The financial trick that can stretch your retirement by decades

Noel Whittaker is the author of Wills, Death & Taxes Made Simple and numerous other books on personal finance. Email: [email protected]

For more than half a century, I’ve been extolling the power of compound interest to build wealth. But a recent email suggests the message doesn’t always get through. It read:

‘You’ve long promoted the power of compounding, but frankly, I don’t see the point. If it just means letting bank interest build up—and nearly half gets lost to tax—surely there are better strategies. Am I missing something?’

Let’s start with the maths: the Rule of 72. This simple rule tells you how long it takes for your money to double: divide 72 by your expected rate of return. If I have $100,000 earning 8%, it will double every nine years. But if I leave it in the bank and earn just 3% after tax, it will take 24 years to double. So your rate of return is vital.

The other crucial bit? Time: every time your money doubles, the final double adds more than all the earlier ones put together.

Let’s say you start with $100,000 earning 8%. After nine years, it’s $200,000. After 18 years, $400,000. Then $800,000 after 27 years—and by year 36, it’s grown to $1.6 million.

That’s the magic of compounding.

Now, think about the person who just parks their money in the bank at 3%. It takes 24 years to reach $200,000 and 48 years to reach $400,000. Meanwhile, the long-term investor is sitting on $4 million. These examples highlight just how vital both time and rate of return are.

Let’s dig a little deeper. Compounding simply means reinvesting your earnings instead of spending them.

Take a share portfolio returning 9%—5% from capital growth and 4% from income. The investor who reinvests everything will enjoy the full 9%, meaning their portfolio doubles every eight years. But the one who spends the dividends captures only the 5% growth component, and their money doubles only every 14 years.

But the cream on the cake for anyone investing in growth assets like shares is that capital gains tax isn’t payable until the asset is sold. And if the portfolio leans towards Australian shares—with their franked dividends—there’s virtually no tax on the income either.

That means you’re enjoying the full power of compounding, with no annual erosion from tax.

So, to answer the email: compounding absolutely works, but it would be a mug’s game to leave it sitting in the bank earning a pittance, especially after inflation and taxes have taken their slice.

Here’s a quick case study: Jack and Jill are both 25 and earning $65,000 a year. Each has employer super contributions of 12%.

Jill is money-smart and ensures her super is invested in a high-growth option to maximise returns.

Jack loves betting on the footy and doesn’t think much about super. He leaves his funds in the default investment. As a result, his fund earns just 4% a year.

Fast-forward 40 years: Jill’s super has grown to around $3.3 million; Jack’s is just $1.3 million. These figures were worked out on my Super Contributions Calculator, which is available on my website.

That’s a dramatic example of the power of compounding. Failing to use it cost Jack $2 million. It’s the difference between a comfortable retirement and one spent counting pennies.

Source: YouTube/Finder Australia

And compounding is just as important in retirement as it is while you’re building wealth. Not only does the rate of return determine how much you retire with, it also dictates how long it lasts.

Picture someone who retires at 65 with $1 million in super and plans to draw $60,000 a year, indexed.

If their portfolio earns 8%, the money will last until age 99. But if they play it too safe and earn just 4%, they’ll run out of funds by age 82—and may have to rely entirely on the age pension.

Understanding compounding doesn’t just help with investing, it’s also crucial when borrowing. I’ll explore that in another column soon.

About the author: Noel Whittaker, AM, is the author of Wills, death & taxes made simple and numerous other books on personal finance. An international bestselling author, finance and investment expert, radio broadcaster, newspaper columnist and public speaker, Noel Whittaker is one of the world’s foremost authorities on personal finance. Connect via Twitter or email ([email protected]). You can shop his personal finance books here.

Advice given in this article is general in nature and is not intended to influence readers’ decisions about investing or financial products. Always seek professional advice that takes into account your personal circumstances before making any financial decisions. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author.

For more than half a century, I’ve been extolling the power of compound interest to build wealth. But a recent email suggests the message doesn’t always get through. It read:

‘You’ve long promoted the power of compounding, but frankly, I don’t see the point. If it just means letting bank interest build up—and nearly half gets lost to tax—surely there are better strategies. Am I missing something?’

Let’s start with the maths: the Rule of 72. This simple rule tells you how long it takes for your money to double: divide 72 by your expected rate of return. If I have $100,000 earning 8%, it will double every nine years. But if I leave it in the bank and earn just 3% after tax, it will take 24 years to double. So your rate of return is vital.

The other crucial bit? Time: every time your money doubles, the final double adds more than all the earlier ones put together.

Let’s say you start with $100,000 earning 8%. After nine years, it’s $200,000. After 18 years, $400,000. Then $800,000 after 27 years—and by year 36, it’s grown to $1.6 million.

That’s the magic of compounding.

Now, think about the person who just parks their money in the bank at 3%. It takes 24 years to reach $200,000 and 48 years to reach $400,000. Meanwhile, the long-term investor is sitting on $4 million. These examples highlight just how vital both time and rate of return are.

Let’s dig a little deeper. Compounding simply means reinvesting your earnings instead of spending them.

Take a share portfolio returning 9%—5% from capital growth and 4% from income. The investor who reinvests everything will enjoy the full 9%, meaning their portfolio doubles every eight years. But the one who spends the dividends captures only the 5% growth component, and their money doubles only every 14 years.

But the cream on the cake for anyone investing in growth assets like shares is that capital gains tax isn’t payable until the asset is sold. And if the portfolio leans towards Australian shares—with their franked dividends—there’s virtually no tax on the income either.

That means you’re enjoying the full power of compounding, with no annual erosion from tax.

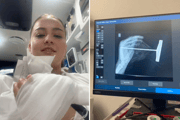

Compounding may give massive advantages for younger people, but can retirees still reap its benefits? Image Credit: Shutterstock

So, to answer the email: compounding absolutely works, but it would be a mug’s game to leave it sitting in the bank earning a pittance, especially after inflation and taxes have taken their slice.

Here’s a quick case study: Jack and Jill are both 25 and earning $65,000 a year. Each has employer super contributions of 12%.

Jill is money-smart and ensures her super is invested in a high-growth option to maximise returns.

Jack loves betting on the footy and doesn’t think much about super. He leaves his funds in the default investment. As a result, his fund earns just 4% a year.

Fast-forward 40 years: Jill’s super has grown to around $3.3 million; Jack’s is just $1.3 million. These figures were worked out on my Super Contributions Calculator, which is available on my website.

That’s a dramatic example of the power of compounding. Failing to use it cost Jack $2 million. It’s the difference between a comfortable retirement and one spent counting pennies.

Source: YouTube/Finder Australia

And compounding is just as important in retirement as it is while you’re building wealth. Not only does the rate of return determine how much you retire with, it also dictates how long it lasts.

Picture someone who retires at 65 with $1 million in super and plans to draw $60,000 a year, indexed.

If their portfolio earns 8%, the money will last until age 99. But if they play it too safe and earn just 4%, they’ll run out of funds by age 82—and may have to rely entirely on the age pension.

Understanding compounding doesn’t just help with investing, it’s also crucial when borrowing. I’ll explore that in another column soon.

About the author: Noel Whittaker, AM, is the author of Wills, death & taxes made simple and numerous other books on personal finance. An international bestselling author, finance and investment expert, radio broadcaster, newspaper columnist and public speaker, Noel Whittaker is one of the world’s foremost authorities on personal finance. Connect via Twitter or email ([email protected]). You can shop his personal finance books here.

Advice given in this article is general in nature and is not intended to influence readers’ decisions about investing or financial products. Always seek professional advice that takes into account your personal circumstances before making any financial decisions. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author.