New Aged Care Shake-Up Keeps Seniors at Home – Lifeline or Letdown?

Australia is quietly revolutionising the way our elders receive care. New aged care reforms promise to help seniors stay in their own homes longer, sparing many the upheaval of moving into nursing homes.

For families with ageing parents, this sounds like welcome news – finally, Mum and Dad can stay in the comfort of home a bit longer. But as with any big change, there’s a catch (or two). Will keeping seniors at home be the lifeline it’s intended to be, or could it become a burden on stretched families and a housing market starved for supply? It’s a question sparking lively debate over cuppas in retirement villages and living rooms alike. Before we celebrate (or panic), let’s unpack what these reforms actually do, how they affect older Australians directly, and why some experts are cheering, while others remain sceptical.

So put the kettle on and get comfy. We’re diving into the new aged care laws: the good, the bad, and the yet-to-be-determined. On the surface, the changes are about independence and dignity for seniors. Look a little deeper, though, and you’ll find concerns about delays, costs, and even an impact on the nation’s housing crunch. Let’s explore both sides of this story in plain English – no bureaucratic jargon, just the facts, a bit of analysis, and maybe a dash of Aussie candour.

At the heart of the reforms is a new program called Support at Home, slated to launch nationwide on 1 November 2025 after a slight delay for fine-tuning. This program is set to replace the current jumble of in-home aged care schemes – things like Home Care Packages and Short-Term Restorative Care – with one streamlined system. Think of it as a one-stop shop for all the help seniors might need at home, from nursing visits to help with the vacuuming.

The idea is to simplify a fragmented system, speed up access to services, and give people more flexibility in choosing care. For older Australians, that could mean less paperwork and waiting, and more control over the support they get.

So, what exactly is changing? The government’s plan comes with a suite of updates. Here are the key ones to know:

For many seniors, the appeal of these changes is clear: ageing in place. Staying in the house you know and love, keeping your routines and community connections, with support coming to you – it sounds ideal.

“Ageing-in-place can be an excellent option for older Australians who wish to stay in their longstanding homes and communities,” says Natalie Yan-Chatonsky, an advocate for positive ageing. Remaining in familiar surroundings helps people maintain independence, reduce loneliness, and improve overall quality of life. In theory, the new program makes that easier and more affordable than before.

On paper, it’s a big win for senior independence. As one government minister put it, it’s a “once-in-a-generation reform” aiming to deliver “high quality, world-class aged care services to older Australians who have built this community”.

If this all sounds a bit too good, you’re not wrong to raise an eyebrow. In reality, aged care in Australia is a system already under strain, and these reforms – while promising – aren’t a magic fix overnight.

One immediate issue is timing. The Support at Home program was supposed to kick off in July 2025, but got pushed back four months to November. The official reason was to “give providers more time to prepare” and ensure a smooth rollout.

Fair enough – but advocates worry this delay could worsen the existing backlog of seniors waiting for help at home. And that backlog is no small thing: roughly 80,000 older Australians are already in the queue for home care packages, some waiting a year or more for essential services like help with cooking, cleaning and personal care.

Source: ABC News (Australia) / YouTube

In fact, a group of MPs and seniors’ advocates recently warned that “people are dying on the waitlist” for home care. It’s not just a figure of speech.

One 93-year-old woman in Canberra quipped “I’m going to be dead by then” upon learning she’d wait 6–9 months for her high-level care package. Tragically, she was right – she passed away before help arrived, never getting the support she needed in her final months.

Stories like that put a human face on these reforms. The government may promise that more funding and a new system will shorten wait times, but seniors and their families are understandably anxious.

As independent MP Helen Haines bluntly noted, “the longer that they wait, the higher the chances are of further deterioration… and premature entry into residential aged care.” In other words, delays can be dangerous.

Then there’s the question of workforce and support quality. It’s great to promise more care at home – but will there be enough trained carers and nurses to actually deliver it? Even now, aged care providers struggle with staff shortages and high demand. Without boosting the care workforce, more “packages” might just mean more waiting.

As one industry leader, Tom Symondson of Aged & Community Care Providers, warned, if packages are held up until November, the waitlist could balloon to over 100,000 people. The government is under pressure to bridge the gap – some are calling for 20,000 interim home care packages to be released ASAP – but it remains to be seen if stopgap measures will come.

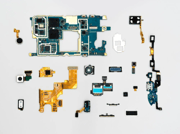

And even once services do kick in, living at home isn’t without its challenges for seniors. Many older folks’ houses aren’t designed for ageing safely – think stairs, slippery bathrooms, high shelves. Simple hazards can become big risks.

Source: ABC News (Australia) / YouTube

“If they choose to remain in their homes, they need to ensure it’s modified to prevent falls,” Yan-Chatonsky cautions, noting that 6 out of 10 falls for older people happen at home. Home modifications (grab rails, better lighting, ramps instead of steps) are crucial to make ageing-in-place viable. The new program does emphasise home mods, but it takes time and money to implement these changes widely.

Moreover, staying at home can sometimes lead to social isolation or caregiver burnout. As mobility declines, seniors may go out less and risk becoming lonely or depressed – ironically undermining that promised “quality of life” boost.

Families often end up filling the gaps in care: checking in daily, doing grocery runs, helping with showers, or managing medications. This can be “emotionally, physically and financially taxing” for adult children carers, especially those in the so-called “sandwich generation” juggling jobs, kids and elder care at once.

For example, one Melbourne man named Nathan shared how he tried to keep his elderly father at home with in-home support, but gaps in services and his dad’s worsening dementia eventually made it unsafe. “Despite having access to some in-home support…, it unfortunately meant he had to move out of his home,” Nathan said, after many distressing incidents and an overwhelming caring load on the family. Navigating the aged care system was another ordeal – at one point he was hit with an unexpected $40,000 aged care fee, simply because he wasn’t aware of all the fine print.

