Fears Australia will lose its war on fire ants, suffering the same fate as the US

By

ABC News

- Replies 0

They swarm, they sting, they're invasive, and they could be in your backyard soon.

Fire ants — named for their painful, burning sting — have relentlessly marched across south-east Queensland, steadily spreading north, south and west.

But in the United States, the imported "super pest" is more than an emerging nuisance.

It's a daily hazard, according to Mark Hoddle from the University of California's Applied Biological Control Research Centre.

"If the kids are out in the yard and they tread on one of these nests, the ants just boil out of it," Professor Hoddle said.

"You're not talking about one or two ants — there's hundreds to thousands."

As Australia battles to protect its beloved outdoor lifestyle, America's experience demonstrates the cost of losing this war.

In four cases, an ambulance was called, and 20 cases required hospitalisation.

In the US, it's estimated that more than 14 million people are stung each year.

Professor Hoddle has studied fire ants and how to kill them for three decades.

The insects gained a foothold in the US in the 1930s, after being imported among cargo from South America.

What followed was an insecticidal war, described by Professor Hoddle as "the Vietnam of entomology".

"It's ongoing and it will probably never be winnable with the technology we're currently using," he said.

"It just seems like an intractable problem."

Fire ants now infest more than 150 million hectares across 15 southern US states — an area larger than the Northern Territory.

In Australia, a similar pattern is unfolding, including rising opposition to the chemical treatments that experts say are vital to getting the pest under control.

"I'm seeing us lose this fight, and I have been at least for the last five years," she said.

Ms McKenna runs a fire ant Facebook group, with posts venting frustration over what many see as a broken system.

"People are disheartened — we feel like we're on our own battling this issue," she said.

"People are saying they're no longer bothering to report, which worries me."

Fire ant queens can fly up to 5 kilometres and lay about 2,000 eggs a day.

When a nest is disturbed, a pheromone is released, causing the ants to swarm and sting repeatedly.

Virginia Tech assistant professor of entomology Scotty Yang has studied fire ants in China, Taiwan, Australia and the US.

"When you get stung, you know how bad those fire ants are," he said.

Repeated multiple stings can cause severe allergic reactions, which can be fatal for those with underlying conditions.

"You're going to have pustules develop on your skin, it's going to be super itchy," Dr Yang said.

"You scratch them, you break the pustule, and there's a likelihood you're going to get the secondary infections."

A 2024 study published in the journal Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease found about a quarter of people stung developed an allergic reaction.

Dr Yang said humans were largely responsible for spreading fire ants beyond their natural barriers.

Early eradication attempts in the US drenched nests with pesticides like calcium cyanide, a toxic chemical that is now rarely used.

It killed the worker ants, but Dr Yang said it left the queen unharmed deep underground to rebuild the nest.

Colonies also hitched rides on the backs of trucks, planes and boats, transporting materials like soil, hay and turf.

They now infest around 850,000 hectares and have spread south of the border into the Tweed, Ballina and Byron Shires.

This month, fire ants were located at a coal mine near Mackay, central Queensland, and in a freight container at Perth.

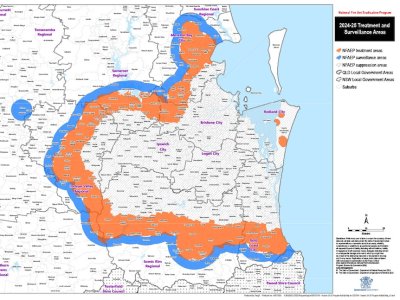

Under a $592 million program, an eradication zone stretches around south-east Queensland, where the National Fire Ant Eradication Program directly exterminates fire ant nests.

But within that area is the suppression zone, where landholders are required to manage nests themselves.

The goal is to treat the outer infested area and push inward, squeezing progressively towards the coast, wiping out ant populations as they go.

But the strategy has been criticised by residents, who fear populations in the suppression zone can spread unchecked, undermining the entire program.

"It's two to three hours of my day every day just complying with the necessary paperwork and treatment regime," he said.

Agricultural businesses like his must monitor their land regularly, apply bait or treatments on schedule, and submit detailed records for inspection.

But those rules do not apply to Mr Keleher's neighbours who live on rural residential blocks.

Instead, rural residents fall under a system that relies on self-reporting.

Mr Keleher fears it allows fire ant nests to go unnoticed and untreated.

"I'm directly looking into a neighbour's property and the pest population of ants there is endemic," he said.

"They're mating, they're flying onto my land, and I'm having to deal with the problem."

National Fire Ant Eradication Program general manager of operations Marni Manning said the density of fire ants had increased beyond what the community accepted.

She said efforts inside the suppression zone were being expanded, including aerial baiting.

"The more we weaken the population in the suppression area, the better eradication effectiveness will be," she said.

