Worried your super won’t last? Here’s what the top 5 per cent are doing differently

By

Maan

- Replies 1

Superannuation can feel like a mystery—one that many Aussies spend decades trying to decode.

Beneath the surface of neat averages and tidy projections lies a far more uneven and surprising reality.

What that reveals about your financial future may change how you think about retirement entirely.

Australians have long obsessed over their superannuation, poring over balance sheets and averages in search of reassurance. But those neat little figures don’t tell the full story—far from it.

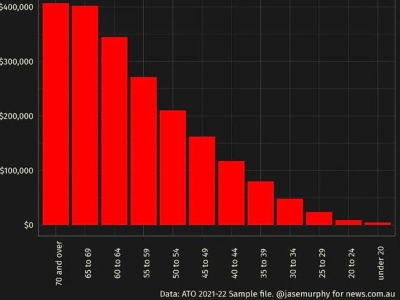

Let’s start with the basics. Charts showing the average super balance by age group are everywhere: under $100,000 for people in their 30s, just over $100,000 for those in their early 40s, a bit more than $200,000 for the early 50s, and upwards of $400,000 for those over 65.

Seems simple, right? Trouble is, these averages give a wildly misleading picture of what most Australians actually hold in super.

‘Superannuation is not like height’, as Jason Murphy pointed out. Averages work fine when we’re talking about traits like that—most people fall close to the middle. But when it comes to wealth, things get lopsided fast. Some Australians have no super at all. Others have millions.

Take the over-60s, for example. That ‘average’ of $400,000? It didn’t reflect the typical person at all. Most people had significantly less. A few had so much more that they dragged the average up by sheer weight of dollars.

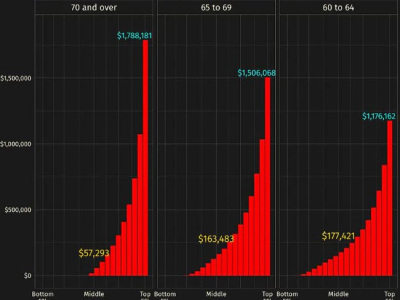

One chart broke this down by grouping 60–64 year olds into 20 segments, each representing 5 per cent of taxpayers. The range was eye-opening. The top 5 per cent held more than $1 million in super—$1.176 million to be exact.

In fact, if you were sitting on a super balance of $177,421 in 2022, you sat squarely at the median for your age group. That meant half of people your age had more than you, and half had less.

And that top 5 per cent? That was only the threshold. Inside that group, it got even more extreme—one Australian reportedly had more than $400 million stashed away in their fund.

This kind of distribution made one thing crystal clear: super is not evenly spread. And while articles often lean on averages to drive a point, they failed to show just how unequal the real landscape was.

That inequality had consequences. For everyday Australians, it fed a sense of anxiety—feeling like they’d fallen behind, like they needed to tip more and more into their super to ‘catch up’.

The superannuation industry wasn’t exactly discouraging this thinking either. The more money people contributed, the more the industry benefited. But was that panic always warranted?

Let’s take a step back.

The pension remained a critical part of retirement income for a large swathe of the population. Despite fears that it might be wound back or scrapped entirely, the data told another story. Far too many Australians were going to need it for it to disappear anytime soon.

In fact, the age pension was indexed to inflation and provided $1,585 a fortnight for couples and $792.50 for singles. If someone owned their home, that wasn’t a bad baseline to work from.

The pension age had already moved from 65 to 67—but that was where it sat for now. No further changes were scheduled.

The idea that super balances alone determined retirement comfort was also flawed. Some people retired with sizeable balances and still saw them grow. If someone’s investments returned $100,000 a year and they only spent $50,000, their super balance rose even after they stopped working.

This dynamic—where lower balances shrank and higher balances continued to grow—was especially visible in post-retirement data.

A combined chart covering people aged 60 to over 70 showed it clearly. For the over-70s, many had run out of super altogether. Their gold-labelled median balance dipped. But the top 5 per cent? Their balances were still on the rise.

Some of that growth could be due to late contributions, but most likely it reflected strong investment performance. Their wealth wasn’t disappearing—it was compounding. And eventually, it would pass on to heirs.

Yet, for those heirs—typically in their 50s and already doing fairly well financially—this inheritance often barely moved the needle.

The super gap was just as stark among younger Australians. In the early 30s, hitting $140,000 (or $133,998 back in 2022) would have landed someone in the top 5 per cent for their age. Few reached that milestone.

Charts covering younger age groups showed that even having $20,000 in super by age 22 placed someone in the top 10 per cent. But the same amount at age 27 only marked the median.

That showed how quickly expectations shifted and how much the system encouraged comparison.

Murphy argued that too much focus on super balances could be distracting. People might worry themselves sick trying to hit some arbitrary number, all while ignoring what they needed right now.

‘Certainly the superannuation industry would like people to put more and more money in their accounts,’ he wrote. ‘They want to create that FOMO feeling!’

But when the numbers were laid out side-by-side across all age groups—from those under 29 to those in their 60s—the truth was impossible to ignore. Most people did not have seven-figure balances. In fact, few even cracked six figures until much later in life.

The pension wasn’t going anywhere. The vast majority of retirees would need it—and get it.

For all the glossy headlines and scary projections, there was a simple truth hiding in plain sight: the numbers we used to measure ourselves against often didn’t mean much at all.