These real-world issues highlight an uncomfortable truth: It’s not enough to want to keep seniors at home; we need a system that can actually support them (and their families) in practice. The government’s new plan aims to help, but many fear it’s just “entrenching the current system – one that already struggles to keep up with demand”. Without deeper fixes, we could end up with more seniors stuck waiting, more family caregivers stretched thin, and still not enough safe, suitable options for those who do eventually need a higher level of care.

As one aged care advocate summed it up, “we are still avoiding the real structural and funding issues needed to improve the sector at large”. In other words, the new laws might buy a bit of time, but they’re not a cure-all for what ails our aged care system.

Let’s talk about the hip-pocket impact, because money matters – especially on a pension. One aspect of the reforms causing nerves among older Aussies is the new fee structure. Under the current system, many home care services for pensioners are heavily subsidised or free (for instance, the Commonwealth Home Support Program often only asks for a token contribution).

That’s about to change. The Support at Home program introduces national co-payments for services that used to come gratis for pensioners. Essentially, if you’re getting help at home, you’ll likely pay something out-of-pocket – how much depends on your financial situation.

Here’s the breakdown in plain terms: The government has split home care into three categories – clinical care (health services like nursing or physio), independence support (personal care such as showering, dressing, taking meds) and everyday living support (domestic help like cleaning, gardening, meals).

Clinical care stays free (fully covered by the government) for everyone. But for the other two categories, you pay a percentage of the cost, determined by a means test.

If you’re a full Age Pensioner, you’ll pay 5% of the cost of personal care and 17.5% of domestic help – so not huge, but a new expense nonetheless.

If you’re on a part pension or a self-funded retiree, the co-pay scales up – wealthier seniors could end up covering 50% of their personal care costs and 80% of cleaning/gardening costs out-of-pocket.

For the first time, the government is also setting maximum prices for services to prevent overcharging, which is a plus for consumer protection. Still, the idea of “paying for a shower” has some seniors furious. “We think showers should be considered as part of clinical care – not a luxury,” argues Craig Gear of the Older Persons Advocacy Network, noting that basic hygiene shouldn’t depend on ability to pay.

The government insists no current recipient will be worse off immediately – they’ve promised a “no worse off” guarantee, meaning if you’re already on a package, you won’t suddenly have to pay more on Day 1. And for anyone genuinely unable to afford the fees, there’s a hardship provision to waive costs. But many seniors remain skeptical.

They’ve worked all their lives and now they’re elderly they have to sit there and justify their existence?” says Christina Tsobanis, who cares for her mum with Alzheimer’s. She worries people will be too proud or confused by red tape to apply for fee relief, effectively taxing the old and vulnerable. In her case, she calculated that if her mum weren’t already on an existing package, their family would be paying about $200 extra per fortnight in co-payments under the new scheme. That kind of added cost could force them to cut back on care services – the exact opposite of the policy’s intention.

Others have expressed even blunter criticism. One elderly Australian, “Sam,” didn’t mince words, calling the new home care fees “dismal, pathetic, horrific… a very sad reflection on how society treats the elderly.” He believes many pensioners will not qualify for hardship exemptions and thus will effectively bear what feels like a stealthy pension cut.

Anxiety about affordability is running high in senior communities; financial advisors report that confusion and worry about the new fees are common topics in their sessions. Jim Moraitis, who runs an aged care advice service, says “the overwhelming sentiment… is one of deep concern, anxiety and frustration” about the looming co-payments. Even paying an extra $10–30 a week can be a stretch for someone on a full pension of ~$1,100 a fortnight – especially with the cost of groceries, utilities and rent all up these days.

And it’s not just in-home care where the hip-pocket pressure is rising. The reforms also tweak the costs for residential aged care (nursing homes), which could hit many middle-class seniors in the future.

Starting November 2025, the government is changing the means test thresholds. Right now, you only pay the maximum means-tested care fees in a nursing home if you have over about $2 million in assets. Under the new rules, that drops to $1 million in assets. In practical terms, that means many more people will have to pay the top rate for their aged care – fees up to ~$42,000 per year (with a lifetime cap around $130k, up from $82k today).

A lot of ordinary home-owning Aussies – not just the ultra-rich – could cross that $1m asset line when you include the family home value. It’s a big shift in who bears the cost of aged care. “More people will now pay the maximum co-contribution towards their cost of care,” explains aged care adviser Kerri Mendl, noting the intent is to make those who can afford it pay a greater share.

There’s also a new rule on those hefty Refundable Accommodation Deposits (RADs) that nursing homes charge (often hundreds of thousands of dollars, like a bond). Currently, if you leave or pass away, that RAD is fully refunded to you or your estate (minus any fees).

But for new residents from Nov 2025 onward, facilities will be allowed to retain 2% of the RAD per year for the first five years. That could mean losing up to 10% of your deposit permanently if you stay in care 5+ years. For example, on a $400,000 RAD, up to $40k might be kept by the provider – money that otherwise would’ve gone back to your kids or estate.

It’s another way the financial burden is subtly shifting. Seniors who are considering a move to residential care soon are being gently advised that locking in before these rules change could save a lot of money. Not exactly pressure, but… something to chew on.

All these changes paint a complex picture. On one hand, asking those who can afford it to contribute more is arguably fair and necessary – Australia’s population is ageing, and the cost of aged care (whether at home or in facilities) is skyrocketing. The government can’t foot the entire bill without ballooning costs to taxpayers, so these means-tested contributions aim to make the system sustainable. Indeed, the federal government expects to save $12.6 billion over 11 years from the aged care reforms, partly thanks to these new user contributions. That money, they say, will be reinvested to improve services and fund the expansion of care packages.

