Are bigger super funds better? Actually no, despite what the industry is doing

- Replies 0

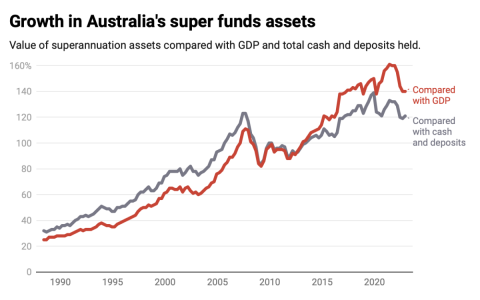

Australia’s superannuation funds are getting bigger – and fewer. There were close to 400 funds in 2010. With mergers, it’s now closer to 120. By 2025, according to industry executives surveyed last year, there will be fewer than 50.

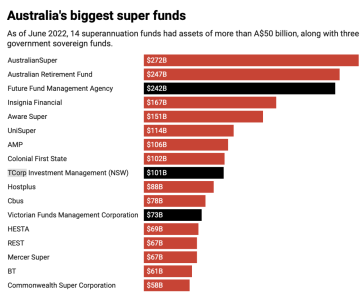

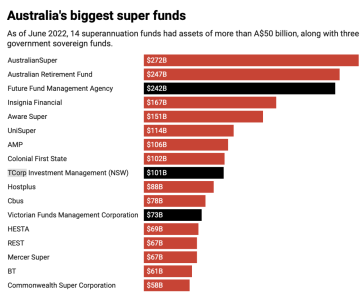

The portfolios of the two biggest super funds, AustralianSuper and Australian Retirement Trust, are bigger than even the federal government’s Future Fund Management Agency, which oversees the A$194 billion Future Fund and several other funds worth a total $242 billion.

Underpinning this consolidation is the idea that larger scale is beneficial for superannuation fund members. But that’s not necessarily true. A bigger fund is no guarantee of better returns.

I’ve examined the issue of fund scale with Scott Lawrence, an investment manager with 35 year’s industry experience. Together we’ve written a report for the Conexus Institute, an independent research centre focused on superannuation issues.

Our conclusion: funds, large and small alike, succeed or fail depending on how well they formulate and execute their strategies.

For example, UniSuper (the higher education industry fund) manages 70% of assets in-house. AustralianSuper, with more than double UniSuper’s assets, manages 53% of assets in-house.

This can be cheaper than paying fees as a percentage of assets to these external providers. It offers more control as the super fund can decide the assets in which they invest, rather than leaving the decision to someone else.

But fund members will only benefit if the internal team makes investment decisions that are as good as the service they are replacing. For this reason, there is no reliable correlation between performance and degree of in-house management.

For example, AustralianSuper owns 20.5% of WestConnex, Australia’s biggest infracture project, having contributed $4.2 billion to the consortium that is building the mostly underground toll-road system linking western Sydney motorways.

Opportunities like this are easier to access by large funds, and can help to diversify their portfolios.

But such direct investment is costlier than buying shares and bonds. This limits the potential for fee reductions.

For members to benefit, these investments must deliver attractive returns. This requires a fund developing capability in what are specialised markets. Size alone won’t deliver on its own.

Scale can reduce fees, by spreading the fund’s fixed costs over a larger member base.

Our review of the research literature confirms there are solid reasons to expect administration costs to reduce with size, as well as in-house management reducing investment costs.

Economies of scope involve an organisation being able to improve or increase services, say by investing in better systems and more staff.

But investing in better systems also brings potential pitfalls. Big visionary projects tend to run over time and over budget, and sometimes fail.

An example is the disastrous attempts of five industry funds (AustralianSuper, Cbus Super, HESTA, Hostplus and MTAA Super) to develop a shared administration platform, called Superpartners. It was meant to cost $70 million, but development costs blew out to $250 million before they gave up.

The risk is they need to accept some assets offering low returns to do so. They can also outgrow some market segments, such as owning shares in smaller companies.

Large organisations are typically more complex, more bureaucratic and less flexible. They can find it difficult to coordinate staff to work towards a common purpose. These elements may create dysfunction if not managed.

This may explain why, despite the potential increased scope of their offerings, surveys suggest large funds tend to deliver less personalised service.