Crews have required police escorts to access some properties, and Southern Cross University recently came under fire for funding research by an anti-bait conspiracy theorist.

Professor Hoddle said similar dynamics derailed eradication efforts in the US.

"When there is not sufficient collective action for the public good, the programs collapse," he said.

"One or two selfish individuals that don't want to get on board with the program basically screw it up for everybody else."

Ms Manning said even if some landholders did not take action, eradication could still be achieved if the majority complied.

"We are trying really hard to explain to the community what the reality is if we don't eradicate," she said.

The chemicals prevent fire ant queens from producing mature worker ants, killing a colony over a couple of months.

Part of the program involves dropping baits from helicopters, prompting concerns from residents about the environmental impact.

But Invasive Species Council advocacy manager Reece Pianta said it was among the most environmentally friendly approaches over a large area.

"Native ants will forage this product and take it away, but the product is designed so the oil component of it is far more attractive to fire ants," he said.

A baiting program is underway to control fire ants spreading through the Northern Rivers region of NSW.

Ms Manning said the baiting program was critical to containing the pest.

"The last thing we want to do is have a situation where people are pouring a cocktail of chemicals onto their land just so they can actually sit outside," she said.

But the clock is ticking for the rest of Australia.

Outdoor events, camping trips, days at the beach and backyard barbecues all become complicated when you have to be on alert for aggressive, stinging ants.

Professor Hoddle said Australia had a narrow window to stop fire ants, but it could already be too late.

"With a lot of these programs, it often reaches a critical area of infestation where containment may or may not be possible," he said.

"Eradication now is almost certainly off the table because the area that's infested, it's just too big to manage."

But Professor Yang said eradication could be achieved if governments, landholders and everyday Australians acted fast.

"Australia is the last one standing, still fighting fire ants with the goal of eradication," he said.

"It's a big shock to me — I thought Australia had a really good chance to eradicate."

Ms Manning said the program was committed to the fight, with Queensland spending an additional $24 million over two years to bolster suppression.

"These super pests stand to inhabit at least 97 per cent of this country," she said.

"They're projected to cause more damage than cane toads, camels, foxes and feral pigs — all combined.

"We're not giving up on eradication."

Written by Dominic Cansdale and Chris Kimball, ABC News.

Fire ants — named for their painful, burning sting — have relentlessly marched across south-east Queensland, steadily spreading north, south and west.

But in the United States, the imported "super pest" is more than an emerging nuisance.

It's a daily hazard, according to Mark Hoddle from the University of California's Applied Biological Control Research Centre.

"If the kids are out in the yard and they tread on one of these nests, the ants just boil out of it," Professor Hoddle said.

"You're not talking about one or two ants — there's hundreds to thousands."

As Australia battles to protect its beloved outdoor lifestyle, America's experience demonstrates the cost of losing this war.

Going to war

The National Fire Ant Eradication Program received at least 463 reports of critical fire ant stings this year.In four cases, an ambulance was called, and 20 cases required hospitalisation.

In the US, it's estimated that more than 14 million people are stung each year.

Professor Hoddle has studied fire ants and how to kill them for three decades.

The insects gained a foothold in the US in the 1930s, after being imported among cargo from South America.

What followed was an insecticidal war, described by Professor Hoddle as "the Vietnam of entomology".

"It's ongoing and it will probably never be winnable with the technology we're currently using," he said.

"It just seems like an intractable problem."

Fire ants now infest more than 150 million hectares across 15 southern US states — an area larger than the Northern Territory.

In Australia, a similar pattern is unfolding, including rising opposition to the chemical treatments that experts say are vital to getting the pest under control.

Weapons of choice

On Queensland's Scenic Rim, Kirsty McKenna has seen the number of fire ant nests at her property spread from one to thousands."I'm seeing us lose this fight, and I have been at least for the last five years," she said.

Ms McKenna runs a fire ant Facebook group, with posts venting frustration over what many see as a broken system.

"People are disheartened — we feel like we're on our own battling this issue," she said.

"People are saying they're no longer bothering to report, which worries me."

Fire ant queens can fly up to 5 kilometres and lay about 2,000 eggs a day.

When a nest is disturbed, a pheromone is released, causing the ants to swarm and sting repeatedly.

Virginia Tech assistant professor of entomology Scotty Yang has studied fire ants in China, Taiwan, Australia and the US.

"When you get stung, you know how bad those fire ants are," he said.

Repeated multiple stings can cause severe allergic reactions, which can be fatal for those with underlying conditions.

"You're going to have pustules develop on your skin, it's going to be super itchy," Dr Yang said.

"You scratch them, you break the pustule, and there's a likelihood you're going to get the secondary infections."

A 2024 study published in the journal Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease found about a quarter of people stung developed an allergic reaction.

Dr Yang said humans were largely responsible for spreading fire ants beyond their natural barriers.