On the other hand, it’s a delicate balance to ensure seniors aren’t priced out of care or impoverished by it. If fees are set too high or relief too hard to get, some older people might opt out of services to save money, soldiering on alone until a crisis hits. That could backfire tragically – leading to worse health outcomes and even more expensive hospital or nursing home care down the track. So the stakes are high: get the balance right, and we have a stronger system; get it wrong, and we simply shift problems around.

Beyond the immediate world of aged care, these reforms have a ripple effect on another hot-button issue: Australia’s housing crisis. You might not think aged care policy could impact housing affordability, but in a roundabout way, it can.

Here’s how: If more seniors stay in their homes longer, fewer houses get freed up for younger families to buy or rent. Typically, when an elderly person moves into aged care (or downsizes to a retirement unit), their former home often goes on the market, adding to housing supply. But if Mum and Dad age in place until the very end, that family home stays off the market, sometimes for many extra years. In a country already grappling with housing shortages and sky-high prices, some worry this trend could further squeeze the market.

It’s a sensitive point – nobody is suggesting seniors should be rushed out of their homes just to free up real estate. But it’s an economic reality that demographers and property experts are watching. In fact, the original news article cheekily asked: “Will it ease the housing crisis?” and answered that keeping parents at home “will continue to put pressure on an already tight housing market”.

Australia has a lot of big, mostly-empty houses owned by older folks whose kids have moved out. According to recent surveys, nearly 7 in 10 “empty nester” homeowners have no intention of downsizing despite all the talk of housing shortages. They prefer to stay put – understandable, given emotional attachments and the hassle/cost of moving.

This means thousands of larger homes stay occupied by one or two seniors, while younger families hunt for space. In South Australia, for instance, nearly 80% of over-60 homeowners said they won’t be selling the family home to downsize. Nationally, the trend is similar. The upshot: expecting older Aussies to “free up” housing by moving out is largely wishful thinking under current conditions.

The new aged care reforms could reinforce that status quo. By providing more support and financial incentives to remain at home, the policy might encourage seniors to hold on to the family property even longer. For the seniors themselves, that’s a win – they get to enjoy their home and community in their twilight years. For the housing market, it’s one less listing, which over time does have an impact. Some experts call this the “blocking” effect – not a nice term, but it describes how a lack of downsizing by older generations can slow the circulation of housing stock.

The Retirement Living Council (which represents retirement village developers) has been vocal about this. They argue that “prehistoric policies are locking older Australians in large family homes during a housing crisis” and that we need to remove disincentives for seniors to “right-size” their living arrangements. For example, rules that cause someone to lose part of their pension or pay a lot of stamp duty if they sell their home can discourage moving. The Council estimates that with the right incentives (like adjusting pension asset tests and offering stamp duty breaks), up to 94,000 seniors could downsize or move into retirement communities without financial penalty – potentially freeing up thousands of homes for younger families.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. There’s another housing angle: multigenerational living is on the rise, which can actually increase housing efficiency in some cases. More Aussies are embracing the idea of several generations under one roof – parents, kids, and grandparents living together or in a duplex-style arrangement.

In fact, about 20% of Australians now live in multigenerational households, and the biggest driver recently is older parents moving in with their adult children. Sometimes this happens because the family would rather care for Grandpa at home than see him in a nursing home (especially if the nursing home costs a fortune or has a bad rep). Other times it’s simply cultural or economic common sense: why maintain two big houses when the family could share one?

By combining households, a multigenerational family might actually free up one property to rent or sell. For example, if Grandma sells her house and moves in with the family, that’s one more house on the market (or available for another family to rent), even though your household got bigger.

The new aged care changes could indirectly encourage some of this. If home care services make it feasible, an elderly parent might stay in their home longer – or perhaps an alternative is the parent moves into your home and receives care there. Many families are choosing the latter for practical reasons.

As researcher Edgar Liu from UNSW found, “many people can’t bear the thought of sending mum to a nursing home, or they don’t want to spend a lot of money on [aged care]… plus, childcare is expensive, so if mum moves in, they can help with the grandkids”. It’s like solving two problems at once: Grandma gets family care (and maybe helps with babysitting), and the family saves on childcare and aged care fees.

During COVID, we also saw a spike in young adults boomeranging back home and elders moving in with family, due to both health fears and finances. Multigenerational living is no longer a rarity; it’s making a comeback out of necessity and preference. Home builders even report more clients asking for designs with a self-contained “granny flat” or dual living areas for privacy.

Of course, not every senior has family able or willing to live together, nor is every home suitable for multiple generations. And truth be told, not every older person wants to bunk in with the kids (independence goes both ways!). But it’s a trend worth noting as we consider the broader effects of ageing-in-place.

The big picture is this: keeping seniors at home longer is largely positive for their wellbeing, but it does pose challenges for housing supply. Policymakers are being nudged to find creative solutions – like building more retirement communities and age-friendly units that seniors want to move into.

The idea is if older Australians can downsize into attractive, affordable retirement living, they free up larger homes and possibly get better support. A recent report suggested that building an extra 50,000 retirement units by 2030 could reduce Australia’s housing shortfall by two-thirds. And those who’ve moved to modern retirement villages often report being happier, healthier and more social – it’s not “aged care” but a lifestyle choice. The Queensland Government even put $350 million toward such housing projects, seeing it as part of the housing crisis puzzle.

In summary, the new aged care laws are a double-edged sword for housing. They prioritise people (seniors’ comfort) over properties (market supply), as they probably should. Yet the housing crunch is real, and as more baby boomers choose to stay in the family home, we’ll need other ways to make housing available for younger generations. It’s a complex intergenerational dance – one that Australia is just beginning to choreograph.