So the idea “bigger is better” is not necessarily true. Large size is not an automatic win. Whether the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and challenges ultimately depends on fund trustees and management doing their jobs well so that members benefit.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Geoff Warren, Associate Professor, College of Business and Economics, Australian National University

The portfolios of the two biggest super funds, AustralianSuper and Australian Retirement Trust, are bigger than even the federal government’s Future Fund Management Agency, which oversees the A$194 billion Future Fund and several other funds worth a total $242 billion.

Superannuation funds are shown in red, other funds in black.

Chart: The Conversation Source: APRA and fund annual reports Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Chart: The Conversation Source: APRA and fund annual reports Get the data Created with Datawrapper

Underpinning this consolidation is the idea that larger scale is beneficial for superannuation fund members. But that’s not necessarily true. A bigger fund is no guarantee of better returns.

I’ve examined the issue of fund scale with Scott Lawrence, an investment manager with 35 year’s industry experience. Together we’ve written a report for the Conexus Institute, an independent research centre focused on superannuation issues.

Our conclusion: funds, large and small alike, succeed or fail depending on how well they formulate and execute their strategies.

Managing assets in-house

The first potential benefit of bigger size is that funds can manage assets using their own dedicated investment professionals, rather than outsourcing everything to external investment managers to invest on their behalf.For example, UniSuper (the higher education industry fund) manages 70% of assets in-house. AustralianSuper, with more than double UniSuper’s assets, manages 53% of assets in-house.

This can be cheaper than paying fees as a percentage of assets to these external providers. It offers more control as the super fund can decide the assets in which they invest, rather than leaving the decision to someone else.

But fund members will only benefit if the internal team makes investment decisions that are as good as the service they are replacing. For this reason, there is no reliable correlation between performance and degree of in-house management.

Investing in big-ticket items

The second potential benefit is it becomes more possible to become successful direct investors in “big ticket” assets such as infrastructure and property, instead of just focusing on shares and other assets traded on stock exchanges.For example, AustralianSuper owns 20.5% of WestConnex, Australia’s biggest infracture project, having contributed $4.2 billion to the consortium that is building the mostly underground toll-road system linking western Sydney motorways.

AustralianSuper is part of consortium led by Transurban that paid NSW government $9 billion in 2018 for 51% ownership of WestConnex. Dan Himbrechts

Opportunities like this are easier to access by large funds, and can help to diversify their portfolios.

But such direct investment is costlier than buying shares and bonds. This limits the potential for fee reductions.

For members to benefit, these investments must deliver attractive returns. This requires a fund developing capability in what are specialised markets. Size alone won’t deliver on its own.

Economies of scale and scope

The third potential benefit is that size brings economies of scale and scope.Scale can reduce fees, by spreading the fund’s fixed costs over a larger member base.

Our review of the research literature confirms there are solid reasons to expect administration costs to reduce with size, as well as in-house management reducing investment costs.

Economies of scope involve an organisation being able to improve or increase services, say by investing in better systems and more staff.

But investing in better systems also brings potential pitfalls. Big visionary projects tend to run over time and over budget, and sometimes fail.

An example is the disastrous attempts of five industry funds (AustralianSuper, Cbus Super, HESTA, Hostplus and MTAA Super) to develop a shared administration platform, called Superpartners. It was meant to cost $70 million, but development costs blew out to $250 million before they gave up.

Size brings its own challenges

Large funds also face some unique challenges. Because they have more money to invest, they have more work to do in finding sufficient attractive assets to buy.The risk is they need to accept some assets offering low returns to do so. They can also outgrow some market segments, such as owning shares in smaller companies.

Large organisations are typically more complex, more bureaucratic and less flexible. They can find it difficult to coordinate staff to work towards a common purpose. These elements may create dysfunction if not managed.

This may explain why, despite the potential increased scope of their offerings, surveys suggest large funds tend to deliver less personalised service.

So the idea “bigger is better” is not necessarily true. Large size is not an automatic win. Whether the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and challenges ultimately depends on fund trustees and management doing their jobs well so that members benefit.

This article was first published on The Conversation, and was written by Geoff Warren, Associate Professor, College of Business and Economics, Australian National University