Australia’s guardians and public trustees are being weaponised under a veil of secrecy

By

ABC News

- Replies 2

For four years, Kayla’s life wasn’t her own.

She couldn’t choose where she lived, what to do with her own money, or who she could talk to.

But now, Kayla has managed to escape the system which controlled her.

She wants to tell her story of how an institution that’s supposed to protect vulnerable people instead turned her into a victim.

But it’s illegal for us to share her real name or face.

Even sharing details about her, such as her hobbies or religious beliefs, is punishable with jail time.

Anyone can apply for the government to take control of someone’s life.

Sometimes applications are made by doctors, carers, or concerned family members.

But they can also be made by complete strangers—and people looking to cause harm.

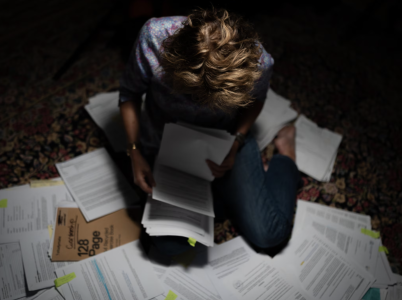

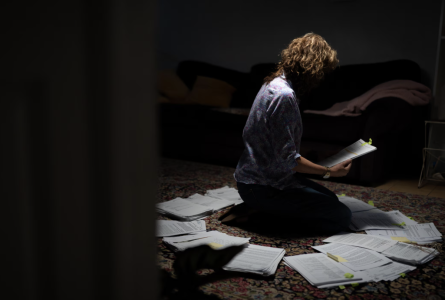

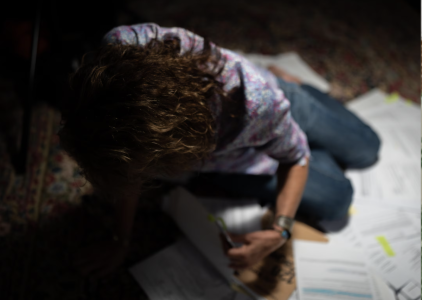

Claire—not her real name—can’t decide whether to cry or laugh at the absurdity of the situation she found herself in.

She’s delving into the paper trail inking a timeline of her daughter’s descent into “hell”.

“Going through the documents, it brings it all back — it brings back the powerlessness that I felt to be able to protect Kayla,” Claire says.

“It’s like a horror story that someone’s made up.”

Kayla was born with a rare brain condition which can cause developmental delays and intellectual disability.

Claire has helped to take care of Kayla’s support needs since she was young, including organising services and medication.

But a messy divorce and one misguided attempt to protect Kayla spiralled everything out of control.

“I had no idea that it would end up with all of Kayla’s rights being stripped off her,” she says.

“Kayla lost total control of her life, and I feel really responsible for that.”

During the asset split with Claire’s former husband, she says she was advised by her lawyer to apply for control of Kayla’s assets through Western Australia’s State Administrative Tribunal (SAT).

“There was $20,000 that belonged to Kayla that I’d saved for her,” Claire says.

“I just wanted to protect her little nest egg.”

Claire’s application was successful, but the fallout of the couple’s bitter separation led them back to the tribunal over, and over again.

“He [former husband] took us back there time, and time, and time again,” Claire says.

The tribunal deemed Kayla incapable of making her own decisions, and put her under the care of the Public Advocate and the Public Trustee.

“I felt completely powerless, I couldn’t protect her anymore,” Claire says.

She felt the state care system was being “weaponised” against her and Kayla.

Descent into despair

First, the state took over decisions about where Kayla could live, and who she could live with.Then, it took over her finances.

Finally, it took away her decisions about the services she could receive, including what support she could have for living with her disability, and legal representation.

“Who the hell are these people? They don’t know anything about my life,” Kayla says, thinking back on her time under state care.

Kayla’s support services, which her mother helped to set up over years, were removed and replaced.

In a statement, the Public Advocate Pauline Bagdonavicius said state guardians’ decisions aim to build a person’s capacity to live as independently as possible.

“Any changes are made in the best interests of the represented person,” she says.