Early eradication attempts in the US drenched nests with pesticides like calcium cyanide, a toxic chemical that is now rarely used.

It killed the worker ants, but Dr Yang said it left the queen unharmed deep underground to rebuild the nest.

Colonies also hitched rides on the backs of trucks, planes and boats, transporting materials like soil, hay and turf.

Queensland's battle plan

Fire ants were first detected in Brisbane in 2001 but have surged across south-east Queensland in recent years.They now infest around 850,000 hectares and have spread south of the border into the Tweed, Ballina and Byron Shires.

This month, fire ants were located at a coal mine near Mackay, central Queensland, and in a freight container at Perth.

Under a $592 million program, an eradication zone stretches around south-east Queensland, where the National Fire Ant Eradication Program directly exterminates fire ant nests.

But within that area is the suppression zone, where landholders are required to manage nests themselves.

The goal is to treat the outer infested area and push inward, squeezing progressively towards the coast, wiping out ant populations as they go.

But the strategy has been criticised by residents, who fear populations in the suppression zone can spread unchecked, undermining the entire program.

Rallying the troops

Inside the suppression zone, turf farmer John Keleher has spent $1.5 million over the past two years managing fire ants on his property near Beaudesert."It's two to three hours of my day every day just complying with the necessary paperwork and treatment regime," he said.

Agricultural businesses like his must monitor their land regularly, apply bait or treatments on schedule, and submit detailed records for inspection.

But those rules do not apply to Mr Keleher's neighbours who live on rural residential blocks.

Instead, rural residents fall under a system that relies on self-reporting.

Mr Keleher fears it allows fire ant nests to go unnoticed and untreated.

"I'm directly looking into a neighbour's property and the pest population of ants there is endemic," he said.

"They're mating, they're flying onto my land, and I'm having to deal with the problem."

National Fire Ant Eradication Program general manager of operations Marni Manning said the density of fire ants had increased beyond what the community accepted.

She said efforts inside the suppression zone were being expanded, including aerial baiting.

"The more we weaken the population in the suppression area, the better eradication effectiveness will be," she said.

Battlelines drawn

Although landholders are legally required to allow biosecurity officers onto their properties, there has been resistance, which Ms Manning believes is fed in part by misinformation.Crews have required police escorts to access some properties, and Southern Cross University recently came under fire for funding research by an anti-bait conspiracy theorist.

Professor Hoddle said similar dynamics derailed eradication efforts in the US.

"When there is not sufficient collective action for the public good, the programs collapse," he said.

"One or two selfish individuals that don't want to get on board with the program basically screw it up for everybody else."

Ms Manning said even if some landholders did not take action, eradication could still be achieved if the majority complied.

"We are trying really hard to explain to the community what the reality is if we don't eradicate," she said.

Aerial attack

The National Fire Ant Eradication Program uses corn grit baits soaked in soybean oil that contain pyriproxyfen or methoprene, both insect growth regulators approved by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority.The chemicals prevent fire ant queens from producing mature worker ants, killing a colony over a couple of months.

Part of the program involves dropping baits from helicopters, prompting concerns from residents about the environmental impact.

But Invasive Species Council advocacy manager Reece Pianta said it was among the most environmentally friendly approaches over a large area.

"Native ants will forage this product and take it away, but the product is designed so the oil component of it is far more attractive to fire ants," he said.

A baiting program is underway to control fire ants spreading through the Northern Rivers region of NSW.

Ms Manning said the baiting program was critical to containing the pest.

"The last thing we want to do is have a situation where people are pouring a cocktail of chemicals onto their land just so they can actually sit outside," she said.

But the clock is ticking for the rest of Australia.

D-day approaches

Beyond the medical, environmental and economic cost of fire ants is the risk to outdoor lifestyles.Outdoor events, camping trips, days at the beach and backyard barbecues all become complicated when you have to be on alert for aggressive, stinging ants.

Professor Hoddle said Australia had a narrow window to stop fire ants, but it could already be too late.

"With a lot of these programs, it often reaches a critical area of infestation where containment may or may not be possible," he said.

"Eradication now is almost certainly off the table because the area that's infested, it's just too big to manage."

But Professor Yang said eradication could be achieved if governments, landholders and everyday Australians acted fast.

"Australia is the last one standing, still fighting fire ants with the goal of eradication," he said.

"It's a big shock to me — I thought Australia had a really good chance to eradicate."

Ms Manning said the program was committed to the fight, with Queensland spending an additional $24 million over two years to bolster suppression.

"These super pests stand to inhabit at least 97 per cent of this country," she said.

"They're projected to cause more damage than cane toads, camels, foxes and feral pigs — all combined.

"We're not giving up on eradication."

Written by Dominic Cansdale and Chris Kimball, ABC News.