Even if Qantas is fined hundreds of millions it is likely to continue to take us for granted

- Replies 0

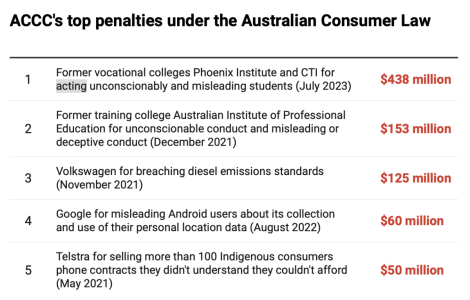

As Qantas faces up to tough questioning from a Senate committee and a claim from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) for as much as A$600 millionfor allegedly selling tickets on more than 8,000 “ghost flights” it had already cancelled, its customers might be thinking things are about to get better.

But there are reasons to think they won’t. At the heart of both the ACCC’s lawsuit, and the airline’s separate refusal to quickly refund hundreds of millions of dollars worth of credits for flights cancelled during COVID, lies the indifference to customers typical of a duopolistic market.

Qantas does face competition on international routes, although the government’s action in denying Qatar Airways extra landing rights has constrained that competition.

But, with only one exception – Virgin – it faces very little competition within Australia, given the limited offerings by airlines such as Rex and Bonza.

On Wednesday former ACCC Chair Rod Sims told the Senate inquiry into air service agreements Qantas was able to use its leading market position to charge higher prices than it would otherwise have been able to.

One could put it more generally: Qantas had the power to treat customers worse than it would otherwise have been able to.

Under the law, where liability for “misleading or deceptive conduct” is concerned, the reasons for the conduct don’t matter, meaning all that is likely to matter is whether the commission’s claims about Qantas’s conduct are true.

Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law simply says:

While the ticket contracts may have included disclaimers, these would be unlikely to have force in the face of Section 18. The law does not permit contractual language to exclude liability for contraventions of this provision.

A disclaimer can be relevant to the factual question of whether a party was misled but, given 98% of online consumer contracts are unread, it’s unlikely Qantas would be able to rely on disclaimers to claim customers weren’t misled.

Even if the commission is successful in getting the Federal Court to award a penalty amounting to hundreds of millions, such a fine is likely to be manageable for Qantas given its $1.7 billion2022-23 profit.

They also passed up the opportunity to provide the committee with a written statement addressing the formal topic of its inquiry which was the impact of government decisions about landing rights on competition in the aviation industry and the cost of living pressures on Australian families and businesses.

Pressed on whether Qantas would publish a redacted version of its representations to the government about foreign airlines’ bids for landing rights, Hudson declined, although she said Qantas would provide them in confidence.

Goyder told the hearing Qantas had “genuine contrition for where we are at” but had “sound commercial reasons” for many of the decisions it took during the years since the outbreak of COVID, including what the High Court subsequently found was an illegal decision to sack 1,700 ground staff.

The current rules allow incumbent airlines such as Qantas to apply for more slots at airports such as Sydney than they will require, so long as they use them 80% of the time.

In a report to the government in 2021 former Productivity Commission chief Peter Harris recommended overhauling the system at Sydney Airport to make it easier for new entrants to get slots.

Among the recommendations was an independent audit of cancellations by a “reputable, unconflicted auditor”.

The government has yet to respond to the report, although when releasing the government’s aviation green paper earlier this month, Transport Minister Catherine King indicated she soon would.

Implementing needed reforms to free up slots at key airports would help to promote better consumer outcomes. However, profound change in Australian air travel seems unlikely for the foreseeable future.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Mel Marquis, Deputy Associate Dean and Senior Lecturer in Law, Monash University, Neerav Srivastava, PhD Candidate and Teaching Associate, Monash University

But there are reasons to think they won’t. At the heart of both the ACCC’s lawsuit, and the airline’s separate refusal to quickly refund hundreds of millions of dollars worth of credits for flights cancelled during COVID, lies the indifference to customers typical of a duopolistic market.

Qantas does face competition on international routes, although the government’s action in denying Qatar Airways extra landing rights has constrained that competition.

But, with only one exception – Virgin – it faces very little competition within Australia, given the limited offerings by airlines such as Rex and Bonza.

On Wednesday former ACCC Chair Rod Sims told the Senate inquiry into air service agreements Qantas was able to use its leading market position to charge higher prices than it would otherwise have been able to.

One could put it more generally: Qantas had the power to treat customers worse than it would otherwise have been able to.

What the ACCC alleges

The ACCC alleges Qantas engaged in false, misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of the Australian Consumer Law in 2022 by selling tickets for flights that had already been cancelled, and by falsely representing to consumers who already had tickets that their flights had not been cancelled.Under the law, where liability for “misleading or deceptive conduct” is concerned, the reasons for the conduct don’t matter, meaning all that is likely to matter is whether the commission’s claims about Qantas’s conduct are true.

Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law simply says:

For online bookings, the commission is suggesting Qantas may have made several misleading representations, including indicating flights were available when they were not, confirming bookings for flights that were not available, and displaying unavailable flights on customers’ “manage booking” pages.a person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

While the ticket contracts may have included disclaimers, these would be unlikely to have force in the face of Section 18. The law does not permit contractual language to exclude liability for contraventions of this provision.

A disclaimer can be relevant to the factual question of whether a party was misled but, given 98% of online consumer contracts are unread, it’s unlikely Qantas would be able to rely on disclaimers to claim customers weren’t misled.

Even if the commission is successful in getting the Federal Court to award a penalty amounting to hundreds of millions, such a fine is likely to be manageable for Qantas given its $1.7 billion2022-23 profit.

Qantas chair Richard Goyder at the Senate hearing. Lukas Coch/AAP

Qantas ill-prepared for questions

At Wednesday’s Senate hearing Qantas chief executive Vanessa Hudson and Chairman Richard Goyder were not prepared to answer several questions, asking for them to be put on notice.They also passed up the opportunity to provide the committee with a written statement addressing the formal topic of its inquiry which was the impact of government decisions about landing rights on competition in the aviation industry and the cost of living pressures on Australian families and businesses.

Pressed on whether Qantas would publish a redacted version of its representations to the government about foreign airlines’ bids for landing rights, Hudson declined, although she said Qantas would provide them in confidence.

Goyder told the hearing Qantas had “genuine contrition for where we are at” but had “sound commercial reasons” for many of the decisions it took during the years since the outbreak of COVID, including what the High Court subsequently found was an illegal decision to sack 1,700 ground staff.

What matters to Qantas is slots

While there is little that can be done to make Qantas more responsive to its customers while it dominates the domestic aviation market, freeing up landing slots at airports would help loosen that dominance.The current rules allow incumbent airlines such as Qantas to apply for more slots at airports such as Sydney than they will require, so long as they use them 80% of the time.

In a report to the government in 2021 former Productivity Commission chief Peter Harris recommended overhauling the system at Sydney Airport to make it easier for new entrants to get slots.

Among the recommendations was an independent audit of cancellations by a “reputable, unconflicted auditor”.

The government has yet to respond to the report, although when releasing the government’s aviation green paper earlier this month, Transport Minister Catherine King indicated she soon would.

Implementing needed reforms to free up slots at key airports would help to promote better consumer outcomes. However, profound change in Australian air travel seems unlikely for the foreseeable future.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Mel Marquis, Deputy Associate Dean and Senior Lecturer in Law, Monash University, Neerav Srivastava, PhD Candidate and Teaching Associate, Monash University