With all these reforms on the horizon, what should you do if you’re a senior or have ageing parents? The changes aren’t just lofty policies; they will affect real decisions in the coming months and years. Experts advise being proactive rather than waiting for a crisis.

Kerri Mendl, an aged care financial adviser, suggests families have the “uncomfortable conversations” early. It’s much easier to talk about options and preferences before a health emergency forces your hand. Here are a few practical steps experts recommend to get ready for the new aged care era:

Most importantly, keep the elder involved in decisions as much as possible. It’s their life. The goal of these reforms, after all, is to empower older Australians to live with dignity, whether at home or in care. Sometimes that might mean lovingly challenging a parent’s insistence on staying put when it’s clearly not working. It’s a balancing act: respecting their wishes, but also ensuring they’re safe and not miserable.

One commentator described her own 97-year-old grandfather who steadfastly refused to leave his too-large house, even though he could no longer manage the garden or the stairs or even collect the mail safely. All the reasons he wanted to stay (independence, familiarity) had faded away, yet he was “happy with his self-imposed house arrest” – and the family let him be, for now. Situations like that are common, and they’re emotionally tough. The new in-home support might prolong those scenarios, for better or worse.

Stepping back, it’s clear that these reforms – significant as they are – won’t fix everything. They aim to buy time for the system to catch up, but Australia’s aged care challenges run deeper. The Royal Commission into Aged Care spent years investigating and concluded in 2021 that the system was failing and in dire need of overhaul.

Many of the current changes stem from its recommendations – like a new Aged Care Act focused on rights and quality, more home care packages, better staffing ratios in nursing homes, etc. So this is part of a broader reform journey, not the final destination.

One lingering question is funding. Aged care is expensive, and as our population ages (the proportion of Australians over 85 is set to double in the next 25 years), the costs will explode. The reforms raise more contributions from users, but will that money be enough and well-spent? The government touts that it’s investing billions more and setting higher standards.

Yet some advocates feel we’re still avoiding hard truths about who will pay for aged care in the long run and how to make the system deliver “dignified, community-focused and future-ready” care. The vision is wonderful: small, homey aged care facilities integrated in communities, where elders have autonomy, social connection, and top-notch care – places people want to live in if they can’t stay at home. Achieving that widespread will require not just tweaking fees but bold structural changes, possibly new taxes or insurance schemes (debates for another day).

For now, the Support at Home program and associated reforms are a step in the right direction in many ways. They respond to what older people say they want – to stay home, to have more choices, and not to be forced into care because of bureaucratic hurdles or lack of support. They also push those who can contribute to do so, which could shore up the system’s finances.

But implementation is everything. If the rollout is smooth, waitlists shrink, and seniors find it easier to get the help they need without going broke, then these reforms could truly be a lifeline that lets more of us age with dignity where we belong. If not – if delays persist, costs deter people from seeking help, or families are left carrying an even heavier load – then the promise of ageing-in-place might prove to be a bit of a letdown, or at least a mixed blessing.

As one financial expert mused, “even with these proposed changes, [the ideal system] is still a way off.” We’re in a transition period. It’s hopeful and hectic all at once.

Aged care workers are doing their utmost on the ground, and they deserve credit – no reform is possible without their dedication. Yet they too need more hands on deck and better resources, whether in homes or facilities. It’s telling that crossbench MPs had to remind the government that “older Australians built this country” and deserve to age with dignity at home – a principle no one disagrees with, but one that’s easy to lose in the maze of policy details.

So, what do we make of it all? The new aged care laws will definitely change the game for many Australian seniors and their families. They bring a mix of encouragement and caution. On one side, there’s real optimism: more support to live at home, more funding for those who need it most, and a long overdue simplification of aged care services. On the other, there are valid concerns: potential service shortfalls, new fees nibbling at fixed incomes, and the question of whether we’re just papering over deeper cracks in the system (all while our housing woes rumble on).

For our senior readers, especially, this is personal. It’s about where and how you’ll live your later years – and who will be by your side. These reforms aim to tilt the balance toward home, community, and family. But we should be clear-eyed: supporting our elders at home will take effort from all of everyone – government, care providers, families, and the seniors themselves. It might mean adjusting expectations (maybe the family home will need to be sold someday, or maybe Junior will move into the spare room). It might mean embracing some new costs in return for better care. And it will certainly mean staying informed and engaged with the changes as they roll out.

What do you think – are we on the right track with these aged care reforms, or just kicking the can down the road on bigger issues?

READ MORE: Hard to Handle: How Everyday Products Are Failing Older Australians

For families with ageing parents, this sounds like welcome news – finally, Mum and Dad can stay in the comfort of home a bit longer. But as with any big change, there’s a catch (or two). Will keeping seniors at home be the lifeline it’s intended to be, or could it become a burden on stretched families and a housing market starved for supply? It’s a question sparking lively debate over cuppas in retirement villages and living rooms alike. Before we celebrate (or panic), let’s unpack what these reforms actually do, how they affect older Australians directly, and why some experts are cheering, while others remain sceptical.

So put the kettle on and get comfy. We’re diving into the new aged care laws: the good, the bad, and the yet-to-be-determined. On the surface, the changes are about independence and dignity for seniors. Look a little deeper, though, and you’ll find concerns about delays, costs, and even an impact on the nation’s housing crunch. Let’s explore both sides of this story in plain English – no bureaucratic jargon, just the facts, a bit of analysis, and maybe a dash of Aussie candour.

