Why is hospital parking so expensive? Two economics researchers explain

- Replies 0

Imagine having to pay A$39 dollars a day to park your car while visiting your sick child in hospital.

For families already struggling in a cost-of-living crisis, hospital parking fees are not just another expense. They can be a financial barrier to supporting loved ones in their most vulnerable moments.

Hospital parking is a big revenue earner. In New South Wales, public hospitals collected almost $51.7 million in parking fees in 2024. That was up from $30.2 million in 2023.

It may be tempting to view hospital parking fees as exploiting a captive market. But the reality is much more complex.

It involves urban economics, pressures on health-care funding and competing demands for limited space, often in busy city centres.

Let's start with supply and demand

Basic economics tells us that price is the mechanism for balancing supply and demand. This is known as the equilibrium price. If demand is greater than supply, the price rises. So for urban hospitals, where parking spaces are limited, this scarcity creates market conditions that, not surprisingly, drive up prices.

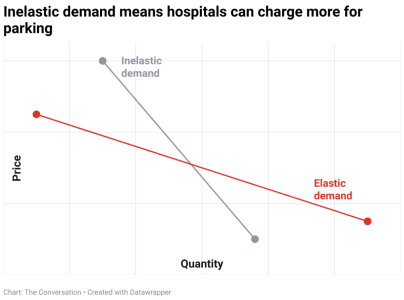

But economics also tells us that if there’s still demand for parking despite the price, then under some circumstances suppliers can charge more than the equilibrium price. Put simply, this “inelastic demand” means it is possible to charge more to a captive audience.

You could certainly argue hospital patients and visitors are a captive audience. While many hospitals are well serviced by public transport, hospital patients and visitors are often too sick or time-poor to use it. So they have little choice than to pay for parking. For rural hospitals, there is limited or no public transport, so visitors have to drive.

So are hospitals taking advantage of the inelastic demand for parking? Are they price gouging – setting prices above what is considered reasonable or fair? Or are there reasons for setting such high prices?

Location, location, location

Car parks of hospitals in prime locations are not just attractive to hospital patients and visitors. They’re also attractive to other users, such as those working in the city or sightseeing. High parking fees deter these users, ensuring spaces are available for hospital users.

High prices prevent hospital users from overstaying. This prevents them doing non-hospital activities (such as shopping) after their hospital appointment or visits and before returning to their cars.

Hospitals also charge high prices to raise revenue for health care. In a statement to the ABC earlier this year, NSW Health said extra money raised from parking is reinvested into health services and facilities.

But it makes sense to encourage visitors

However, raising parking fees to support hospital budgets could be a false economy. We know hospital visitors have an important role in patients’ recovery times. So if high parking costs deter visitors or carers, this could lead to longer hospital stays for their loved ones.

Cheaper parking might allow for more visiting, leading to shorter hospital stays and significant cost savings per patient.

I (Lisa) had firsthand experience of this when my elderly father with dementia was admitted to hospital recently. The hospital allowed 24/7 visitor access for carers (in this case, my mother) and free hospital parking. Access 24/7 is important for patients with dementia who are often disorientated in hospital. This disorientation is typically worse in the evening (known as sundowning).

Having carers present meant staff could focus on medical issues. It facilitated visits outside normal visiting hours (when dementia patients typically need the extra support) and when the demand for parking spaces is lower.

Who needs cheap parking?

High parking prices reflect the high demand for a fixed supply of parking spaces that are rationed to those most willing to pay (those with the income). But a better solution is to ration according to need (that is, to boost patient wellbeing).

The economics solution is to charge different users different prices. Most hospitals do this already by offering concessions. But concessions can differ by hospital or state. Not everyone knows concession-rate parking is available, and it can be hard for some people to find out if they qualify.

So if you are concerned about the cost of hospital parking, know the fees and available concessions before you park. You can find this on most hospitals’ websites.

Currently, concessions are generally based on income (including the possession of a concession card). But we need a greater shift towards providing concession rates based on need. For example those visiting long-stay patients clearly need concessions to support patient wellbeing.

A media campaign has called for a national cap on hospital parking costs for frequent users.

Most car parks have a daily limit but frequent users can soon accumulate large bills over weeks or months of hospital visits. For many patients, particularly those requiring frequent treatments such as dialysis, parking costs accumulate annually.

How could we make things cheaper and fairer?

We need to apply concession rates to hospital visitors on the basis of need, not just income. Need should be informed by patient wellbeing and the importance of visitors to the healing process.

We need a consistent set of rules across hospitals about concession-rate parking. This would simplify the process for hospital car park users.

We also need to look at longer-term solutions. When expanding hospitals or planning new ones, we can consider transitioning away from prime locations. This would help make parking less attractive to non-hospital users.

The challenge for health-care systems is balancing operational necessity of recovering costs with the ethics of equity and access that prevent necessary care.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For families already struggling in a cost-of-living crisis, hospital parking fees are not just another expense. They can be a financial barrier to supporting loved ones in their most vulnerable moments.

Hospital parking is a big revenue earner. In New South Wales, public hospitals collected almost $51.7 million in parking fees in 2024. That was up from $30.2 million in 2023.

It may be tempting to view hospital parking fees as exploiting a captive market. But the reality is much more complex.

It involves urban economics, pressures on health-care funding and competing demands for limited space, often in busy city centres.

Let's start with supply and demand

Basic economics tells us that price is the mechanism for balancing supply and demand. This is known as the equilibrium price. If demand is greater than supply, the price rises. So for urban hospitals, where parking spaces are limited, this scarcity creates market conditions that, not surprisingly, drive up prices.

But economics also tells us that if there’s still demand for parking despite the price, then under some circumstances suppliers can charge more than the equilibrium price. Put simply, this “inelastic demand” means it is possible to charge more to a captive audience.

You could certainly argue hospital patients and visitors are a captive audience. While many hospitals are well serviced by public transport, hospital patients and visitors are often too sick or time-poor to use it. So they have little choice than to pay for parking. For rural hospitals, there is limited or no public transport, so visitors have to drive.

So are hospitals taking advantage of the inelastic demand for parking? Are they price gouging – setting prices above what is considered reasonable or fair? Or are there reasons for setting such high prices?

Location, location, location

Car parks of hospitals in prime locations are not just attractive to hospital patients and visitors. They’re also attractive to other users, such as those working in the city or sightseeing. High parking fees deter these users, ensuring spaces are available for hospital users.

High prices prevent hospital users from overstaying. This prevents them doing non-hospital activities (such as shopping) after their hospital appointment or visits and before returning to their cars.

Hospitals also charge high prices to raise revenue for health care. In a statement to the ABC earlier this year, NSW Health said extra money raised from parking is reinvested into health services and facilities.

Hospitals are often in prime locations, such as Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney’s inner west. Rose Marinelli/Shutterstock

However, raising parking fees to support hospital budgets could be a false economy. We know hospital visitors have an important role in patients’ recovery times. So if high parking costs deter visitors or carers, this could lead to longer hospital stays for their loved ones.

Cheaper parking might allow for more visiting, leading to shorter hospital stays and significant cost savings per patient.

I (Lisa) had firsthand experience of this when my elderly father with dementia was admitted to hospital recently. The hospital allowed 24/7 visitor access for carers (in this case, my mother) and free hospital parking. Access 24/7 is important for patients with dementia who are often disorientated in hospital. This disorientation is typically worse in the evening (known as sundowning).

Having carers present meant staff could focus on medical issues. It facilitated visits outside normal visiting hours (when dementia patients typically need the extra support) and when the demand for parking spaces is lower.

Visitors are great for patients’ wellbeing and help their recovery. So we want to encourage them. DC Studio/Shutterstock

High parking prices reflect the high demand for a fixed supply of parking spaces that are rationed to those most willing to pay (those with the income). But a better solution is to ration according to need (that is, to boost patient wellbeing).

The economics solution is to charge different users different prices. Most hospitals do this already by offering concessions. But concessions can differ by hospital or state. Not everyone knows concession-rate parking is available, and it can be hard for some people to find out if they qualify.

So if you are concerned about the cost of hospital parking, know the fees and available concessions before you park. You can find this on most hospitals’ websites.

Currently, concessions are generally based on income (including the possession of a concession card). But we need a greater shift towards providing concession rates based on need. For example those visiting long-stay patients clearly need concessions to support patient wellbeing.

A media campaign has called for a national cap on hospital parking costs for frequent users.

Most car parks have a daily limit but frequent users can soon accumulate large bills over weeks or months of hospital visits. For many patients, particularly those requiring frequent treatments such as dialysis, parking costs accumulate annually.

How could we make things cheaper and fairer?

We need to apply concession rates to hospital visitors on the basis of need, not just income. Need should be informed by patient wellbeing and the importance of visitors to the healing process.

We need a consistent set of rules across hospitals about concession-rate parking. This would simplify the process for hospital car park users.

We also need to look at longer-term solutions. When expanding hospitals or planning new ones, we can consider transitioning away from prime locations. This would help make parking less attractive to non-hospital users.

The challenge for health-care systems is balancing operational necessity of recovering costs with the ethics of equity and access that prevent necessary care.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.