Sea Change or Sunk Cost? The Real Story of Retiring on a Cruise Ship

By

Maan

- Replies 0

Imagine waking up each morning to a new horizon, the gentle rock of the ocean your constant companion. No lawns to mow, no meals to cook, no beds to make – just endless days of leisure, exploration, and perhaps a cocktail by the pool. For many Australians contemplating their golden years, the idea of retiring permanently on a cruise ship sounds like the ultimate dream, an endless holiday after decades of hard work and home maintenance.

The chatter around this unconventional retirement path is growing louder. It promises escape from the mundane chores of land-based life and offers a seemingly endless vista of new ports and experiences. But as with any dream that sounds too good to be true, it’s worth asking: is this vision of perpetual sunshine and smooth sailing achievable and, more importantly, sustainable? Or are there hidden reefs beneath the sparkling surface?

Recent reports, like one exploring the 'dark side' of this lifestyle, hint that the reality might be more complex. Tales of unexpected costs, daunting health scares, and surprising social challenges suggest that life aboard isn't always smooth sailing. This isn't just about choosing a different type of accommodation; it's about embracing a radically different way of life, one heavily reliant on the ship's ecosystem and far removed from the familiar supports of home. So, let's take a clear-eyed look beyond the glossy brochures and weigh anchor on the real story of retiring at sea.

Then there's the sheer convenience. Life on a cruise ship means outsourcing many of the daily tasks that can become burdensome in later life. Meals are prepared, cabins are cleaned, and laundry services are readily available. The relentless demands of home maintenance – leaky taps, overgrown gardens, cleaning gutters – simply vanish. This freedom from domestic chores is a powerful draw, freeing up time and energy for leisure pursuits.

And leisure is certainly catered for. Cruise ships are floating resorts, packed with amenities and activities. There are swimming pools, gyms, cinemas, libraries, guest lectures, craft classes, nightly shows, and numerous bars and lounges. A built-in entertainment schedule means there's always something happening, offering easy ways to fill the days.

The potential for a vibrant social life is another key attraction. Ships bring together people from diverse backgrounds, offering constant opportunities to meet new faces, share stories over dinner, or join group activities. For some, this constant stream of new connections is invigorating.

There are individuals who have truly made this lifestyle work. Perhaps the most famous is Mario Salcedo, who has lived almost continuously on Royal Caribbean ships for over two decades, earning the moniker 'Super Mario'. He reportedly finds the lifestyle fulfilling and even claims it's cheaper than maintaining a condo in Miami. He works remotely from the ship, managing investment portfolios for a small number of clients, sometimes from a designated 'office' on the pool deck. Having ditched the 'suit-and-tie business world' at age 47 after getting hooked on cruising in 1997, he has fully adapted. 'Cruising never gets old,' Salcedo told All Things Cruise, adding, 'I'm so used to being on ships that it feels more comfortable to me than being on land'.

He admits he's 'lost the land legs,' telling Condé Nast Traveller, 'when I'm swaying so much I can't walk in a straight line'. Despite this, he calls it 'zero stress... The best lifestyle I can find'. His story demonstrates that long-term adaptation is possible, showcasing a life of freedom, social interaction, and unique experiences. However, it's important to remember that his ability to work onboard and his apparent comfort with the very specific social structure might make his case exceptional rather than typical for the average retiree.

The core appeal remains a potent combination of outsourced living and constant novelty, a package deal seemingly tailor-made to counter the potential boredom or burdens of traditional retirement.

The base fare typically covers your cabin, standard meals in main dining rooms and buffets, and basic entertainment.7 What it doesn't usually include is a host of additional, often substantial, costs that can quickly inflate the budget :

The true cost lies not just in the base fare, but in the cumulative impact of these variable and essential add-ons. Unlike the relatively predictable costs of running a paid-off home or the structured fees of a retirement village, cruise ship expenses can fluctuate significantly based on consumption habits, itinerary, and unforeseen needs like medical care. This lack of predictability can be particularly challenging for retirees living on fixed incomes.

