplastics could cause the disease,’ he said.

Plastic deposits were discovered in brain tissue, raising concerns among researchers.

However, Rutgers University pharmacology and toxicology associate professor Phoebe Stapleton stated that their presence did not necessarily indicate harm.

‘It is unclear if, in life, these particles are fluid, entering and leaving the brain, or if they collect in neurological tissues and promote disease,’ she said.

‘Further research is needed to understand how the particles may be interacting with the cells and if this has a toxicological consequence.’

Some evidence suggested that the liver and kidneys could filter certain plastics from the body, but whether the brain had a similar ability remained uncertain.

Microplastics in human tissues have been on the rise, mirroring global environmental trends.

Dr Philip Landrigan, director of the Boston College Program for Global Public Health and the Common Good, linked the rise in microplastics to global environmental changes.

He stated that this increase reflected the surge in plastic production and pollution worldwide.

‘More than half of all plastic ever made has been made since 2002 and production is on track to double by 2040,’ he said.

Landrigan, lead author of a 2023 report by the Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health, stated that plastic exposure affected human health at all stages of its lifecycle.

‘Studies have found these plastics in the human heart, the great blood vessels, the lungs, the liver, the testes, the gastrointestinal tract and the placenta,’ he said.

‘The biggest question is, “OK, what are these particles doing to us?”

‘Honestly there’s a lot we still don’t know.

‘What we do know with real certainty is that these microplastic particles are like Trojan horses—they carry with them all the thousands of chemicals that are in plastics and some of these chemicals are very bad actors.’

Nanoplastics, which are even smaller than microplastics, were especially concerning because they could infiltrate individual cells and disrupt biological processes.

These particles had the potential to introduce harmful endocrine-disrupting chemicals into the body.

Substances such as bisphenols, phthalates, flame retardants, heavy metals, and PFAS were all linked to reproductive issues, infertility, and declining sperm counts.

‘We have some pretty good indications that microplastics and nanoplastics cause harm, even though we are a long way from knowing the full extent of that harm,’ Landrigan said.

‘I would say we have enough information here that we need to start taking protective action.’

The American Chemistry Council stated that existing research did not conclusively show microplastics in food posed health risks.

‘Research underway not only helps address current data gaps in our understanding of exposure to microplastics but it also aims to develop improved tools to measure the toxicity of microplastics to humans,’ the council’s vice president of regulatory and scientific affairs Kimberly Wise White said.

The study was published in Nature Medicine, highlighting a concerning trend.

Researchers examined brain, kidney, and liver samples from forensic autopsies conducted in 2016 and 2024.

They also analysed samples from individuals who died between 1997 and 2013.

Scientists focused on the frontal cortex, a brain region responsible for reasoning and decision-making, which is also heavily affected by dementia-related conditions.

Microplastics ranged from 5mm—about the size of a pencil eraser—to 1 nanometre, with nanoplastics requiring measurement in billionths of a metre.

‘Based on our observations, we think the brain is pulling in the very smallest nanostructures, like 100 to 200 nanometers in length,’ Campen said.

‘These are roughly the size of two COVID viruses side by side.’

These particles could penetrate the blood-brain barrier, potentially by binding to fats that the brain relies on.

‘Somehow these nanoplastics hijack their way through the body and get to the brain, crossing the blood-brain barrier,’ he said.

‘Plastics love fats, or lipids, so one theory is that plastics are hijacking their way with the fats we eat which are then delivered to the organs that really like lipids—the brain is top among those.’

The brain, composed of about 60 per cent fat, depends on dietary sources for essential fatty acids.

While ingestion was the primary way people absorbed microplastics, inhalation also contributed.

‘When people are driving down the highway and their tyres are abrading on the surface of the highway, a certain amount of microplastic particles are thrown into the air,’ Landrigan said.

‘If you live near the coast, some of the microplastic particles that are in the ocean get kicked into the air through wave action,’ he said.

‘So ingestion is probably the dominant route, but inhalation is also an important route.’

Reducing exposure to plastics was possible, even though plastic-free living was unrealistic.

‘It’s important not to scare the hell out of people, because the science in this space is still evolving, and nobody in the year 2025 is going to live without plastic,’ Landrigan said.

‘But do try to minimise your exposure to the plastic that you can avoid, especially single-use plastics.’

Food should be removed from plastic packaging before cooking or microwaving, as heat accelerates plastic leaching.

Reusable fabric bags, metal water bottles, and glass food containers were recommended alternatives.

A 2024 study found a single litre of bottled water contained around 240,000 plastic particles, 90 per cent of which were nanoplastics.

‘Use a metal or glass drinking cup instead of a plastic cup,’ Landrigan said.

‘Store your food in glass containers instead of in plastic ones.’

‘Work in your local community to ban plastic bags, as many communities around the United States have now done.’

‘There is a lot you can do.’

‘And at a societal level, you can join forces with other people who care about children’s health to push for restrictions on plastic manufacture and for the use of safer chemicals in plastics.’

‘Just because we don’t know everything there is to know about every chemical in plastics does not mean we should not take action against the plastic chemicals we know are bad actors.’

Key Takeaways

- Researchers found rising microplastic levels in human brains, with concerns over potential links to dementia and cellular infiltration.

- Microplastics in organs reflect global plastic pollution, carrying harmful chemicals that may disrupt health.

- Experts call for more research but advise reducing plastic exposure through safer alternatives.

- While avoiding plastic entirely is unrealistic, individuals can push for safer materials and stricter regulations.

With microplastics turning up in nearly every corner of our lives—even our brains—what do you think the long-term impact will be? Are we underestimating the risks, or is the concern overblown?

Share your thoughts in the comments!