The Promise of ‘Support at Home’

At the heart of the reforms is a new program called Support at Home, slated to launch nationwide on 1 November 2025 after a slight delay for fine-tuning. This program is set to replace the current jumble of in-home aged care schemes – things like Home Care Packages and Short-Term Restorative Care – with one streamlined system. Think of it as a one-stop shop for all the help seniors might need at home, from nursing visits to help with the vacuuming.

The idea is to simplify a fragmented system, speed up access to services, and give people more flexibility in choosing care. For older Australians, that could mean less paperwork and waiting, and more control over the support they get.

So, what exactly is changing? The government’s plan comes with a suite of updates. Here are the key ones to know:

- More funding for higher needs: If you have significant care needs, you could get up to $78,000 per year towards in-home support – a big boost from the old cap of ~$60k.

- Means-tested fees: Everyone receiving home care – even full pensioners – may have to chip in a co-payment for certain services (like help with showering, cleaning or gardening), based on your income and assets. In other words, those who can afford to pay a bit, will pay a bit.

- Better access to equipment & mods: Need a ramp, rails, or other home modifications to stay safe? The new program promises greater access to equipment and home upgrades to prevent falls and make homes age-friendly.

- Flexibility to opt in and out: Life isn’t static – maybe you need extra help after a hospital stay, then less later. Support at Home will let seniors start or stop services more easily as their needs change, without jumping through so many hoops.

For many seniors, the appeal of these changes is clear: ageing in place. Staying in the house you know and love, keeping your routines and community connections, with support coming to you – it sounds ideal.

“Ageing-in-place can be an excellent option for older Australians who wish to stay in their longstanding homes and communities,” says Natalie Yan-Chatonsky, an advocate for positive ageing. Remaining in familiar surroundings helps people maintain independence, reduce loneliness, and improve overall quality of life. In theory, the new program makes that easier and more affordable than before.

On paper, it’s a big win for senior independence. As one government minister put it, it’s a “once-in-a-generation reform” aiming to deliver “high quality, world-class aged care services to older Australians who have built this community”.

Not So Fast: The Reality on the Ground

If this all sounds a bit too good, you’re not wrong to raise an eyebrow. In reality, aged care in Australia is a system already under strain, and these reforms – while promising – aren’t a magic fix overnight.

One immediate issue is timing. The Support at Home program was supposed to kick off in July 2025, but got pushed back four months to November. The official reason was to “give providers more time to prepare” and ensure a smooth rollout.

Fair enough – but advocates worry this delay could worsen the existing backlog of seniors waiting for help at home. And that backlog is no small thing: roughly 80,000 older Australians are already in the queue for home care packages, some waiting a year or more for essential services like help with cooking, cleaning and personal care.

Source: ABC News (Australia) / YouTube

In fact, a group of MPs and seniors’ advocates recently warned that “people are dying on the waitlist” for home care. It’s not just a figure of speech.

One 93-year-old woman in Canberra quipped “I’m going to be dead by then” upon learning she’d wait 6–9 months for her high-level care package. Tragically, she was right – she passed away before help arrived, never getting the support she needed in her final months.

Stories like that put a human face on these reforms. The government may promise that more funding and a new system will shorten wait times, but seniors and their families are understandably anxious.

As independent MP Helen Haines bluntly noted, “the longer that they wait, the higher the chances are of further deterioration… and premature entry into residential aged care.” In other words, delays can be dangerous.

Then there’s the question of workforce and support quality. It’s great to promise more care at home – but will there be enough trained carers and nurses to actually deliver it? Even now, aged care providers struggle with staff shortages and high demand. Without boosting the care workforce, more “packages” might just mean more waiting.

As one industry leader, Tom Symondson of Aged & Community Care Providers, warned, if packages are held up until November, the waitlist could balloon to over 100,000 people. The government is under pressure to bridge the gap – some are calling for 20,000 interim home care packages to be released ASAP – but it remains to be seen if stopgap measures will come.

And even once services do kick in, living at home isn’t without its challenges for seniors. Many older folks’ houses aren’t designed for ageing safely – think stairs, slippery bathrooms, high shelves. Simple hazards can become big risks.

Source: ABC News (Australia) / YouTube

“If they choose to remain in their homes, they need to ensure it’s modified to prevent falls,” Yan-Chatonsky cautions, noting that 6 out of 10 falls for older people happen at home. Home modifications (grab rails, better lighting, ramps instead of steps) are crucial to make ageing-in-place viable. The new program does emphasise home mods, but it takes time and money to implement these changes widely.

Moreover, staying at home can sometimes lead to social isolation or caregiver burnout. As mobility declines, seniors may go out less and risk becoming lonely or depressed – ironically undermining that promised “quality of life” boost.

Families often end up filling the gaps in care: checking in daily, doing grocery runs, helping with showers, or managing medications. This can be “emotionally, physically and financially taxing” for adult children carers, especially those in the so-called “sandwich generation” juggling jobs, kids and elder care at once.

For example, one Melbourne man named Nathan shared how he tried to keep his elderly father at home with in-home support, but gaps in services and his dad’s worsening dementia eventually made it unsafe. “Despite having access to some in-home support…, it unfortunately meant he had to move out of his home,” Nathan said, after many distressing incidents and an overwhelming caring load on the family. Navigating the aged care system was another ordeal – at one point he was hit with an unexpected $40,000 aged care fee, simply because he wasn’t aware of all the fine print.

These real-world issues highlight an uncomfortable truth: It’s not enough to want to keep seniors at home; we need a system that can actually support them (and their families) in practice. The government’s new plan aims to help, but many fear it’s just “entrenching the current system – one that already struggles to keep up with demand”. Without deeper fixes, we could end up with more seniors stuck waiting, more family caregivers stretched thin, and still not enough safe, suitable options for those who do eventually need a higher level of care.