Furthermore, the comparison often made between cruise ship costs and nursing home fees can be fundamentally misleading. While the headline figures might seem comparable in some scenarios (e.g., one estimate put basic cruising around $4-5k USD/month vs. $6k USD/month for a US retirement home), they represent vastly different services. Nursing home fees typically include accommodation, meals, and significant levels of personal and medical care.

Cruise fares cover accommodation, basic meals, and transport/entertainment, but provide minimal healthcare within the base price. The high-level care component, often the primary reason for entering a nursing home, is simply not available or included on a cruise ship and would need to be sourced and funded entirely separately, if even possible in that environment.

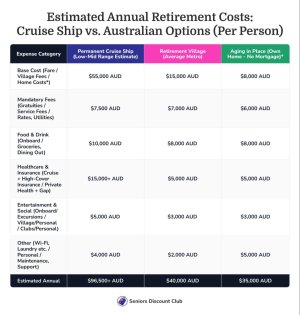

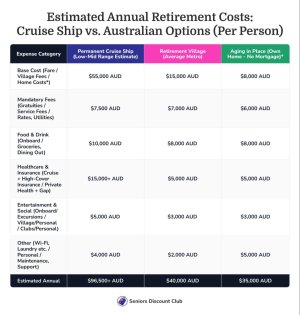

To illustrate the differences, consider this estimated comparison (Note: Figures are indicative estimates based on various sources and will vary significantly based on individual circumstances, choices, location, provider, and currency exchange rates):

This table highlights that while base fares might seem manageable, the total annual cost of cruising, driven largely by essential extras like insurance and potential medical needs, can far exceed typical Australian retirement living expenses. Financial risks also include potential price hikes by cruise lines, itinerary changes impacting costs, or even the remote possibility of a cruise line facing financial difficulty. Careful budgeting and substantial financial reserves are essential.

Most large cruise ships have a small medical centre, typically staffed by one or two doctors and a few nurses. These facilities are equipped to handle common ailments like seasickness, minor injuries, gastrointestinal bugs, and initial stabilisation for more serious emergencies. Think of it more like a well-equipped GP clinic or a small rural urgent care centre, rather than a comprehensive hospital. One passenger compared it favourably to some US emergency rooms for basic care like setting bones or stitches.

Their capabilities have distinct limits. They are not set up for major surgery, complex diagnostic tests (beyond basic X-rays or lab work), specialist consultations, or long-term intensive care. If a passenger suffers a heart attack, stroke, or serious injury, the onboard team's role is to stabilise the patient until they can be evacuated to an appropriate shoreside hospital.

This evacuation process itself presents significant challenges. It depends entirely on the ship's location – being near a major port is vastly different from being mid-ocean. Evacuation can be logistically complex, delayed by weather or distance, and astronomically expensive, potentially running from $20,000 USD to over $100,000 USD, or even hundreds of thousands. This introduces a 'geographic lottery' element to emergency care outcomes, a level of unpredictable risk entirely absent when living near established hospitals in Australia.

Managing chronic conditions also poses difficulties. Accessing specialists for regular check-ups is impossible onboard. Reliably filling complex prescriptions can be problematic, as ship pharmacies mainly stock common or over-the-counter medications. Navigating insurance for large supplies or refilling overseas can be a hurdle. The onboard medical system is fundamentally reactive, designed for acute events, not the proactive, continuous management often required for chronic health issues common in seniors. This mismatch represents a critical vulnerability for permanent residents.

This underscores the absolute necessity of top-tier international health and travel insurance with extremely high coverage limits for medical treatment and, crucially, emergency medical evacuation (recommendations often suggest $100,000 to $1 million USD coverage). Standard Australian private health insurance or Medicare offers little to no coverage outside Australia or in international waters. Policies must be scrutinised for exclusions related to pre-existing conditions, age limits, and specific activities. The high cost of such comprehensive insurance reflects the significant risks involved. Health scares that might be manageable on land can quickly escalate into logistical and financial nightmares at sea.

However, the very nature of cruising presents significant social challenges. The majority of people onboard – both passengers and crew – are transient. Friendships formed one week may dissolve the next as itineraries end and new faces arrive. Building deep, lasting relationships, the kind that provide meaningful support in later life, can be difficult amidst this constant churn. The social environment offers a high quantity of interaction but struggles to deliver consistent quality or depth of connection. This requires a specific personality type – highly adaptable, extroverted, and comfortable with relatively superficial or short-term relationships – to truly thrive.