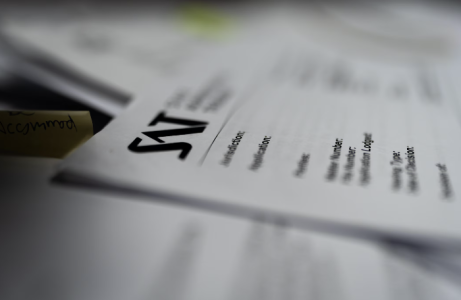

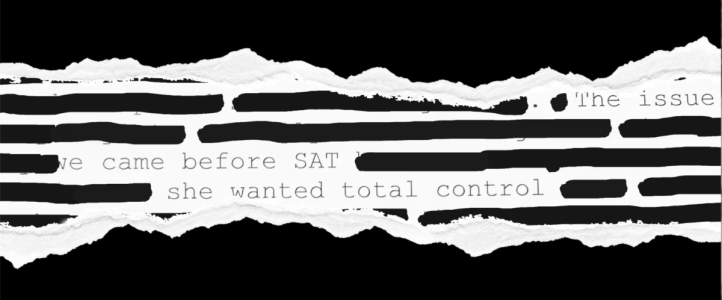

But a past tribunal hearing examining Kayla’s experience heard otherwise.

“That was not in her best interests,” a judge said.

A snippet of a State Administrative Tribunal hearing transcript. Image source: ABC News / Image by: Cason Ho.

The guardian forced Kayla to spend alternating weeks at her father’s house. While there, Kayla would often call her mother.

“She was my security blanket, she was the person that I trusted, she understood my needs,” Kayla says.

“I called her at 4am in tears being like, ‘come get me now, I’m not safe’.”

Kayla alleges her father’s partner threw her phone into a river, and on another occasion yelled and hit her.

“I was woken up many times ... to stuff being thrown, to stuff being broken,” she says.

Kayla’s father denied the allegations in the State Administrative Tribunal, and said Claire was stoking tensions in his house by “actively telling [Kayla] she could do whatever she likes”.

He told the tribunal Claire “wanted total control” over their daughter, that Claire wasn’t a suitable carer, and that he believed it was in his daughter’s best interests if the state controlled her life.

The Public Advocate says state guardians may make decisions about accommodation when there is conflict between parents.

“The delegated guardian is always working to balance views of the represented person and their family members in the best interests of the represented person,” Ms Bagdonavicius says.

Claire repeatedly raised concerns with the guardian about Kayla’s situation, and her vexed relationship with her father’s partner.

“They kept sending her back. They kept saying ‘no, the agreement is that Kayla goes and stays with her father [for] a week and that’s what’s going to happen’,” Claire says.

It was only after Claire took Kayla to a police station to report the alleged abuse incidents that the guardian stopped enforcing the split living arrangement.

By then, Claire’s relationship with Kayla’s guardian had already deteriorated beyond repair.

“I could see Kayla’s wellbeing declining rapidly, I could see things being imposed upon Kayla that I just couldn’t live with,” Claire says.

“I couldn’t get anybody to listen ... and I grew to hate them.”

Kayla’s breath shakes as she recounts trying to tell her state guardian she didn’t feel safe.

“I tried to, but they just dismissed me ... it was very demoralising, it was very upsetting for me,” she says.

“It was like being in a locked box.”

A chance meeting with one woman, who was willing to listen, changed everything.

High stakes

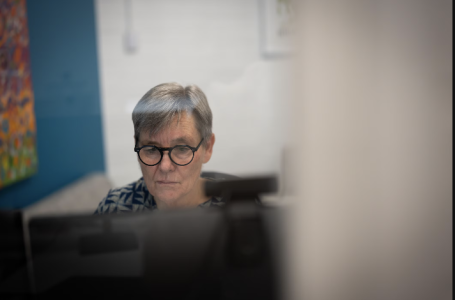

Several organisations which help people in state care have told the ABC they can’t speak publicly out of fear of jeopardising future cases.Maxine Drake is an advocate with Developmental Disability WA who has worked with families through hundreds of tribunal hearings.

Ms Drake hesitates while debating whether to reveal one of her biggest concerns with the system: “I shouldn’t ... yes, maybe I should,” she says.

“People are making applications in a hostile view to try to impinge upon either the freedoms of the person or the freedoms of others around them.”

“[They’re] what might be called ‘vexatious applications’ ... I have absolutely seen circumstances where applications to SAT have been used as a hostile strategy to interfere with families.”

Tribunals are intended to be less formal than a court. There’s no bowing or standing to speak, no formalities like “your honour”, and lawyers aren’t required.

But, the stakes can be just as high.

“I’ve seen people who’ve been voluble, talkative, clear outside the hearing room, and then completely unable to speak in the hearing room,” Ms Drake says.

“There’s very few circumstances where the state can intrude into our lives in this way.”