As one aged care advocate summed it up, “we are still avoiding the real structural and funding issues needed to improve the sector at large”. In other words, the new laws might buy a bit of time, but they’re not a cure-all for what ails our aged care system.

Paying the Price: What Do These Changes Cost Seniors?

Let’s talk about the hip-pocket impact, because money matters – especially on a pension. One aspect of the reforms causing nerves among older Aussies is the new fee structure. Under the current system, many home care services for pensioners are heavily subsidised or free (for instance, the Commonwealth Home Support Program often only asks for a token contribution).

That’s about to change. The Support at Home program introduces national co-payments for services that used to come gratis for pensioners. Essentially, if you’re getting help at home, you’ll likely pay something out-of-pocket – how much depends on your financial situation.

Here’s the breakdown in plain terms: The government has split home care into three categories – clinical care (health services like nursing or physio), independence support (personal care such as showering, dressing, taking meds) and everyday living support (domestic help like cleaning, gardening, meals).

Clinical care stays free (fully covered by the government) for everyone. But for the other two categories, you pay a percentage of the cost, determined by a means test.

If you’re a full Age Pensioner, you’ll pay 5% of the cost of personal care and 17.5% of domestic help – so not huge, but a new expense nonetheless.

If you’re on a part pension or a self-funded retiree, the co-pay scales up – wealthier seniors could end up covering 50% of their personal care costs and 80% of cleaning/gardening costs out-of-pocket.

For the first time, the government is also setting maximum prices for services to prevent overcharging, which is a plus for consumer protection. Still, the idea of “paying for a shower” has some seniors furious. “We think showers should be considered as part of clinical care – not a luxury,” argues Craig Gear of the Older Persons Advocacy Network, noting that basic hygiene shouldn’t depend on ability to pay.

The government insists no current recipient will be worse off immediately – they’ve promised a “no worse off” guarantee, meaning if you’re already on a package, you won’t suddenly have to pay more on Day 1. And for anyone genuinely unable to afford the fees, there’s a hardship provision to waive costs. But many seniors remain skeptical.

They’ve worked all their lives and now they’re elderly they have to sit there and justify their existence?” says Christina Tsobanis, who cares for her mum with Alzheimer’s. She worries people will be too proud or confused by red tape to apply for fee relief, effectively taxing the old and vulnerable. In her case, she calculated that if her mum weren’t already on an existing package, their family would be paying about $200 extra per fortnight in co-payments under the new scheme. That kind of added cost could force them to cut back on care services – the exact opposite of the policy’s intention.

Others have expressed even blunter criticism. One elderly Australian, “Sam,” didn’t mince words, calling the new home care fees “dismal, pathetic, horrific… a very sad reflection on how society treats the elderly.” He believes many pensioners will not qualify for hardship exemptions and thus will effectively bear what feels like a stealthy pension cut.

Anxiety about affordability is running high in senior communities; financial advisors report that confusion and worry about the new fees are common topics in their sessions. Jim Moraitis, who runs an aged care advice service, says “the overwhelming sentiment… is one of deep concern, anxiety and frustration” about the looming co-payments. Even paying an extra $10–30 a week can be a stretch for someone on a full pension of ~$1,100 a fortnight – especially with the cost of groceries, utilities and rent all up these days.

And it’s not just in-home care where the hip-pocket pressure is rising. The reforms also tweak the costs for residential aged care (nursing homes), which could hit many middle-class seniors in the future.

Starting November 2025, the government is changing the means test thresholds. Right now, you only pay the maximum means-tested care fees in a nursing home if you have over about $2 million in assets. Under the new rules, that drops to $1 million in assets. In practical terms, that means many more people will have to pay the top rate for their aged care – fees up to ~$42,000 per year (with a lifetime cap around $130k, up from $82k today).

A lot of ordinary home-owning Aussies – not just the ultra-rich – could cross that $1m asset line when you include the family home value. It’s a big shift in who bears the cost of aged care. “More people will now pay the maximum co-contribution towards their cost of care,” explains aged care adviser Kerri Mendl, noting the intent is to make those who can afford it pay a greater share.

There’s also a new rule on those hefty Refundable Accommodation Deposits (RADs) that nursing homes charge (often hundreds of thousands of dollars, like a bond). Currently, if you leave or pass away, that RAD is fully refunded to you or your estate (minus any fees).

But for new residents from Nov 2025 onward, facilities will be allowed to retain 2% of the RAD per year for the first five years. That could mean losing up to 10% of your deposit permanently if you stay in care 5+ years. For example, on a $400,000 RAD, up to $40k might be kept by the provider – money that otherwise would’ve gone back to your kids or estate.

It’s another way the financial burden is subtly shifting. Seniors who are considering a move to residential care soon are being gently advised that locking in before these rules change could save a lot of money. Not exactly pressure, but… something to chew on.

All these changes paint a complex picture. On one hand, asking those who can afford it to contribute more is arguably fair and necessary – Australia’s population is ageing, and the cost of aged care (whether at home or in facilities) is skyrocketing. The government can’t foot the entire bill without ballooning costs to taxpayers, so these means-tested contributions aim to make the system sustainable. Indeed, the federal government expects to save $12.6 billion over 11 years from the aged care reforms, partly thanks to these new user contributions. That money, they say, will be reinvested to improve services and fund the expansion of care packages.

On the other hand, it’s a delicate balance to ensure seniors aren’t priced out of care or impoverished by it. If fees are set too high or relief too hard to get, some older people might opt out of services to save money, soldiering on alone until a crisis hits. That could backfire tragically – leading to worse health outcomes and even more expensive hospital or nursing home care down the track. So the stakes are high: get the balance right, and we have a stronger system; get it wrong, and we simply shift problems around.