Despite the crowds, feelings of loneliness and isolation are possible, even common. Permanent residents are a tiny minority. Finding kindred spirits among the ever-changing passenger demographic or the small pool of fellow long-termers isn't guaranteed. Christine Kesteloo, who lives onboard for half the year as the wife of a ship's engineer, has spoken about needing downtime: '...as social as I am... some days I don't want to talk to people, you know I'm so social that my battery just plummets and I just want 24 to 48 hours where I just don't physically talk'.

Furthermore, life on a ship involves relatively confined spaces and a lack of true privacy. While modern cabins are comfortable, they are small compared to land-based homes, often around 200 square feet. Shared public spaces can feel crowded, and escaping for genuine solitude might be difficult. 'Cabin fever' is a real phenomenon. The social dynamic can also be intense, sometimes revolving around activities like heavy drinking or late-night partying that may not appeal to everyone.

Permanent residents occupy a unique social position – neither temporary guest nor working crew member. This 'in-between' status might make it harder to feel fully integrated into the ship's social fabric, potentially requiring deliberate effort to carve out a niche and avoid feeling disconnected from both worlds.

However, balancing these accounts are numerous cautionary tales, often found in online forums and blogs, from those who found the reality didn’t match the dream. Many recount underestimating the true costs, finding the relentless add-ons quickly drained their retirement savings. Others share harrowing stories of health emergencies onboard, highlighting the medical limitations and the terror and expense of needing evacuation far from home, reinforcing the healthcare concerns.

Profound loneliness is another recurring theme in negative accounts, with individuals finding it impossible to form meaningful connections amidst the transient passenger flow, ultimately feeling more isolated surrounded by people than they might have felt alone on land.

Christine Kesteloo’s balanced perspective acknowledges both the joys of travel and the challenges. While she loves not having to cook or do laundry, she also admits the constant availability of food is a major challenge: 'One of the hardest things about living on a cruise ship is that I know right now, if I just leave my cabin, I can go and have cookies, pizza, a shake... The hardest part is telling myself not to eat.' The feeling of being 'stuck' or suffering from 'cabin fever' due to the confined environment and lack of personal space is also frequently mentioned.

Canadian couple Tori Carter and Kirk Rickman, who sold their house to cruise full-time, enjoy the lifestyle but acknowledge the need for careful budgeting and planning, sometimes needing flights to connect different cruise itineraries. They also prefer the flexibility of moving between ships rather than committing to a single residential vessel, partly due to potential issues like noisy neighbours.

These contrasting experiences underscore that success in permanent cruising appears highly dependent on individual factors: financial resilience, robust health, a specific outgoing and adaptable personality, realistic expectations, and a high tolerance for instability. What works wonderfully for one person might be untenable for another. The lifestyle also demands flexibility beyond just daily routines; adjusting to new ships during dry docks, changing itineraries, and potential disruptions are part of the package, requiring an ability to navigate transitions smoothly.

Weighing these options involves looking at key factors:

However, as we've explored, this dream comes with significant potential drawbacks, particularly for older Australians. The costs can be substantially higher and far less predictable than initial estimates suggest, driven by essential extras like comprehensive insurance and onboard spending. The healthcare situation presents perhaps the most serious hurdle: onboard facilities are limited, managing chronic conditions is difficult, and emergencies in remote locations pose significant logistical, financial, and health risks. Socially, the constant churn of passengers can make deep connections elusive, potentially leading to loneliness despite the crowds. The lack of personal space and autonomy within the confines of a ship also needs careful consideration.

Therefore, contemplating this life change requires rigorous and honest self-assessment:

While permanent cruising might be a viable and joyful reality for a select few – typically those who are exceptionally healthy, financially secure, highly adaptable, and perhaps still working remotely like Mario Salcedo – it's unlikely to be a suitable or sustainable option for the majority of older Australians. The significant risks and potential downsides, particularly concerning health security and cost predictability, appear to outweigh the benefits when compared to more conventional retirement paths like villages or aging in place with appropriate support. Even newer residential ship models, while potentially offering more luxury or a slightly more stable community, likely face the same fundamental challenges related to healthcare access far from port and the inherent transience of life at sea.

Before making any decisions, thorough personal research is crucial. Consider trying several extended cruises (a month or longer) on different lines to get a realistic feel for the lifestyle. Consult with independent financial advisors and discuss the implications frankly with family. Retiring on a cruise ship is a life-altering choice, and while the horizon looks appealing, it’s vital to know the depth of the waters before setting sail permanently.

For those considering permanent cruising, the lifestyle may seem like a dream, but it's not without its challenges. Do you think the perks of constant travel outweigh the risks? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

The chatter around this unconventional retirement path is growing louder. It promises escape from the mundane chores of land-based life and offers a seemingly endless vista of new ports and experiences. But as with any dream that sounds too good to be true, it’s worth asking: is this vision of perpetual sunshine and smooth sailing achievable and, more importantly, sustainable? Or are there hidden reefs beneath the sparkling surface?

Recent reports, like one exploring the 'dark side' of this lifestyle, hint that the reality might be more complex. Tales of unexpected costs, daunting health scares, and surprising social challenges suggest that life aboard isn't always smooth sailing. This isn't just about choosing a different type of accommodation; it's about embracing a radically different way of life, one heavily reliant on the ship's ecosystem and far removed from the familiar supports of home. So, let's take a clear-eyed look beyond the glossy brochures and weigh anchor on the real story of retiring at sea.

What's the Appeal? Sunshine, Buffets, and No More Mowing!

The allure of permanent cruising is undeniable, tapping directly into common retirement aspirations for travel, leisure, and freedom from responsibility, amplified to an extraordinary degree. First and foremost is the promise of constant travel without the usual hassles. Imagine exploring the Mediterranean one month, the Caribbean the next, all without ever packing or unpacking a suitcase beyond your initial move-in. Waking up to different scenery, from bustling port cities to tranquil tropical islands, offers a level of stimulation and novelty hard to match on land.Then there's the sheer convenience. Life on a cruise ship means outsourcing many of the daily tasks that can become burdensome in later life. Meals are prepared, cabins are cleaned, and laundry services are readily available. The relentless demands of home maintenance – leaky taps, overgrown gardens, cleaning gutters – simply vanish. This freedom from domestic chores is a powerful draw, freeing up time and energy for leisure pursuits.

And leisure is certainly catered for. Cruise ships are floating resorts, packed with amenities and activities. There are swimming pools, gyms, cinemas, libraries, guest lectures, craft classes, nightly shows, and numerous bars and lounges. A built-in entertainment schedule means there's always something happening, offering easy ways to fill the days.

The potential for a vibrant social life is another key attraction. Ships bring together people from diverse backgrounds, offering constant opportunities to meet new faces, share stories over dinner, or join group activities. For some, this constant stream of new connections is invigorating.

There are individuals who have truly made this lifestyle work. Perhaps the most famous is Mario Salcedo, who has lived almost continuously on Royal Caribbean ships for over two decades, earning the moniker 'Super Mario'. He reportedly finds the lifestyle fulfilling and even claims it's cheaper than maintaining a condo in Miami. He works remotely from the ship, managing investment portfolios for a small number of clients, sometimes from a designated 'office' on the pool deck. Having ditched the 'suit-and-tie business world' at age 47 after getting hooked on cruising in 1997, he has fully adapted. 'Cruising never gets old,' Salcedo told All Things Cruise, adding, 'I'm so used to being on ships that it feels more comfortable to me than being on land'.

He admits he's 'lost the land legs,' telling Condé Nast Traveller, 'when I'm swaying so much I can't walk in a straight line'. Despite this, he calls it 'zero stress... The best lifestyle I can find'. His story demonstrates that long-term adaptation is possible, showcasing a life of freedom, social interaction, and unique experiences. However, it's important to remember that his ability to work onboard and his apparent comfort with the very specific social structure might make his case exceptional rather than typical for the average retiree.

The core appeal remains a potent combination of outsourced living and constant novelty, a package deal seemingly tailor-made to counter the potential boredom or burdens of traditional retirement.

Don't Sink the Budget: Counting the Cost of Cruising

While the dream is enticing, the financial reality requires careful navigation. The idea that living on a cruise ship can be cheaper than land-based options, particularly nursing homes or retirement villages, often surfaces. Estimates might suggest annual costs starting from $50,000-$60,000 AUD per person for basic fares on mainstream lines, with some experienced cruisers managing daily costs around $80-$100 USD per person for inside or balcony cabins through careful planning. However, this figure is often just the tip of the iceberg.The base fare typically covers your cabin, standard meals in main dining rooms and buffets, and basic entertainment.7 What it doesn't usually include is a host of additional, often substantial, costs that can quickly inflate the budget :

- Mandatory Gratuities/Service Charges: Most lines automatically add a daily charge per person (often $20-$30 AUD or around $12-$15 USD) for crew tips. Over a year, this alone adds thousands.

- Onboard Expenses: Fancy a barista coffee, a glass of wine with dinner, or a meal in a specialty restaurant? These cost extra. Drinks packages can mitigate this, but they come at a price. Wi-Fi access is often notoriously slow and expensive. Laundry services, unless you have access to self-serve machines (not always available), add up.

- Shore Excursions: Visiting those exotic ports usually involves paying for tours or transport if you want to explore beyond the immediate dock area.

- Medical Costs: Consultations with the ship's doctor or nurse are charged privately, often at rates significantly higher than a GP visit covered by Medicare. Any treatments or medications administered onboard also come at a cost.

- Insurance: This is non-negotiable and potentially one of the largest ancillary costs.7 Standard travel insurance is insufficient. Permanent cruisers need comprehensive, long-term international health insurance with very high coverage limits, specifically including emergency medical evacuation from anywhere in the world. For seniors, especially those with pre-existing conditions, premiums can skyrocket, potentially costing thousands annually. One analysis found travellers over 70 paid 3.5 times more than those in their 60s, even before covering existing conditions.

- Other Costs: Don't forget visas for certain countries, international phone plans, potential flights home for family emergencies or specific appointments, and personal shopping.

The true cost lies not just in the base fare, but in the cumulative impact of these variable and essential add-ons. Unlike the relatively predictable costs of running a paid-off home or the structured fees of a retirement village, cruise ship expenses can fluctuate significantly based on consumption habits, itinerary, and unforeseen needs like medical care. This lack of predictability can be particularly challenging for retirees living on fixed incomes.

Furthermore, the comparison often made between cruise ship costs and nursing home fees can be fundamentally misleading. While the headline figures might seem comparable in some scenarios (e.g., one estimate put basic cruising around $4-5k USD/month vs. $6k USD/month for a US retirement home), they represent vastly different services. Nursing home fees typically include accommodation, meals, and significant levels of personal and medical care.

Cruise fares cover accommodation, basic meals, and transport/entertainment, but provide minimal healthcare within the base price. The high-level care component, often the primary reason for entering a nursing home, is simply not available or included on a cruise ship and would need to be sourced and funded entirely separately, if even possible in that environment.

To illustrate the differences, consider this estimated comparison (Note: Figures are indicative estimates based on various sources and will vary significantly based on individual circumstances, choices, location, provider, and currency exchange rates):

*Assumptions: Home owned outright for Aging in Place. Cruise estimate based on inside cabin, mainstream line, moderate onboard spending, and assumes high-cost comprehensive insurance Retirement Village includes average recurrent charges, excludes entry/exit fees. Figures derived from various sources and converted/adjusted for illustrative comparison.

This table highlights that while base fares might seem manageable, the total annual cost of cruising, driven largely by essential extras like insurance and potential medical needs, can far exceed typical Australian retirement living expenses. Financial risks also include potential price hikes by cruise lines, itinerary changes impacting costs, or even the remote possibility of a cruise line facing financial difficulty. Careful budgeting and substantial financial reserves are essential.

SOS? Health and Healthcare on the High Seas

Beyond the budget, perhaps the most critical consideration for older Australians contemplating permanent cruising is healthcare. While cruise ships project an image of carefree fun, the reality of medical support onboard is limited and primarily designed for a transient, generally healthy population, not the complex, ongoing needs often associated with aging.Most large cruise ships have a small medical centre, typically staffed by one or two doctors and a few nurses. These facilities are equipped to handle common ailments like seasickness, minor injuries, gastrointestinal bugs, and initial stabilisation for more serious emergencies. Think of it more like a well-equipped GP clinic or a small rural urgent care centre, rather than a comprehensive hospital. One passenger compared it favourably to some US emergency rooms for basic care like setting bones or stitches.

Their capabilities have distinct limits. They are not set up for major surgery, complex diagnostic tests (beyond basic X-rays or lab work), specialist consultations, or long-term intensive care. If a passenger suffers a heart attack, stroke, or serious injury, the onboard team's role is to stabilise the patient until they can be evacuated to an appropriate shoreside hospital.

This evacuation process itself presents significant challenges. It depends entirely on the ship's location – being near a major port is vastly different from being mid-ocean. Evacuation can be logistically complex, delayed by weather or distance, and astronomically expensive, potentially running from $20,000 USD to over $100,000 USD, or even hundreds of thousands. This introduces a 'geographic lottery' element to emergency care outcomes, a level of unpredictable risk entirely absent when living near established hospitals in Australia.

Managing chronic conditions also poses difficulties. Accessing specialists for regular check-ups is impossible onboard. Reliably filling complex prescriptions can be problematic, as ship pharmacies mainly stock common or over-the-counter medications. Navigating insurance for large supplies or refilling overseas can be a hurdle. The onboard medical system is fundamentally reactive, designed for acute events, not the proactive, continuous management often required for chronic health issues common in seniors. This mismatch represents a critical vulnerability for permanent residents.

This underscores the absolute necessity of top-tier international health and travel insurance with extremely high coverage limits for medical treatment and, crucially, emergency medical evacuation (recommendations often suggest $100,000 to $1 million USD coverage). Standard Australian private health insurance or Medicare offers little to no coverage outside Australia or in international waters. Policies must be scrutinised for exclusions related to pre-existing conditions, age limits, and specific activities. The high cost of such comprehensive insurance reflects the significant risks involved. Health scares that might be manageable on land can quickly escalate into logistical and financial nightmares at sea.

Shipmates or Stranded? The Social Life at Sea

Being surrounded by thousands of people on a cruise ship might seem like a guarantee against loneliness, but the social reality for permanent residents is more complex. On one hand, there are constant opportunities for interaction: striking up conversations at the buffet, joining trivia teams, attending shows, or meeting fellow passengers on shore excursions. For outgoing individuals, this can be a stimulating environment. A small number of long-term residents may also form their own sense of camaraderie.However, the very nature of cruising presents significant social challenges. The majority of people onboard – both passengers and crew – are transient. Friendships formed one week may dissolve the next as itineraries end and new faces arrive. Building deep, lasting relationships, the kind that provide meaningful support in later life, can be difficult amidst this constant churn. The social environment offers a high quantity of interaction but struggles to deliver consistent quality or depth of connection. This requires a specific personality type – highly adaptable, extroverted, and comfortable with relatively superficial or short-term relationships – to truly thrive.

Despite the crowds, feelings of loneliness and isolation are possible, even common. Permanent residents are a tiny minority. Finding kindred spirits among the ever-changing passenger demographic or the small pool of fellow long-termers isn't guaranteed. Christine Kesteloo, who lives onboard for half the year as the wife of a ship's engineer, has spoken about needing downtime: '...as social as I am... some days I don't want to talk to people, you know I'm so social that my battery just plummets and I just want 24 to 48 hours where I just don't physically talk'.

Furthermore, life on a ship involves relatively confined spaces and a lack of true privacy. While modern cabins are comfortable, they are small compared to land-based homes, often around 200 square feet. Shared public spaces can feel crowded, and escaping for genuine solitude might be difficult. 'Cabin fever' is a real phenomenon. The social dynamic can also be intense, sometimes revolving around activities like heavy drinking or late-night partying that may not appeal to everyone.

Permanent residents occupy a unique social position – neither temporary guest nor working crew member. This 'in-between' status might make it harder to feel fully integrated into the ship's social fabric, potentially requiring deliberate effort to carve out a niche and avoid feeling disconnected from both worlds.

Real Stories from the Lido Deck: Voices of Experience

Beyond the statistics and logistics, the lived experiences of those who have tried permanent cruising offer valuable perspectives. The narrative is often dominated by outliers like Mario Salcedo, who genuinely loves the lifestyle, feels 'more comfortable to me than being on land,' and has successfully integrated his work and life onboard for decades. His positive experience, echoed by others who relish the freedom from chores, constant travel, and service, shows it can be a dream come true for some.However, balancing these accounts are numerous cautionary tales, often found in online forums and blogs, from those who found the reality didn’t match the dream. Many recount underestimating the true costs, finding the relentless add-ons quickly drained their retirement savings. Others share harrowing stories of health emergencies onboard, highlighting the medical limitations and the terror and expense of needing evacuation far from home, reinforcing the healthcare concerns.

Profound loneliness is another recurring theme in negative accounts, with individuals finding it impossible to form meaningful connections amidst the transient passenger flow, ultimately feeling more isolated surrounded by people than they might have felt alone on land.

Christine Kesteloo’s balanced perspective acknowledges both the joys of travel and the challenges. While she loves not having to cook or do laundry, she also admits the constant availability of food is a major challenge: 'One of the hardest things about living on a cruise ship is that I know right now, if I just leave my cabin, I can go and have cookies, pizza, a shake... The hardest part is telling myself not to eat.' The feeling of being 'stuck' or suffering from 'cabin fever' due to the confined environment and lack of personal space is also frequently mentioned.

Canadian couple Tori Carter and Kirk Rickman, who sold their house to cruise full-time, enjoy the lifestyle but acknowledge the need for careful budgeting and planning, sometimes needing flights to connect different cruise itineraries. They also prefer the flexibility of moving between ships rather than committing to a single residential vessel, partly due to potential issues like noisy neighbours.

These contrasting experiences underscore that success in permanent cruising appears highly dependent on individual factors: financial resilience, robust health, a specific outgoing and adaptable personality, realistic expectations, and a high tolerance for instability. What works wonderfully for one person might be untenable for another. The lifestyle also demands flexibility beyond just daily routines; adjusting to new ships during dry docks, changing itineraries, and potential disruptions are part of the package, requiring an ability to navigate transitions smoothly.

Cruise Ship vs. Cul-de-Sac: How Does it Stack Up?

When considering permanent cruising, it's essential to compare it directly with more conventional Australian retirement options.- Retirement Villages: These offer a sense of community, security, facilities tailored to seniors, and sometimes graded levels of healthcare support or priority access to adjacent care facilities. Compared to cruising, they provide stability, deeper community roots, and more predictable costs (though entry and exit fees can be complex and substantial). The trade-offs are typically less travel, potentially restrictive rules, and a potential feeling of lost independence for some. The cost structure, while involving potentially large buy-ins and exit fees, generally results in lower ongoing annual expenses compared to full-time cruising.

- Aging in Place (Staying Home): For those who own their home, this offers familiarity, independence, connection to existing social networks, and potentially the lowest ongoing cost. The downsides include the burden of home maintenance, the potential for isolation if mobility decreases or support networks weaken, and the need to proactively arrange and pay for any necessary support services (cleaning, gardening, personal care). It offers maximum autonomy and familiarity but lacks the built-in services and social structure of a cruise ship or village.

Weighing these options involves looking at key factors:

- Cost: Cruising involves high and variable costs, particularly due to insurance and extras. Villages have structured fees, often involving substantial entry and exit costs but lower recurrent charges. Aging in place can be the cheapest if the home is owned, but it requires budgeting for maintenance and potential support services. Predictability favours land-based options.

- Healthcare: Cruising offers limited onboard care and significant risks and costs related to emergencies far from comprehensive facilities. It's unsuitable for complex chronic conditions. Villages may offer some onsite support or easier access to local services. Aging in place relies on accessing community healthcare, which is generally comprehensive in Australia but requires individual effort to coordinate.

- Community: Cruising offers constant novelty but transient connections. Villages provide a stable, age-specific community but can feel insular. Aging in place relies on existing networks, which can be strong but may diminish over time. The type of social connection desired is key.

- Independence & Control: Cruising offers freedom from chores but limits freedom of movement and personal space/choice, as it is bound by the ship's rules and itinerary. Aging in place offers maximum personal autonomy but includes the responsibility of self-management. Villages offer a middle ground, with services provided but also rules and community expectations.

- Lifestyle: Cruising prioritises travel, novelty, and service. Land-based options prioritise stability, familiarity, and deeper community ties.

Charting Your Course: Is Retiring at Sea Right for You?

The dream of an endless cruise is powerful, offering unparalleled travel opportunities and the ultimate convenience. Waking up to a new view every few days, with meals prepared and cabins cleaned, holds undeniable appeal for those seeking adventure and freedom from domestic responsibilities in retirement.However, as we've explored, this dream comes with significant potential drawbacks, particularly for older Australians. The costs can be substantially higher and far less predictable than initial estimates suggest, driven by essential extras like comprehensive insurance and onboard spending. The healthcare situation presents perhaps the most serious hurdle: onboard facilities are limited, managing chronic conditions is difficult, and emergencies in remote locations pose significant logistical, financial, and health risks. Socially, the constant churn of passengers can make deep connections elusive, potentially leading to loneliness despite the crowds. The lack of personal space and autonomy within the confines of a ship also needs careful consideration.

Therefore, contemplating this life change requires rigorous and honest self-assessment:

- Finances: Are you prepared for annual costs potentially exceeding $100,000 AUD per person, with significant variability and the need for substantial contingency funds? Can you secure and afford top-tier international health insurance with high evacuation cover, potentially costing thousands per year, especially with age or pre-existing conditions?

- Health: Are you currently in excellent health with no major chronic conditions requiring regular specialist care or complex medication management? Are you prepared for the risks associated with limited medical facilities and potential evacuation delays and costs?

- Personality: Are you highly adaptable, outgoing, and comfortable forming relatively transient relationships? Can you tolerate crowds, limited personal space, and adherence to the ship's schedule and rules? Can you handle potential social isolation or the need for deliberate social effort?

- Risk Tolerance: Are you comfortable with a higher degree of uncertainty regarding costs, healthcare access, and social stability compared to traditional retirement options? This lifestyle is less a predictable plan and more an ongoing adventure with inherent hazards.

While permanent cruising might be a viable and joyful reality for a select few – typically those who are exceptionally healthy, financially secure, highly adaptable, and perhaps still working remotely like Mario Salcedo – it's unlikely to be a suitable or sustainable option for the majority of older Australians. The significant risks and potential downsides, particularly concerning health security and cost predictability, appear to outweigh the benefits when compared to more conventional retirement paths like villages or aging in place with appropriate support. Even newer residential ship models, while potentially offering more luxury or a slightly more stable community, likely face the same fundamental challenges related to healthcare access far from port and the inherent transience of life at sea.

Before making any decisions, thorough personal research is crucial. Consider trying several extended cruises (a month or longer) on different lines to get a realistic feel for the lifestyle. Consult with independent financial advisors and discuss the implications frankly with family. Retiring on a cruise ship is a life-altering choice, and while the horizon looks appealing, it’s vital to know the depth of the waters before setting sail permanently.

Key Takeaways

- ]

- Living on a cruise ship as a permanent retirement option offers freedom from home maintenance but comes with hidden costs like insurance, medical care, and variable expenses.

- Health support on cruise ships is limited, with serious emergencies requiring evacuation, which can be costly and complicated

- Permanent cruising offers constant travel and convenience but comes with unpredictable costs and healthcare challenges.

- Success depends on health, finances, personality, and risk tolerance, making it unsuitable for many older Australians.

For those considering permanent cruising, the lifestyle may seem like a dream, but it's not without its challenges. Do you think the perks of constant travel outweigh the risks? Share your thoughts in the comments below.