Life-defining decisions—like the ones made for Kayla about her mental capacity, and who controlled her money or where she lived—can all be made in a tribunal.

“They can be so anxious that they can’t speak straight, and think straight, and act straight, and then that’s how they look like they’re not able to make decisions,” Ms Drake says.

She believes far too many people are unnecessarily having their rights stripped away through the tribunal and state care systems.

“An order can take away a person’s exercise of their own rights—they can, in a sense, encourage a learned helplessness,” she says.

Ms Drake was instrumental in Kayla and her mother Claire’s battle to claw out of state guardianship.

After years of wrestling in the tribunal, the state has relinquished control, and Kayla can now decide for herself where she lives, how she uses her own money, and who she talks to.

“They put me through so much stuff that wasn’t fair ... when I came out of that tribunal hearing and they told me, I screamed,” Kayla says.

“It feels like I’m free.”

Kayla wants to share her story—to show her face, and use her own voice—but it’s illegal to identify her.

Gag order

The guardianship and administration orders put on Kayla are similar to the conservatorship orders which US pop star Britney Spears was under for 13 years, which sparked the #FreeBritney movement.

Fans of Britney Spears began advocating for her conservatorship to be ended several years ago. Image source: ABC News / Image by: Bradley McLennan.

The Free Britney movement has vowed to fight for other Americans who feel unreasonably constrained by their guardianships. Image source: ABC News / Image by: Bradley McLennan.

In Australia, about 50,000 people are under the control of state guardians and public trustees.

Across most of the country, journalists are prohibited from identifying people who are, or have been, under guardianship or administration.

Penalties include fines ranging from $5,000 to $35,000 and imprisonment.

Maxine Drake says the confidentiality provisions are important in some cases, but blanket gag laws prevent the system being held to account.

“The confidentiality laws in this area are a real problem. They’re a problem for the community because there’s no accountability, there’s no visibility in the system,” she says.

“The confidentiality laws, they deny the person themselves from the justice of having their voice heard.”

“Those people should not be gagged — those people are the best people to tell us where things didn’t go right for them, they’re the best ones to reflect on whether there were any benefits in the process for them.”

The ABC contacted the state guardian in every state and territory. Some responded directly, and others through their state governments or departments.

The Australian Capital Territory is the only jurisdiction where people under state guardianship can be identified and details of tribunal proceedings can be reported.

Half the state and territories’ guardians support the removal of blanket gag laws, or in the Northern Territory’s case “sensible reform” that “should carefully consider the ongoing importance of protecting individual privacy”.

In South Australia, people under guardianship can be identified but it’s illegal to report on details of tribunal proceedings.

SA’s guardian said its state’s laws do not stop people from “speaking out about their experiences in the guardianship system more broadly”.

Tasmania’s Department of Justice said “it is more appropriate for confidentiality to be the norm”, and New South Wales and Western Australia did not directly answer the ABC’s questions.

The NSW Government is considering recommendations from its Law Reform Commission and the Disability Royal Commission, and WA’s Law Reform Commission is reviewing its state’s legislation.

WA’s chief law officer, Attorney General Tony Buti—who holds ministerial responsibility over the state tribunal, state guardian and public trustee involved with Kayla’s case—declined an interview.

In response to written questions about the weaponisation of the state care system, gag laws, and scrutiny of the departments responsible for guardianship and administration, a WA Government spokesperson pointed to the ongoing review of the state’s laws.

“The Cook Government is committed to protecting vulnerable people in the community and enhancing the safeguards available for individuals who may be the subject of guardianship or administration arrangements,” the spokesperson said.

“We encourage all Western Australians with an interest in this area to make a submission to the [Law Reform Commission].”

Heartache

It’s been two years since Kayla took her life back into her own hands. She’s since moved out of her mother’s home, has started working, and building her own life.“My daughter’s involvement with guardianship set her back at least two, maybe three years in developing her ability to live independently,” Claire says.

Kayla’s old bedroom has been emptied out and converted into a study—it’s bittersweet for Claire.

“She’s gone ahead in leaps and bounds, she’s now living independently ... in her own place, with supports,” she says.

“I’m so proud of her.”

But the happiness is tinged with the distress and heartache of their years in state care.

“How shocking is it that a department, and people who are supposed to be caring for our most vulnerable people, can damage them in the way that they’ve damaged me and [Kayla],” Claire says.

“All it achieved was to strip her of almost every right that she had as a human being.”

Written by: Cason Ho / ABC News.