Homes and Housing: A Mixed Blessing

Beyond the immediate world of aged care, these reforms have a ripple effect on another hot-button issue: Australia’s housing crisis. You might not think aged care policy could impact housing affordability, but in a roundabout way, it can.

Here’s how: If more seniors stay in their homes longer, fewer houses get freed up for younger families to buy or rent. Typically, when an elderly person moves into aged care (or downsizes to a retirement unit), their former home often goes on the market, adding to housing supply. But if Mum and Dad age in place until the very end, that family home stays off the market, sometimes for many extra years. In a country already grappling with housing shortages and sky-high prices, some worry this trend could further squeeze the market.

It’s a sensitive point – nobody is suggesting seniors should be rushed out of their homes just to free up real estate. But it’s an economic reality that demographers and property experts are watching. In fact, the original news article cheekily asked: “Will it ease the housing crisis?” and answered that keeping parents at home “will continue to put pressure on an already tight housing market”.

Australia has a lot of big, mostly-empty houses owned by older folks whose kids have moved out. According to recent surveys, nearly 7 in 10 “empty nester” homeowners have no intention of downsizing despite all the talk of housing shortages. They prefer to stay put – understandable, given emotional attachments and the hassle/cost of moving.

This means thousands of larger homes stay occupied by one or two seniors, while younger families hunt for space. In South Australia, for instance, nearly 80% of over-60 homeowners said they won’t be selling the family home to downsize. Nationally, the trend is similar. The upshot: expecting older Aussies to “free up” housing by moving out is largely wishful thinking under current conditions.

The new aged care reforms could reinforce that status quo. By providing more support and financial incentives to remain at home, the policy might encourage seniors to hold on to the family property even longer. For the seniors themselves, that’s a win – they get to enjoy their home and community in their twilight years. For the housing market, it’s one less listing, which over time does have an impact. Some experts call this the “blocking” effect – not a nice term, but it describes how a lack of downsizing by older generations can slow the circulation of housing stock.

The Retirement Living Council (which represents retirement village developers) has been vocal about this. They argue that “prehistoric policies are locking older Australians in large family homes during a housing crisis” and that we need to remove disincentives for seniors to “right-size” their living arrangements. For example, rules that cause someone to lose part of their pension or pay a lot of stamp duty if they sell their home can discourage moving. The Council estimates that with the right incentives (like adjusting pension asset tests and offering stamp duty breaks), up to 94,000 seniors could downsize or move into retirement communities without financial penalty – potentially freeing up thousands of homes for younger families.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. There’s another housing angle: multigenerational living is on the rise, which can actually increase housing efficiency in some cases. More Aussies are embracing the idea of several generations under one roof – parents, kids, and grandparents living together or in a duplex-style arrangement.

In fact, about 20% of Australians now live in multigenerational households, and the biggest driver recently is older parents moving in with their adult children. Sometimes this happens because the family would rather care for Grandpa at home than see him in a nursing home (especially if the nursing home costs a fortune or has a bad rep). Other times it’s simply cultural or economic common sense: why maintain two big houses when the family could share one?

By combining households, a multigenerational family might actually free up one property to rent or sell. For example, if Grandma sells her house and moves in with the family, that’s one more house on the market (or available for another family to rent), even though your household got bigger.

The new aged care changes could indirectly encourage some of this. If home care services make it feasible, an elderly parent might stay in their home longer – or perhaps an alternative is the parent moves into your home and receives care there. Many families are choosing the latter for practical reasons.

As researcher Edgar Liu from UNSW found, “many people can’t bear the thought of sending mum to a nursing home, or they don’t want to spend a lot of money on [aged care]… plus, childcare is expensive, so if mum moves in, they can help with the grandkids”. It’s like solving two problems at once: Grandma gets family care (and maybe helps with babysitting), and the family saves on childcare and aged care fees.

During COVID, we also saw a spike in young adults boomeranging back home and elders moving in with family, due to both health fears and finances. Multigenerational living is no longer a rarity; it’s making a comeback out of necessity and preference. Home builders even report more clients asking for designs with a self-contained “granny flat” or dual living areas for privacy.

Of course, not every senior has family able or willing to live together, nor is every home suitable for multiple generations. And truth be told, not every older person wants to bunk in with the kids (independence goes both ways!). But it’s a trend worth noting as we consider the broader effects of ageing-in-place.

The big picture is this: keeping seniors at home longer is largely positive for their wellbeing, but it does pose challenges for housing supply. Policymakers are being nudged to find creative solutions – like building more retirement communities and age-friendly units that seniors want to move into.

The idea is if older Australians can downsize into attractive, affordable retirement living, they free up larger homes and possibly get better support. A recent report suggested that building an extra 50,000 retirement units by 2030 could reduce Australia’s housing shortfall by two-thirds. And those who’ve moved to modern retirement villages often report being happier, healthier and more social – it’s not “aged care” but a lifestyle choice. The Queensland Government even put $350 million toward such housing projects, seeing it as part of the housing crisis puzzle.

In summary, the new aged care laws are a double-edged sword for housing. They prioritise people (seniors’ comfort) over properties (market supply), as they probably should. Yet the housing crunch is real, and as more baby boomers choose to stay in the family home, we’ll need other ways to make housing available for younger generations. It’s a complex intergenerational dance – one that Australia is just beginning to choreograph.

Preparing for Change: What Seniors and Families Can Do

With all these reforms on the horizon, what should you do if you’re a senior or have ageing parents? The changes aren’t just lofty policies; they will affect real decisions in the coming months and years. Experts advise being proactive rather than waiting for a crisis.

Kerri Mendl, an aged care financial adviser, suggests families have the “uncomfortable conversations” early. It’s much easier to talk about options and preferences before a health emergency forces your hand. Here are a few practical steps experts recommend to get ready for the new aged care era:

- Get an Aged Care Assessment: If your parent (or you) is slowing down or having health issues, request an ACAT assessment sooner rather than later. This is the gateway to accessing any subsidised care at home. Given the waitlists, being “on the radar” early is wise.

- Review finances and assets: Have a clear picture of assets and income, and update Centrelink or DVA on any changes yearly. This matters for means testing – e.g. renting out a room, cashing investments, etc., can affect fees. Also, before gifting money or selling the house, get advice; such moves can impact aged care costs if done within 5 years of needing care.

- Sort out legal documents: Ensure there’s a valid Enduring Power of Attorney and guardianship paperwork in place, and that the right family members know where to find them. If Mum loses capacity, someone needs authority to handle finances and care decisions without legal hiccups.

- Assess the home’s suitability: Take an honest look at whether the current home is fit for ageing. Are there stairs that are becoming tricky? Is the big garden a burden? Is the area isolating? Sometimes, moving to a smaller, safer place or a retirement community can actually improve quality of life, even if it’s a tough sell emotionally. Every situation is different – some homes just need a few modifications; others might be downright hazardous for a 90-year-old.

- Consider professional advice: The aged care system is complex and about to change – don’t hesitate to consult an aged care specialist or financial planner who knows this field. They can model out costs under the new rules, help with paperwork, and ensure you don’t miss any entitlements. As Nathan’s story showed, getting good advice saved him from financial pitfalls.

Most importantly, keep the elder involved in decisions as much as possible. It’s their life. The goal of these reforms, after all, is to empower older Australians to live with dignity, whether at home or in care. Sometimes that might mean lovingly challenging a parent’s insistence on staying put when it’s clearly not working. It’s a balancing act: respecting their wishes, but also ensuring they’re safe and not miserable.

One commentator described her own 97-year-old grandfather who steadfastly refused to leave his too-large house, even though he could no longer manage the garden or the stairs or even collect the mail safely. All the reasons he wanted to stay (independence, familiarity) had faded away, yet he was “happy with his self-imposed house arrest” – and the family let him be, for now. Situations like that are common, and they’re emotionally tough. The new in-home support might prolong those scenarios, for better or worse.

The Bigger Picture: Aged Care’s Unfinished Business

Stepping back, it’s clear that these reforms – significant as they are – won’t fix everything. They aim to buy time for the system to catch up, but Australia’s aged care challenges run deeper. The Royal Commission into Aged Care spent years investigating and concluded in 2021 that the system was failing and in dire need of overhaul.

Many of the current changes stem from its recommendations – like a new Aged Care Act focused on rights and quality, more home care packages, better staffing ratios in nursing homes, etc. So this is part of a broader reform journey, not the final destination.

One lingering question is funding. Aged care is expensive, and as our population ages (the proportion of Australians over 85 is set to double in the next 25 years), the costs will explode. The reforms raise more contributions from users, but will that money be enough and well-spent? The government touts that it’s investing billions more and setting higher standards.

Yet some advocates feel we’re still avoiding hard truths about who will pay for aged care in the long run and how to make the system deliver “dignified, community-focused and future-ready” care. The vision is wonderful: small, homey aged care facilities integrated in communities, where elders have autonomy, social connection, and top-notch care – places people want to live in if they can’t stay at home. Achieving that widespread will require not just tweaking fees but bold structural changes, possibly new taxes or insurance schemes (debates for another day).

For now, the Support at Home program and associated reforms are a step in the right direction in many ways. They respond to what older people say they want – to stay home, to have more choices, and not to be forced into care because of bureaucratic hurdles or lack of support. They also push those who can contribute to do so, which could shore up the system’s finances.

But implementation is everything. If the rollout is smooth, waitlists shrink, and seniors find it easier to get the help they need without going broke, then these reforms could truly be a lifeline that lets more of us age with dignity where we belong. If not – if delays persist, costs deter people from seeking help, or families are left carrying an even heavier load – then the promise of ageing-in-place might prove to be a bit of a letdown, or at least a mixed blessing.

As one financial expert mused, “even with these proposed changes, [the ideal system] is still a way off.” We’re in a transition period. It’s hopeful and hectic all at once.

Aged care workers are doing their utmost on the ground, and they deserve credit – no reform is possible without their dedication. Yet they too need more hands on deck and better resources, whether in homes or facilities. It’s telling that crossbench MPs had to remind the government that “older Australians built this country” and deserve to age with dignity at home – a principle no one disagrees with, but one that’s easy to lose in the maze of policy details.

So, what do we make of it all? The new aged care laws will definitely change the game for many Australian seniors and their families. They bring a mix of encouragement and caution. On one side, there’s real optimism: more support to live at home, more funding for those who need it most, and a long overdue simplification of aged care services. On the other, there are valid concerns: potential service shortfalls, new fees nibbling at fixed incomes, and the question of whether we’re just papering over deeper cracks in the system (all while our housing woes rumble on).

For our senior readers, especially, this is personal. It’s about where and how you’ll live your later years – and who will be by your side. These reforms aim to tilt the balance toward home, community, and family. But we should be clear-eyed: supporting our elders at home will take effort from all of everyone – government, care providers, families, and the seniors themselves. It might mean adjusting expectations (maybe the family home will need to be sold someday, or maybe Junior will move into the spare room). It might mean embracing some new costs in return for better care. And it will certainly mean staying informed and engaged with the changes as they roll out.

What do you think – are we on the right track with these aged care reforms, or just kicking the can down the road on bigger issues?

READ MORE: Hard to Handle: How Everyday Products Are Failing Older Australians