In a previous story, we looked at how Australians across different age groups are tracking with their savings.

It’s a useful snapshot that many seniors found eye-opening.

Take a moment to see where you stand and what others are doing.

With all the talk about super and pensions, how do you reckon Aussies over 60 can make the most of their money now without worrying too much about later? Let us know your thoughts in the comments.

Beneath the surface of neat averages and tidy projections lies a far more uneven and surprising reality.

What that reveals about your financial future may change how you think about retirement entirely.

Australians have long obsessed over their superannuation, poring over balance sheets and averages in search of reassurance. But those neat little figures don’t tell the full story—far from it.

Let’s start with the basics. Charts showing the average super balance by age group are everywhere: under $100,000 for people in their 30s, just over $100,000 for those in their early 40s, a bit more than $200,000 for the early 50s, and upwards of $400,000 for those over 65.

Seems simple, right? Trouble is, these averages give a wildly misleading picture of what most Australians actually hold in super.

‘Superannuation is not like height’, as Jason Murphy pointed out. Averages work fine when we’re talking about traits like that—most people fall close to the middle. But when it comes to wealth, things get lopsided fast. Some Australians have no super at all. Others have millions.

Take the over-60s, for example. That ‘average’ of $400,000? It didn’t reflect the typical person at all. Most people had significantly less. A few had so much more that they dragged the average up by sheer weight of dollars.

One chart broke this down by grouping 60–64 year olds into 20 segments, each representing 5 per cent of taxpayers. The range was eye-opening. The top 5 per cent held more than $1 million in super—$1.176 million to be exact.

In fact, if you were sitting on a super balance of $177,421 in 2022, you sat squarely at the median for your age group. That meant half of people your age had more than you, and half had less.

And that top 5 per cent? That was only the threshold. Inside that group, it got even more extreme—one Australian reportedly had more than $400 million stashed away in their fund.

This kind of distribution made one thing crystal clear: super is not evenly spread. And while articles often lean on averages to drive a point, they failed to show just how unequal the real landscape was.

That inequality had consequences. For everyday Australians, it fed a sense of anxiety—feeling like they’d fallen behind, like they needed to tip more and more into their super to ‘catch up’.

The superannuation industry wasn’t exactly discouraging this thinking either. The more money people contributed, the more the industry benefited. But was that panic always warranted?

Let’s take a step back.

The pension remained a critical part of retirement income for a large swathe of the population. Despite fears that it might be wound back or scrapped entirely, the data told another story. Far too many Australians were going to need it for it to disappear anytime soon.

In fact, the age pension was indexed to inflation and provided $1,585 a fortnight for couples and $792.50 for singles. If someone owned their home, that wasn’t a bad baseline to work from.

The pension age had already moved from 65 to 67—but that was where it sat for now. No further changes were scheduled.

The idea that super balances alone determined retirement comfort was also flawed. Some people retired with sizeable balances and still saw them grow. If someone’s investments returned $100,000 a year and they only spent $50,000, their super balance rose even after they stopped working.

This dynamic—where lower balances shrank and higher balances continued to grow—was especially visible in post-retirement data.

A combined chart covering people aged 60 to over 70 showed it clearly. For the over-70s, many had run out of super altogether. Their gold-labelled median balance dipped. But the top 5 per cent? Their balances were still on the rise.

Some of that growth could be due to late contributions, but most likely it reflected strong investment performance. Their wealth wasn’t disappearing—it was compounding. And eventually, it would pass on to heirs.

Yet, for those heirs—typically in their 50s and already doing fairly well financially—this inheritance often barely moved the needle.

The super gap was just as stark among younger Australians. In the early 30s, hitting $140,000 (or $133,998 back in 2022) would have landed someone in the top 5 per cent for their age. Few reached that milestone.

Charts covering younger age groups showed that even having $20,000 in super by age 22 placed someone in the top 10 per cent. But the same amount at age 27 only marked the median.

That showed how quickly expectations shifted and how much the system encouraged comparison.

Murphy argued that too much focus on super balances could be distracting. People might worry themselves sick trying to hit some arbitrary number, all while ignoring what they needed right now.

‘Certainly the superannuation industry would like people to put more and more money in their accounts,’ he wrote. ‘They want to create that FOMO feeling!’

But when the numbers were laid out side-by-side across all age groups—from those under 29 to those in their 60s—the truth was impossible to ignore. Most people did not have seven-figure balances. In fact, few even cracked six figures until much later in life.

The pension wasn’t going anywhere. The vast majority of retirees would need it—and get it.

For all the glossy headlines and scary projections, there was a simple truth hiding in plain sight: the numbers we used to measure ourselves against often didn’t mean much at all.

In a previous story, we looked at how Australians across different age groups are tracking with their savings.

It’s a useful snapshot that many seniors found eye-opening.

Take a moment to see where you stand and what others are doing.

Key Takeaways

- Superannuation averages are skewed by the wealthiest few and don’t reflect what most Australians actually have.

- The top 5 per cent of over-60s held more than $1 million in super, while the median sat at just $177,421.

- Many retirees rely on the age pension, which remains stable and indexed to inflation, making it a key part of retirement income.

- Focusing too much on super balances creates anxiety, but most people don’t hit six figures until later in life anyway.

With all the talk about super and pensions, how do you reckon Aussies over 60 can make the most of their money now without worrying too much about later? Let us know your thoughts in the comments.

Last edited: