Range anxiety–or charger drama? Australians are buying hybrid cars because they don’t trust public chargers

- Replies 0

Range anxiety has long been seen as the main obstacle stopping drivers from going electric.

But range isn’t the real issue. The average range of a new electric vehicle (EV) is more than 450 kilometres, and top models offer more than 700km per charge. By contrast, the average car is driven about 33km per day in Australia as of 2020.

What’s really going on is charger anxiety – the question of whether you can find somewhere reliable to recharge when you’re away from home. Australia’s public chargers are not common enough or reliable enough to give motorists certainty they can find a place to recharge.

This is why many drivers are hedging their bets. Rather than embracing battery-electric vehicles, many Australian drivers are opting for hybrids as well as plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), which couple a smaller battery with an internal combustion engine. Hybrids and PHEVs accounted for almost 20% of new car sales from July–September last year, compared to 6.5% for fully electric vehicles.

Labor’s reelection could lead to better charging infrastructure. Last term, the federal government set a goal of a fast charging station every 150km along major highways, while state governments are also building more. But so far, these efforts aren’t enough to ensure Australia has reliable chargers in the right locations. Until then, cautious drivers will buy hybrids.

Public chargers matter

EV owners charge their cars at home an estimated 70–85% of the time. They use public chargers just 10–20% of the time and workplace charging 6–10% of the time.

This makes sense – home charging is reliable and cheap. But these figures also point to a problem: EV drivers don’t trust public chargers.

At present, Australia has about 3,700 public chargers nationwide. Each charging station typically supports one or two EVs, often offering different charging speeds. By contrast, there are around 6,600 service stations, with the ability to fuel multiple vehicles at once.

Other countries have much larger charger networks. The United Kingdom has more than 40,000 and Canada 16,000. China, the world leader, has almost 10 million.

Outside major Australian cities, chargers are harder to find and are often broken or in use. Chargers are usually not staffed, meaning there’s no one watching to prevent vandalism or organise maintenance.

EV plugs are not yet standardised. Some plugs may not be available, and using chargers isn’t always easy. By contrast, petrol cars use standard nozzles, payment is simpler and staff and CCTV presence discourages vandalism and ensures the pumps work.

If a petrol car runs out of fuel, the problem can be solved with a lift and a jerry can. But if your EV runs flat in a rural area because you can’t find a charger, you may have to get it towed.

This lack of reliability is more than just a logistical hurdle — it’s a psychological barrier.

Psychological roadblocks

A recent study found the fear of running out of charge was a major psychological barrier to buying an EV – particularly for rural and regional Australians, who drive longer distances. As long as chargers remain unreliable or located too far apart, this anxiety will persist.

In Australia, it’s easy to find reports of broken chargers, long queues at charging stations, gaps in the rural network and personal anecdotes of EV owners struggling to find a way to charge.

A 2023 survey found almost 70% of EV owners had come across an inoperable charger at least once over the previous six months.

What can Australia take from overseas experience?

Australia’s government wants to increase EV uptake. While EVs are getting cheaper, the supporting infrastructure isn’t good enough yet to make them the norm.

Across the European Union, chargers are being installed every 60km along major highways and efforts are being made to tackle psychological barriers to uptake.

Federal and state governments in the United States have invested heavily in filling gaps in the charger network and working with consumers to encourage more sustainable commuting.

Choosing a hybrid is rational but not ideal

It should be no surprise more Australians are buying hybrids as a safety net, given there are plenty of service stations and not as many EV chargers. City driving can allow near-total use of the electric motor, while longer trips still require petrol.

The choice is rational. But it’s not ideal from an environmental point of view. Traditional hybrids are still largely powered by an internal combustion engine, while PHEVs can run as electric for longer but still use their combustion engines.

While plug-ins have lower emissions than traditional vehicles, they often fail to deliver the full emissions savings drivers and regulators might hope for. Many drivers don’t charge regularly and rely instead on petrol.

Chargers aren’t the only factor, of course. A tax break for PHEVs boosted their popularity for several years before ending in April, while sales of Tesla EVs have fallen off a cliff due to the unpopularity of owner Elon Musk.

What needs to change?

The solutions are straightforward: expand the charger network, especially in regional and rural areas. Improve maintenance schedules and ensure existing chargers are reliable. Make sure data on their availability is accessible in real time so drivers can avoid anxiety and frustration. Counter EV misinformation and anecdotal biases with information campaigns.

When EV ownership and charging in Australia is practical and low risk, the sluggish EV transition will accelerate. But until then, many drivers will keep buying hybrids as a compromise.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

But range isn’t the real issue. The average range of a new electric vehicle (EV) is more than 450 kilometres, and top models offer more than 700km per charge. By contrast, the average car is driven about 33km per day in Australia as of 2020.

What’s really going on is charger anxiety – the question of whether you can find somewhere reliable to recharge when you’re away from home. Australia’s public chargers are not common enough or reliable enough to give motorists certainty they can find a place to recharge.

This is why many drivers are hedging their bets. Rather than embracing battery-electric vehicles, many Australian drivers are opting for hybrids as well as plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), which couple a smaller battery with an internal combustion engine. Hybrids and PHEVs accounted for almost 20% of new car sales from July–September last year, compared to 6.5% for fully electric vehicles.

Labor’s reelection could lead to better charging infrastructure. Last term, the federal government set a goal of a fast charging station every 150km along major highways, while state governments are also building more. But so far, these efforts aren’t enough to ensure Australia has reliable chargers in the right locations. Until then, cautious drivers will buy hybrids.

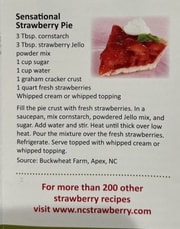

Australia’s charger network has expanded, but many drivers are anxious about availability and reliability. Stepan Skorobogadko/Shutterstock

Public chargers matter

EV owners charge their cars at home an estimated 70–85% of the time. They use public chargers just 10–20% of the time and workplace charging 6–10% of the time.

This makes sense – home charging is reliable and cheap. But these figures also point to a problem: EV drivers don’t trust public chargers.

At present, Australia has about 3,700 public chargers nationwide. Each charging station typically supports one or two EVs, often offering different charging speeds. By contrast, there are around 6,600 service stations, with the ability to fuel multiple vehicles at once.

Other countries have much larger charger networks. The United Kingdom has more than 40,000 and Canada 16,000. China, the world leader, has almost 10 million.

Outside major Australian cities, chargers are harder to find and are often broken or in use. Chargers are usually not staffed, meaning there’s no one watching to prevent vandalism or organise maintenance.

EV plugs are not yet standardised. Some plugs may not be available, and using chargers isn’t always easy. By contrast, petrol cars use standard nozzles, payment is simpler and staff and CCTV presence discourages vandalism and ensures the pumps work.

If a petrol car runs out of fuel, the problem can be solved with a lift and a jerry can. But if your EV runs flat in a rural area because you can’t find a charger, you may have to get it towed.

This lack of reliability is more than just a logistical hurdle — it’s a psychological barrier.

Psychological roadblocks

A recent study found the fear of running out of charge was a major psychological barrier to buying an EV – particularly for rural and regional Australians, who drive longer distances. As long as chargers remain unreliable or located too far apart, this anxiety will persist.

In Australia, it’s easy to find reports of broken chargers, long queues at charging stations, gaps in the rural network and personal anecdotes of EV owners struggling to find a way to charge.

A 2023 survey found almost 70% of EV owners had come across an inoperable charger at least once over the previous six months.

What can Australia take from overseas experience?

Australia’s government wants to increase EV uptake. While EVs are getting cheaper, the supporting infrastructure isn’t good enough yet to make them the norm.

Across the European Union, chargers are being installed every 60km along major highways and efforts are being made to tackle psychological barriers to uptake.

Federal and state governments in the United States have invested heavily in filling gaps in the charger network and working with consumers to encourage more sustainable commuting.

Choosing a hybrid is rational but not ideal

It should be no surprise more Australians are buying hybrids as a safety net, given there are plenty of service stations and not as many EV chargers. City driving can allow near-total use of the electric motor, while longer trips still require petrol.

The choice is rational. But it’s not ideal from an environmental point of view. Traditional hybrids are still largely powered by an internal combustion engine, while PHEVs can run as electric for longer but still use their combustion engines.

While plug-ins have lower emissions than traditional vehicles, they often fail to deliver the full emissions savings drivers and regulators might hope for. Many drivers don’t charge regularly and rely instead on petrol.

Chargers aren’t the only factor, of course. A tax break for PHEVs boosted their popularity for several years before ending in April, while sales of Tesla EVs have fallen off a cliff due to the unpopularity of owner Elon Musk.

What needs to change?

The solutions are straightforward: expand the charger network, especially in regional and rural areas. Improve maintenance schedules and ensure existing chargers are reliable. Make sure data on their availability is accessible in real time so drivers can avoid anxiety and frustration. Counter EV misinformation and anecdotal biases with information campaigns.

When EV ownership and charging in Australia is practical and low risk, the sluggish EV transition will accelerate. But until then, many drivers will keep buying hybrids as a compromise.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.